Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Permanence

Three requirements

- segment objects

- represent objects as persisting (‘permanence’)

- track objects’ interactions

Object permanence:

the ability to know things about, or represent, objects you aren't currently perceiving.

‘young infants’ physical world, like adults’, includes both visible [perceived] and hidden objects’

(Wang et al 2004, p. 194)

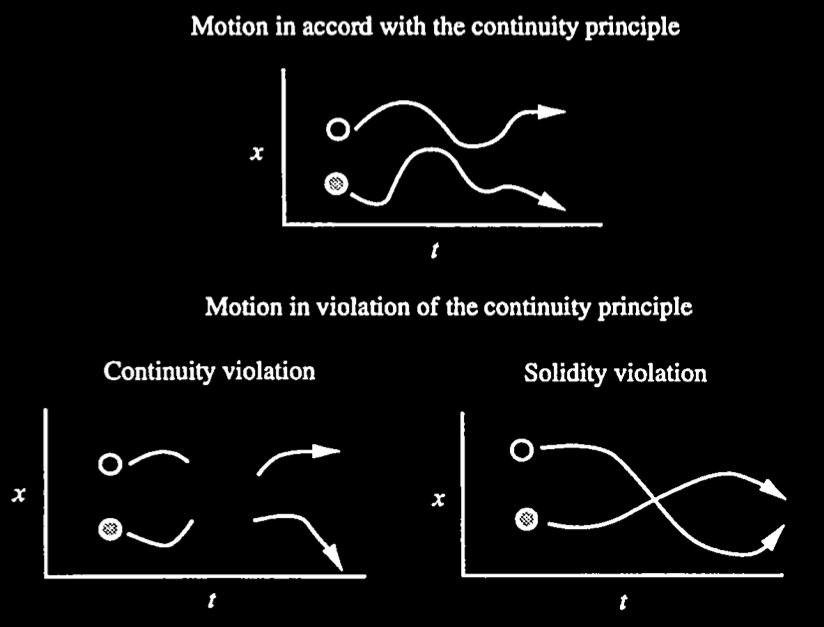

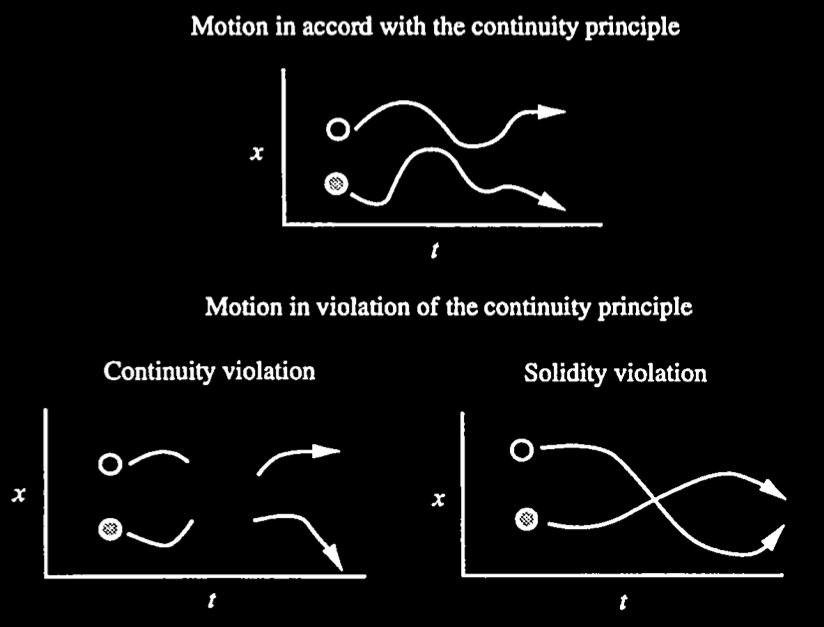

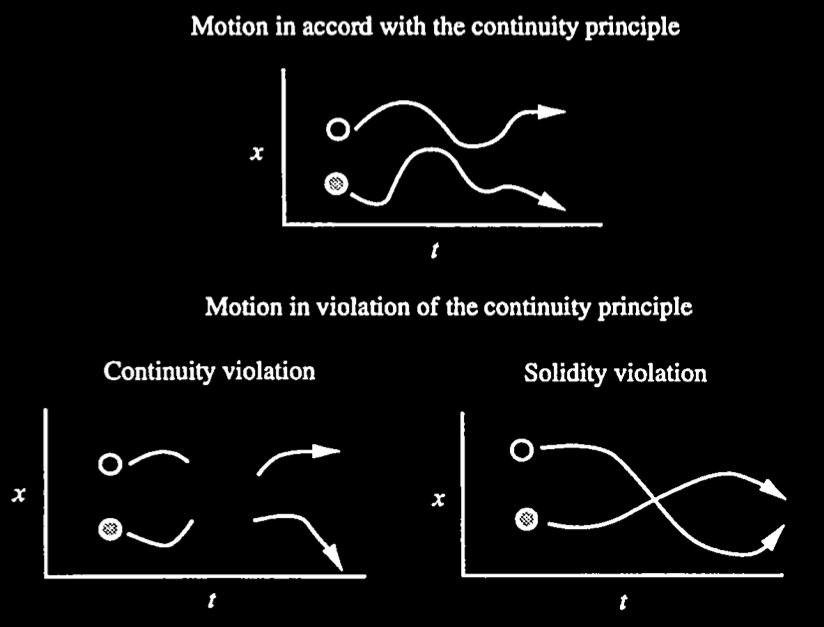

principle of continuity---

an object traces exactly one connected path over space and time

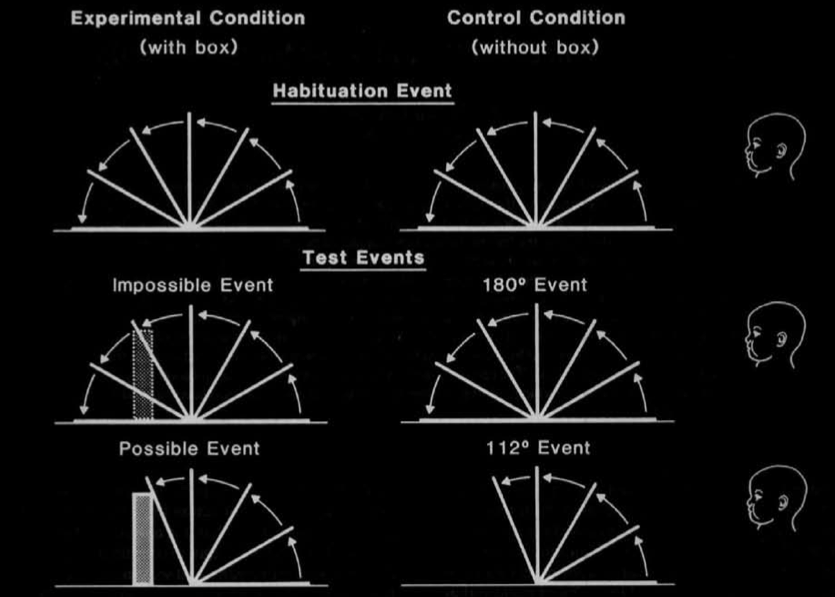

Spelke et al (1995, figure 1)

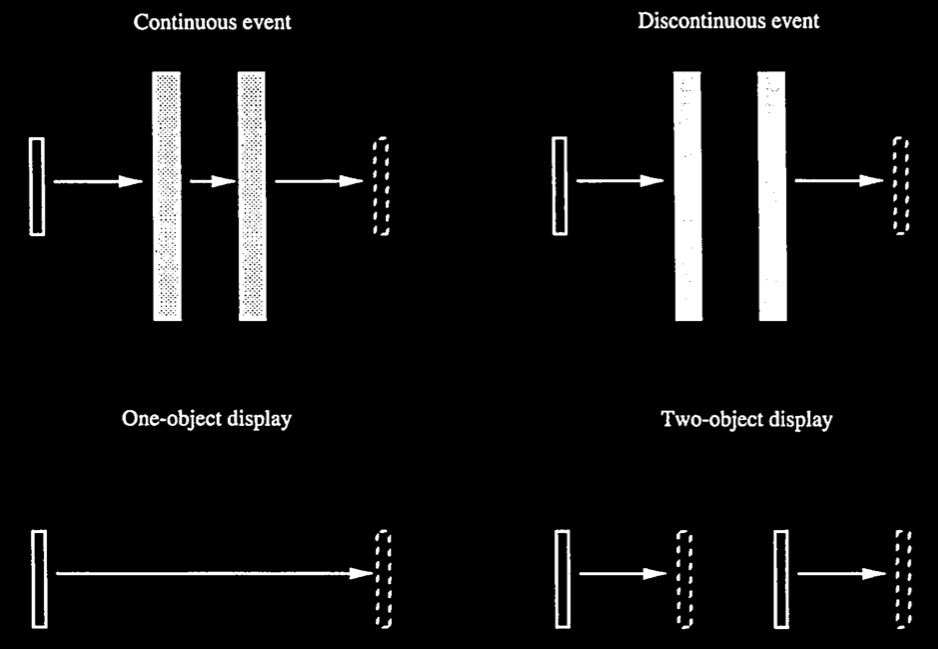

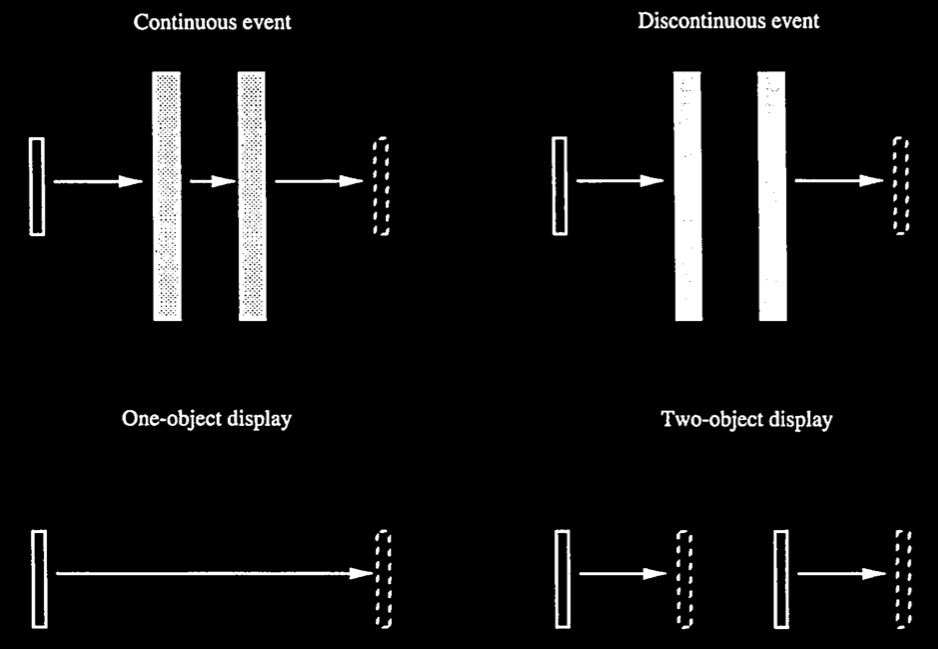

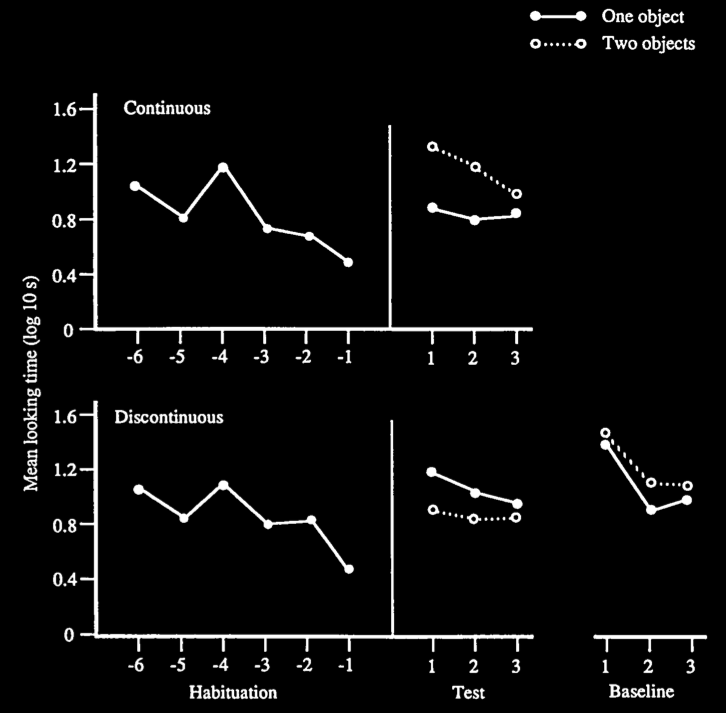

Spelke et al (1995, figure 2)

Spelke et al (1995, figure 3)

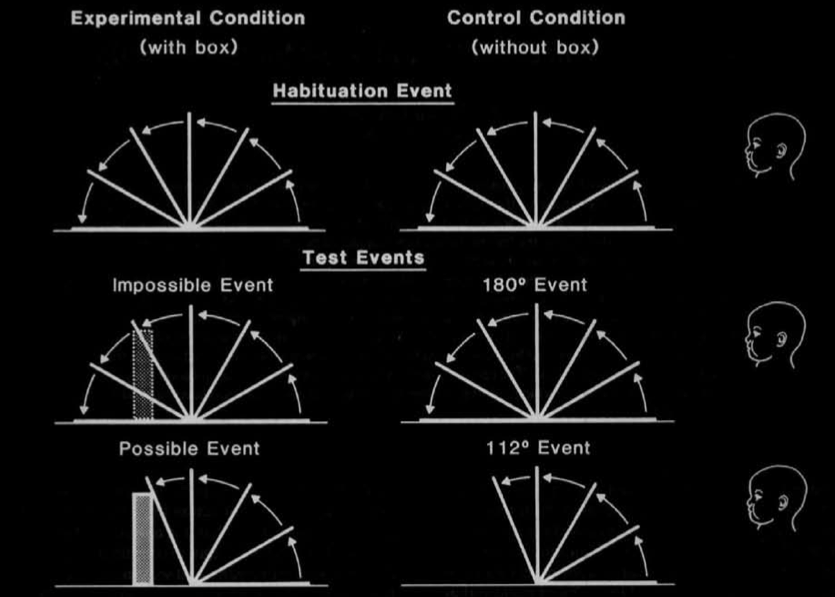

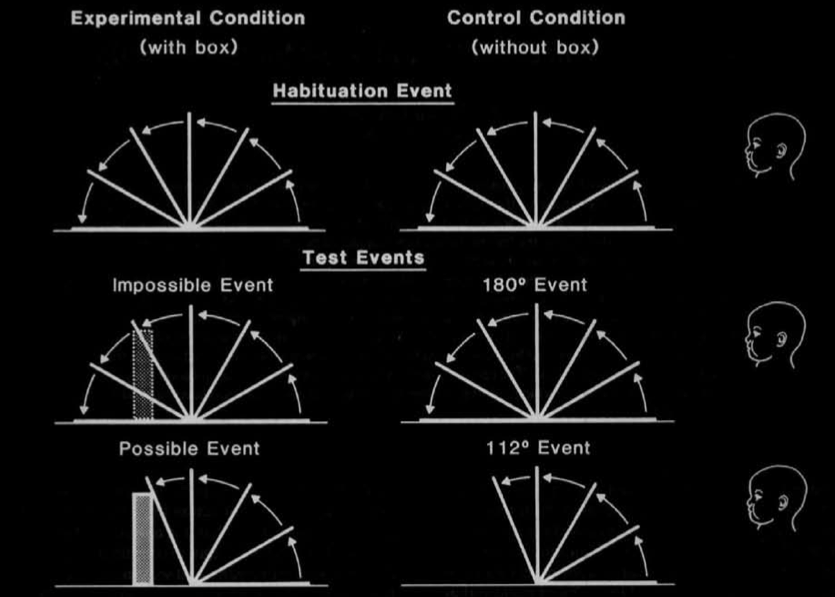

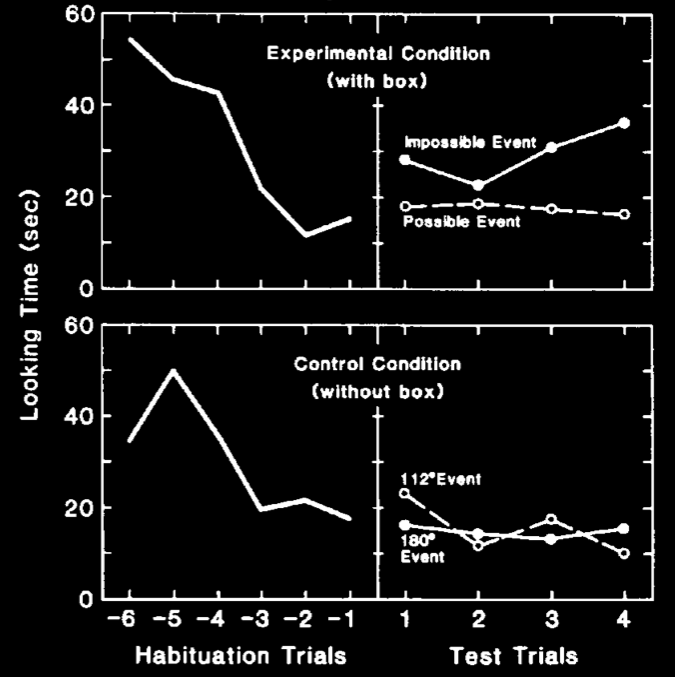

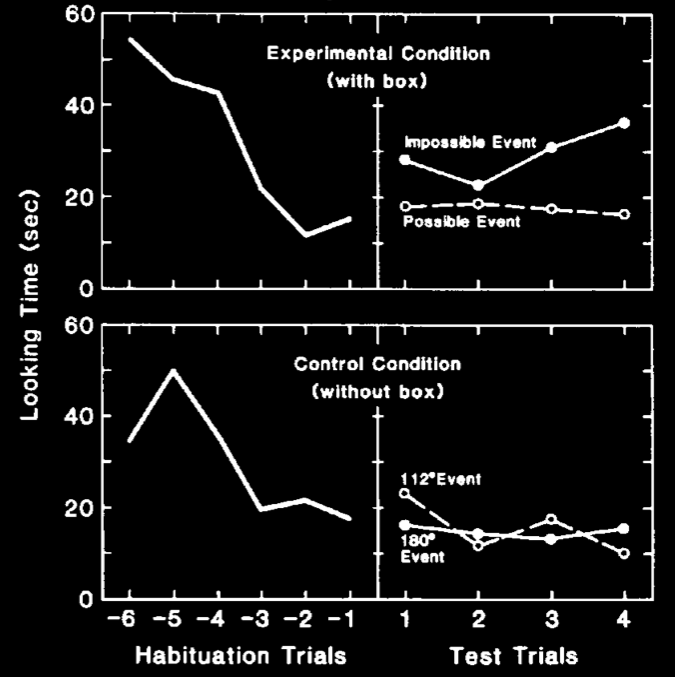

Baillargeon et al (1987, figure 1)

source: Baillargeon et al (1987, figure 2)

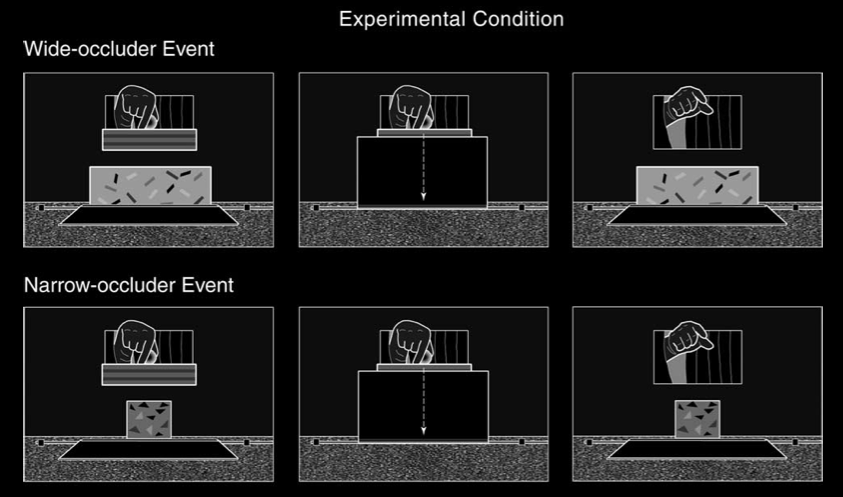

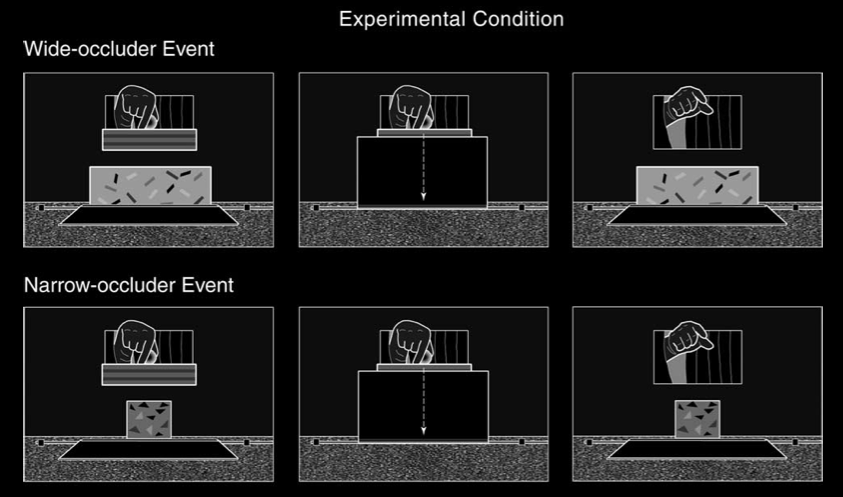

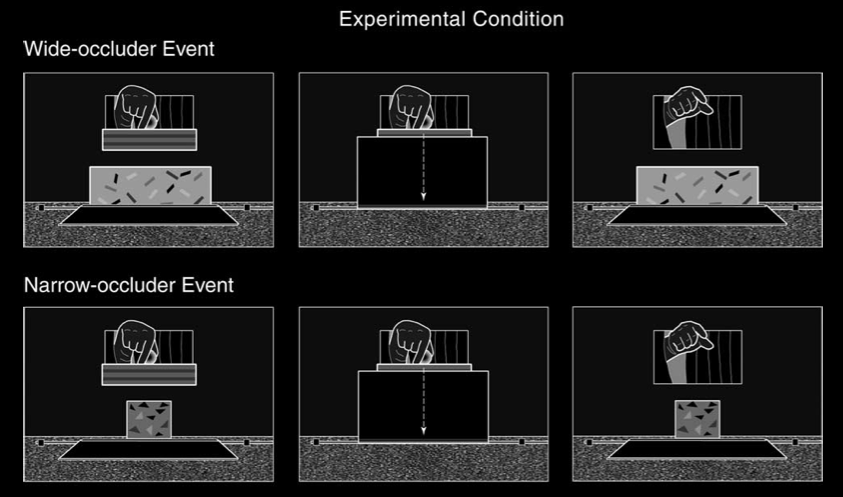

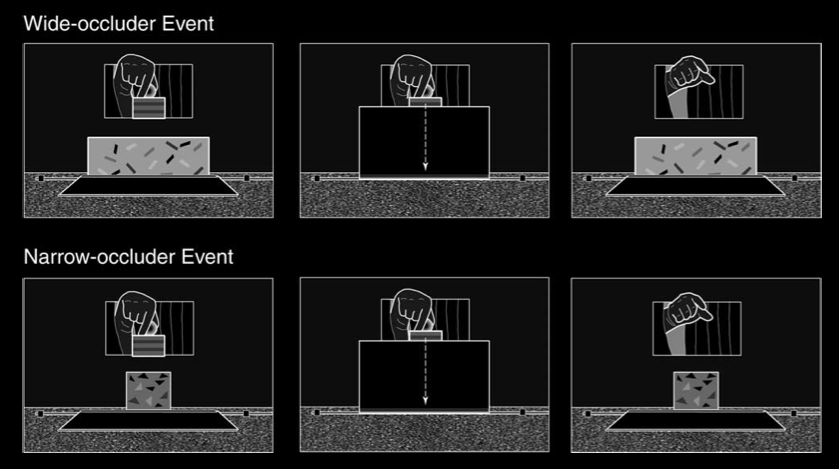

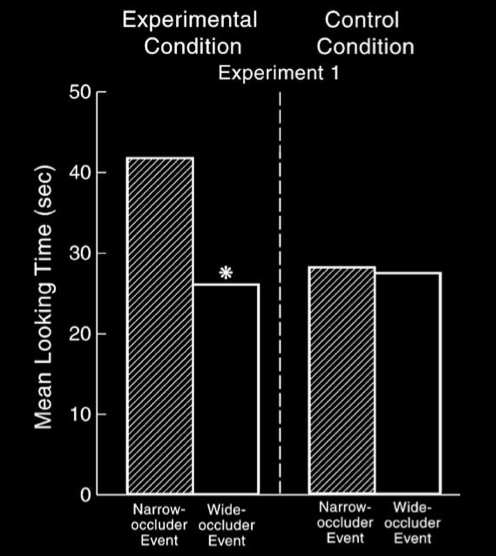

Wang et al (2004, figure 1)

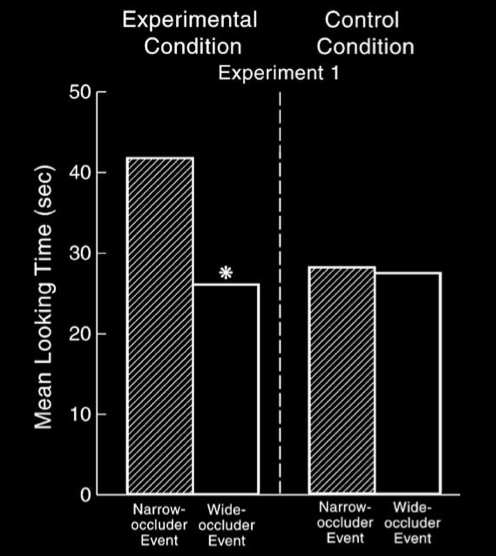

Wang et al (2004, figure 2)

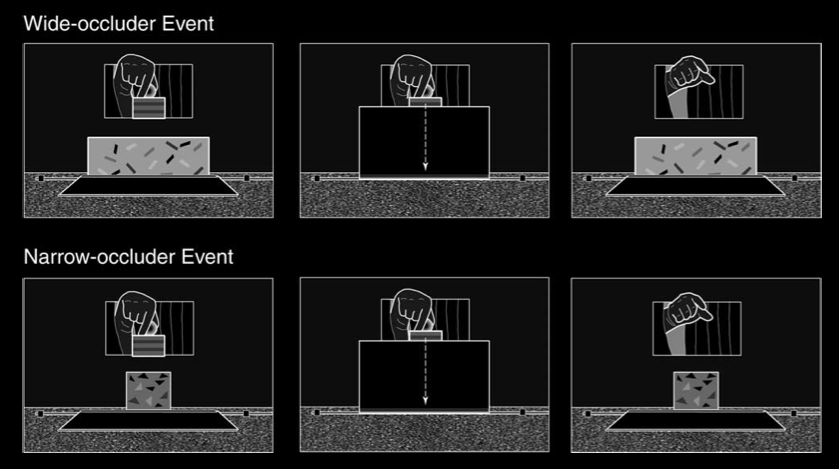

Control condition

Wang et al (2004, figure 1)

Experimental condition

Wang et al (2004, figure 1)

Control condition

Wang et al (2004, figure 1)

Wang et al (2004, figure 2)

methods

habituation vs violation-of-expectation

‘evidence that infants look reliably longer at the unexpected than at the expected event is taken to indicate that they

‘(1) possess the expectation under investigation;

‘(2) detect the violation in the unexpected event; and

‘(3) are surprised by this violation.’

‘The term surprise is used here simply as a short-hand descriptor, to denote a state of heightened attention or interest caused by an expectation violation.’

(Wang et al 2004, p. 168)

‘To make sense of such results [i.e. the results from violation-of-expectation tasks], we … must assume that infants, like older learners, formulate … hypotheses about physical events and revise and elaborate these hypotheses in light of additional input.’

(Aguiar and Baillargeon 2002: 329).

principles of object perception

{

segmentation

permanence

... (?)

Object permanence is found in nonhuman animals including

- monkeys (Santos et al 2006)

\item monkeys \citep{santos:2006_cotton-top}

- lemurs (Deppe et al 2009)

\item lemurs \citep{deppe:2009_object}

- crows (Hoffmann et al 2011)

\item crows \citep{hoffmann:2011_ontogeny}

- dogs and wolves(Fiset et al 2013)

\item dogs and wolves \citep{fiset:2013_object}

- cats (Triana & Pasnak 1981)

\item cats \citep{triana:1981_object}

- chicks (Chiandetti et al 2011)

\item chicks \citep{chiandetti:2011_chicks_op}

- dolphins (Jaakkola et al 2010)

\item dolphins \citep{jaakkola:2010_what}

- ...

‘The real difficulty is that there is no reward for the great majority of cats in retrieving an unmoving, silent, odor-free, covered-up object from which their attention has been distracted, and hence the cats will not show that they know where it is.’

(Triana & Pasnak 1981, p. 138)