Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Knowledge of Mind

(Premack & Woodruff 1978: 515)

belief

‘Maxi puts his chocolate in the BLUE box and leaves the room to play. While he is away (and cannot see), his mother moves the chocolate from the BLUE box to the GREEN box. Later Maxi returns. He wants his chocolate.’

blue

box

green box

I wonder where Maxi will look for his chocolate

‘Where will Maxi look for his chocolate?’

Wimmer & Perner 1983

Wimmer & Perner 1983

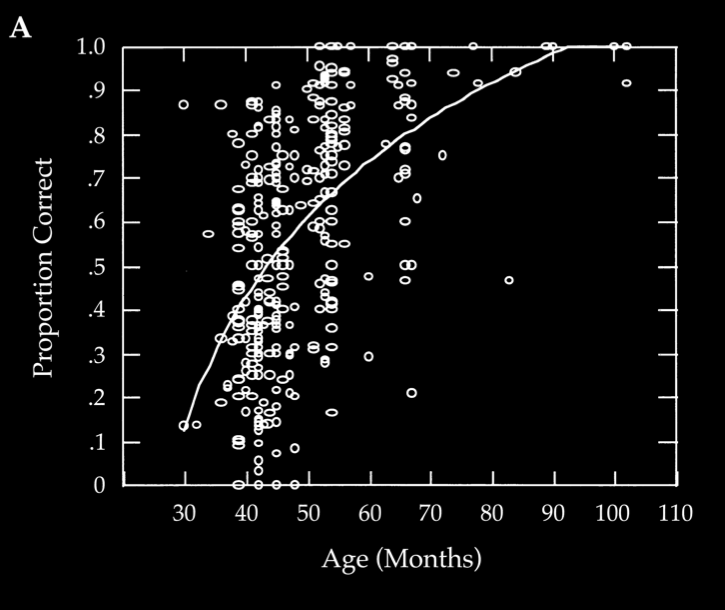

Wellman et al 2001, figure 2A

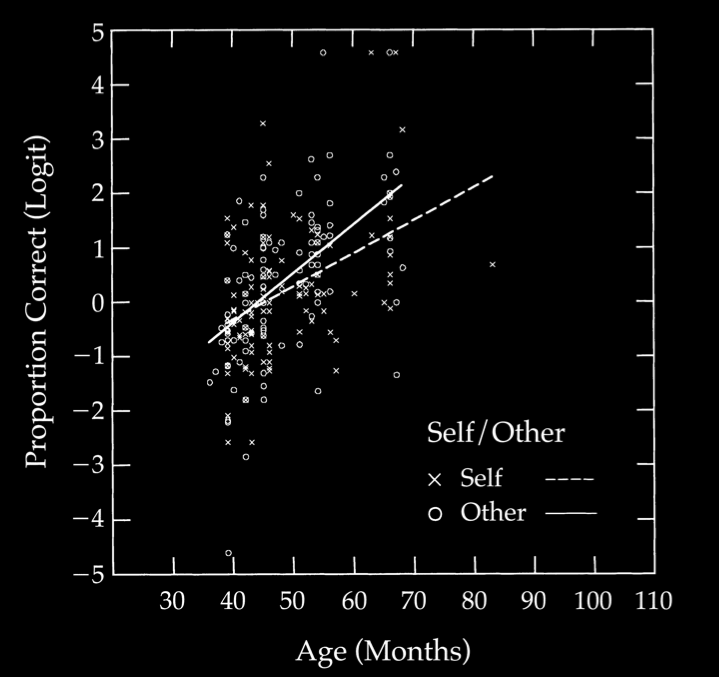

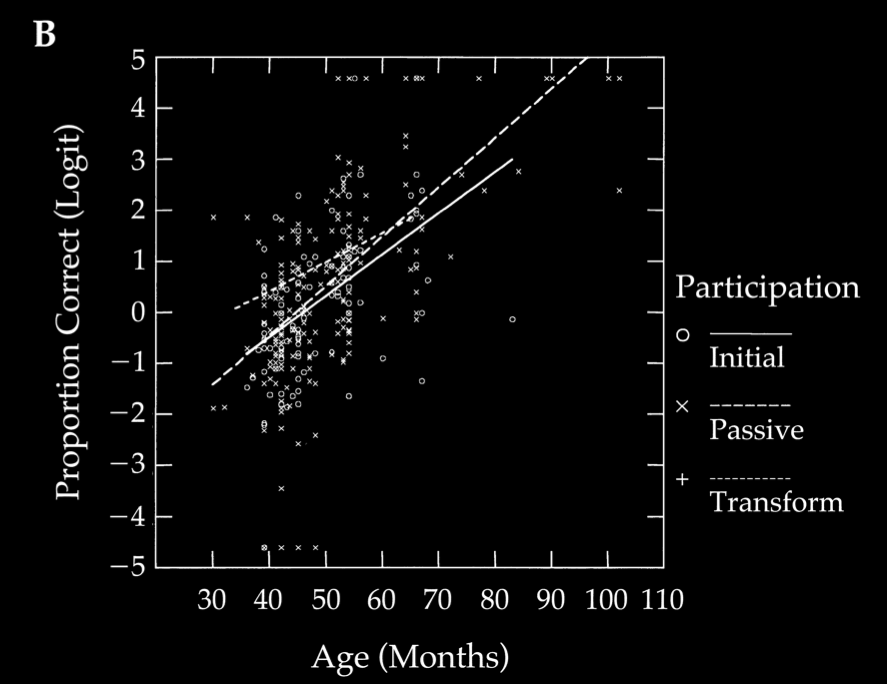

Wellman et al 2001, figure 5

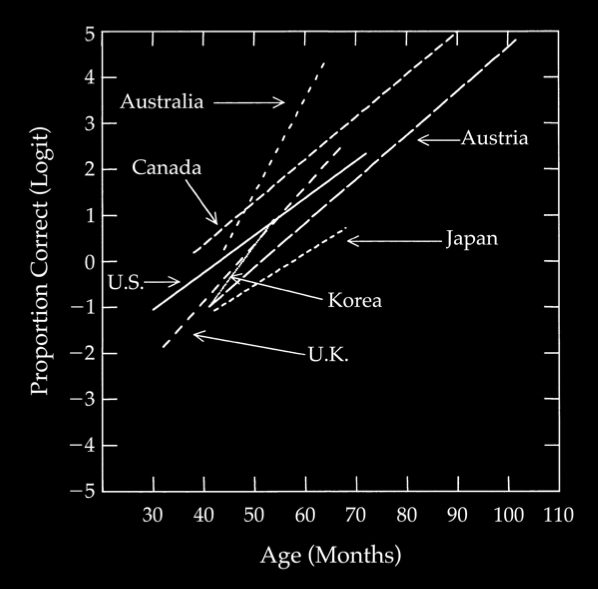

Wellman et al 2001, figure 6

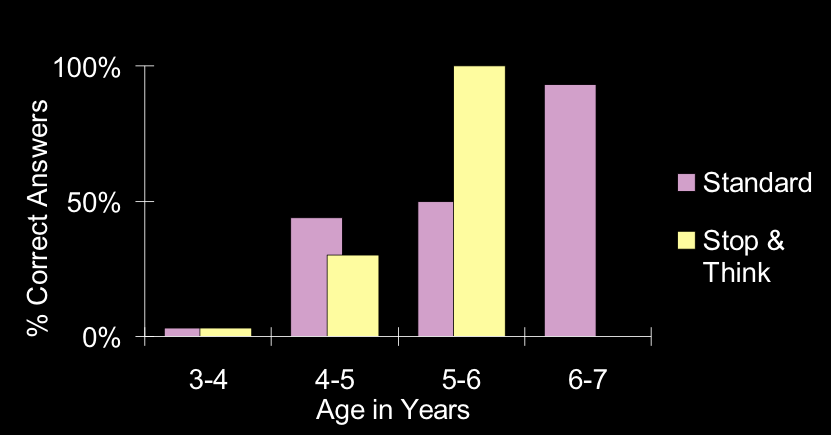

Wellman et al 2001, figure 7

Sellars' Myth of Jones

but ...