Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Segmentation and the Principles of Object Perception

segmentation

using featural information

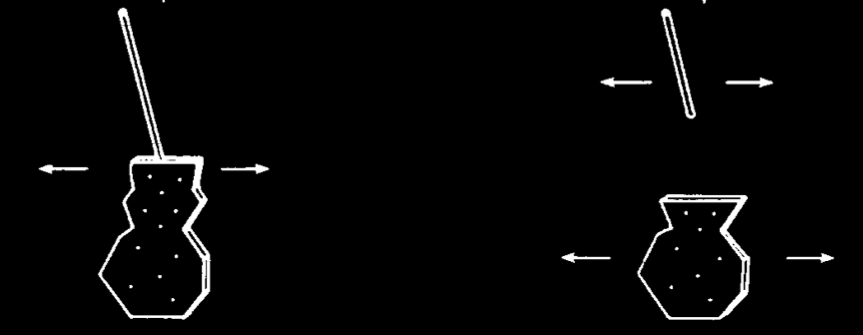

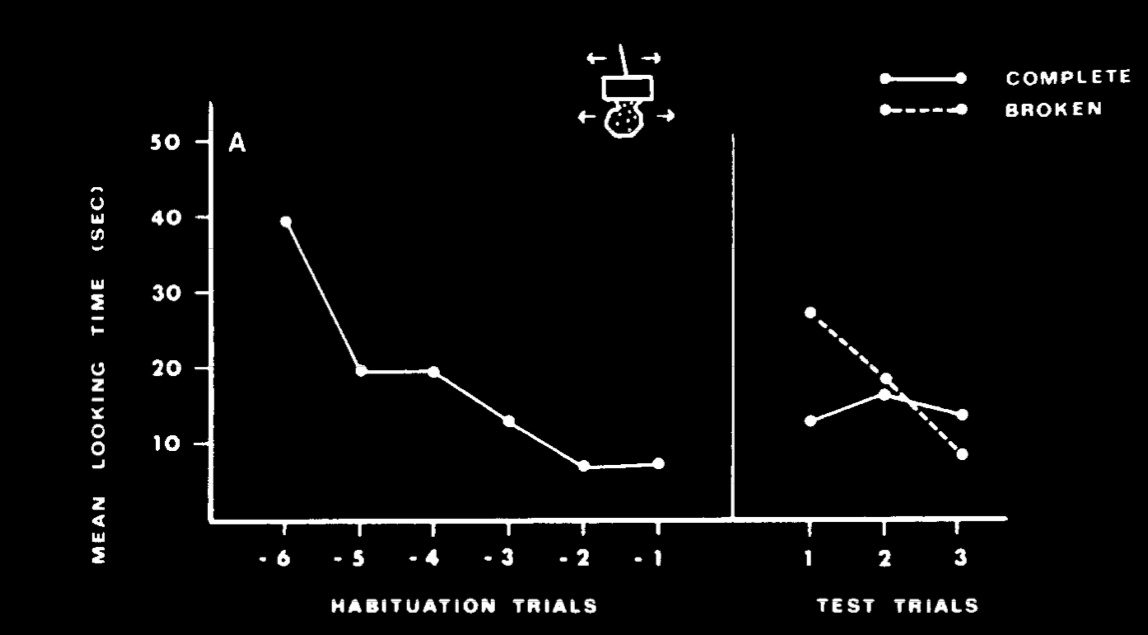

Needham (1998)

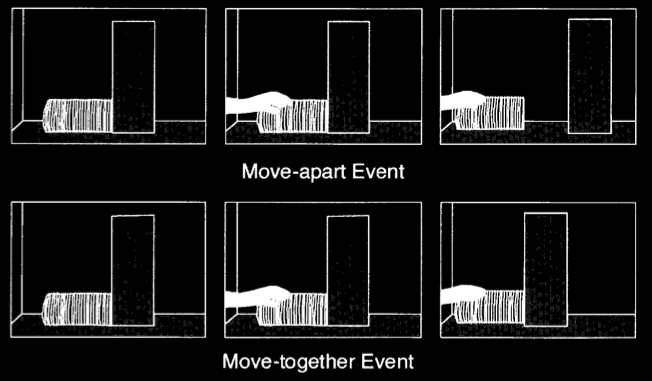

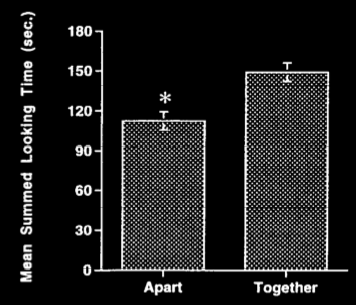

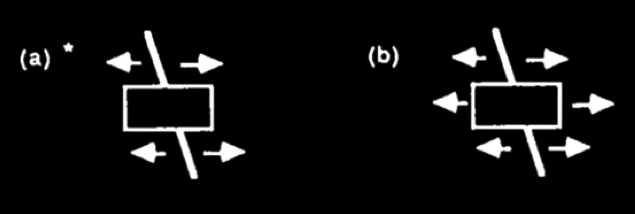

Needham (1998, figure 4)

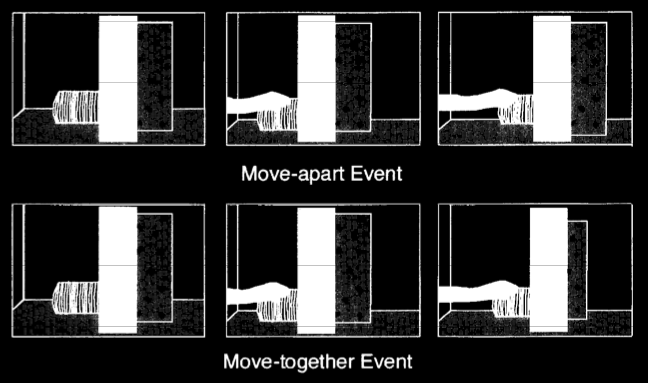

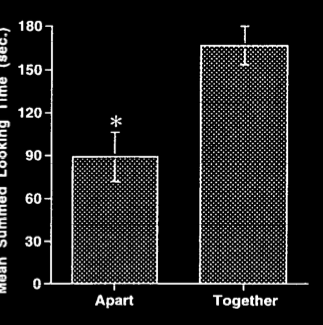

Needham (1998, figure 6)

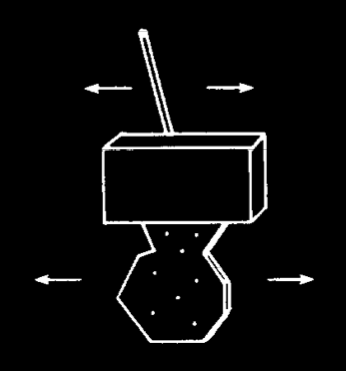

Needham (1998, figure 7)

Could it all be features?

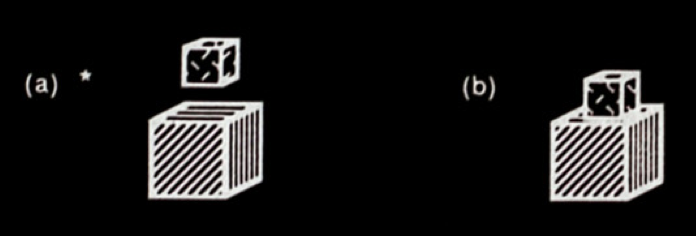

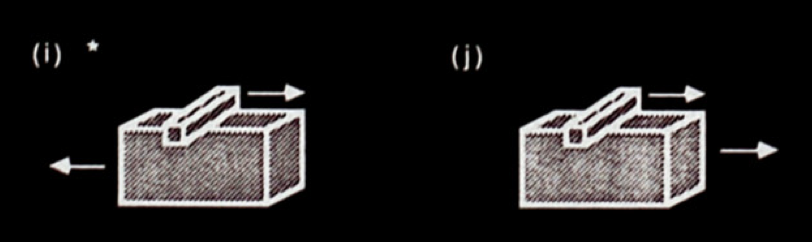

Spelke (1990, figure 2)

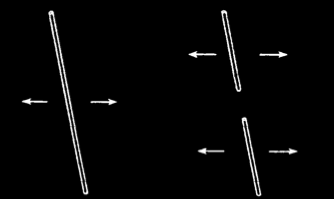

Kellman & Spelke (1983, figure 3)

Kellman & Spelke (1983, figure 4)

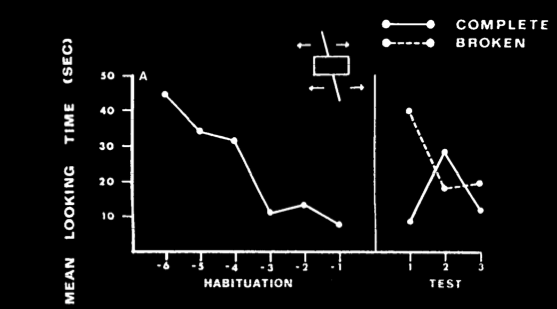

Kellman & Spelke (1983, figure 13)

Kellman & Spelke (1983, figure 13)

Kellman & Spelke (1983, figure 14)

If not by features, then how? Principles!

Kellman & Spelke (1983, figure 13)

rigidity—‘objects are interpreted as moving rigidly if such an interpretation exists’

cohesion:

‘two surface points lie on the same object only if the points are linked by a path of connected surface points’

(Spelke 1990)

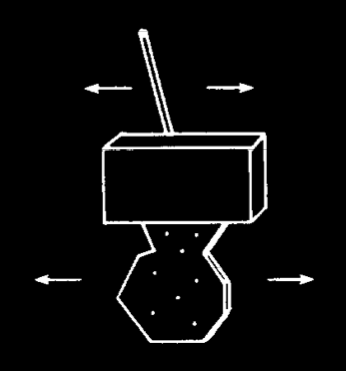

Spelke (1990, figure 4)

Principles of Object Perception

- cohesion—‘two surface points lie on the same object only if the points are linked by a path of connected surface points’

- boundedness—‘two surface points lie on distinct objects only if no path of connected surface points links them’

- rigidity—‘objects are interpreted as moving rigidly if such an interpretation exists’

- no action at a distance—‘separated objects are interpreted as moving independently of one another if such an interpretation exists’

(Spelke 1990)

\begin{enumerate}

\item We (as perceivers) start with a cross-modal representation of three-dimensional perceptual features which includes their locations and trajectories.

\item Our task is to get from these representations of features to representations of objects.

\item \emph{Descriptive component} We do this as if in accordance with certain principles (cohesion, boundedness, rigidity, and no action at a distance).

\item \emph{Explanatory component} We acquire representations of objects because we apply the principles to representations of features and draw appropriate inferences.

\end{enumerate}

Marr & Chomsky

the simple view

‘objects are conceived: Humans come to know about an object’s unity, boundaries, and persistence in ways like those by which we come to know about its material composition or its market value’

Spelke (1988, p. 198)