Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

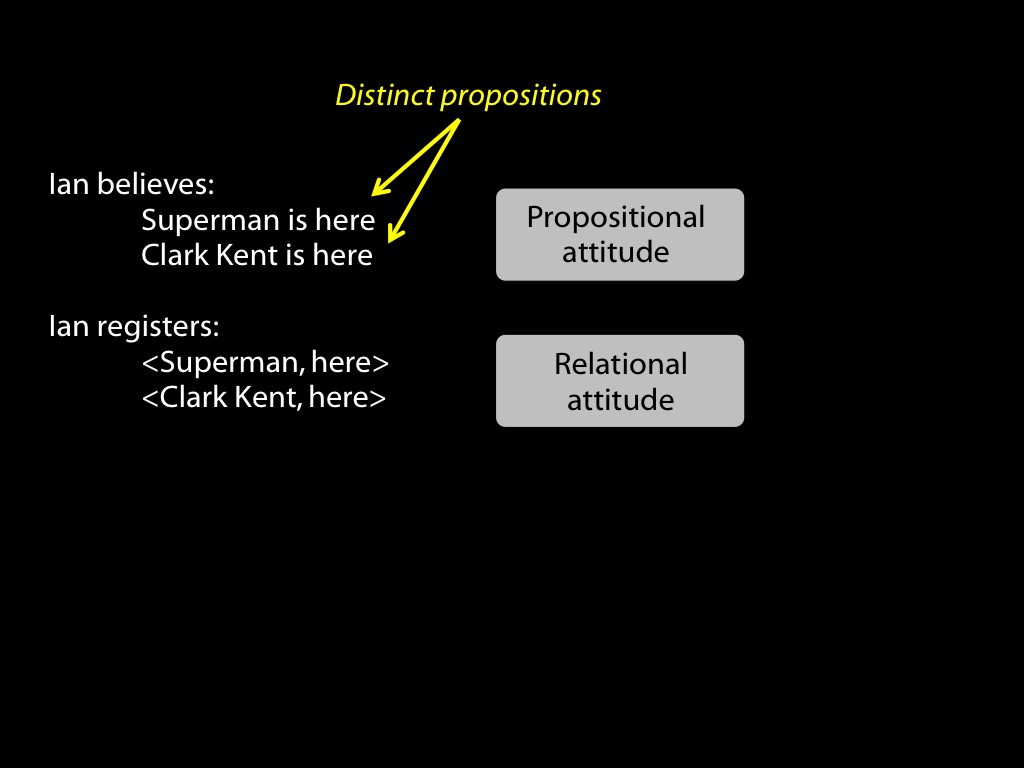

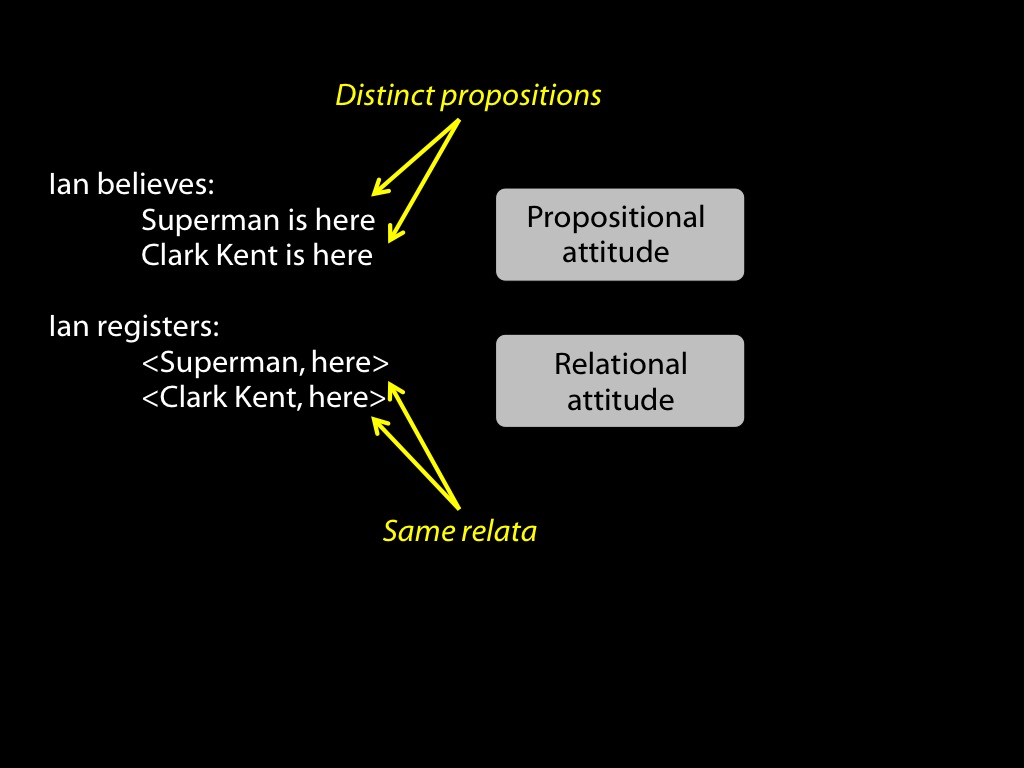

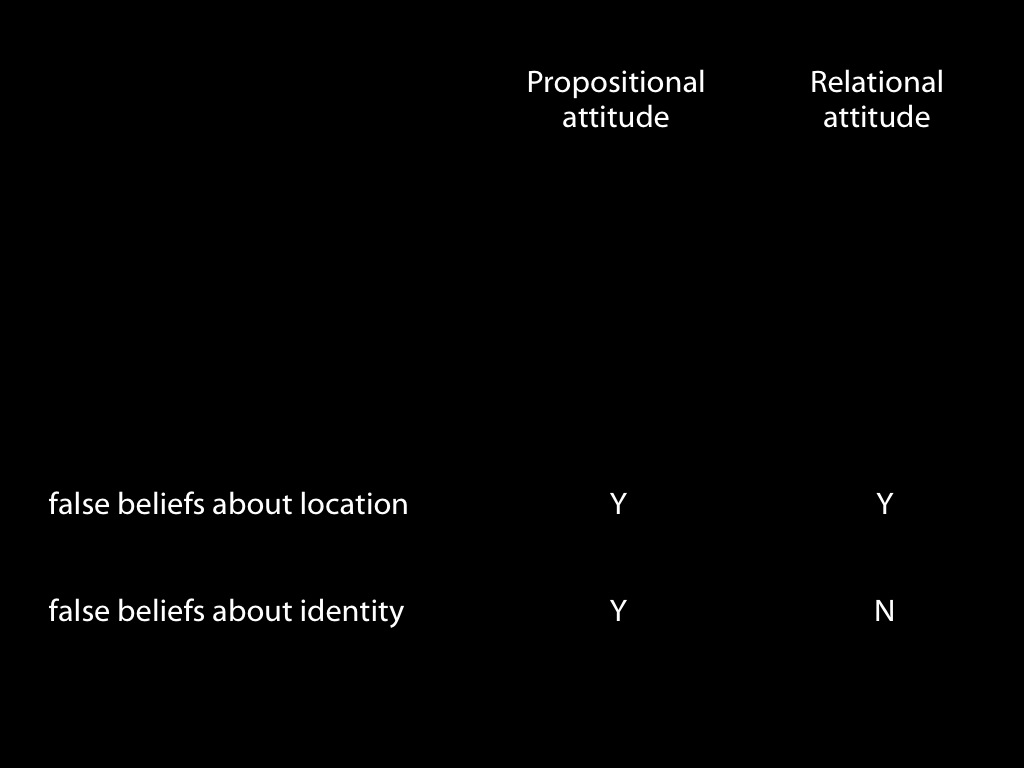

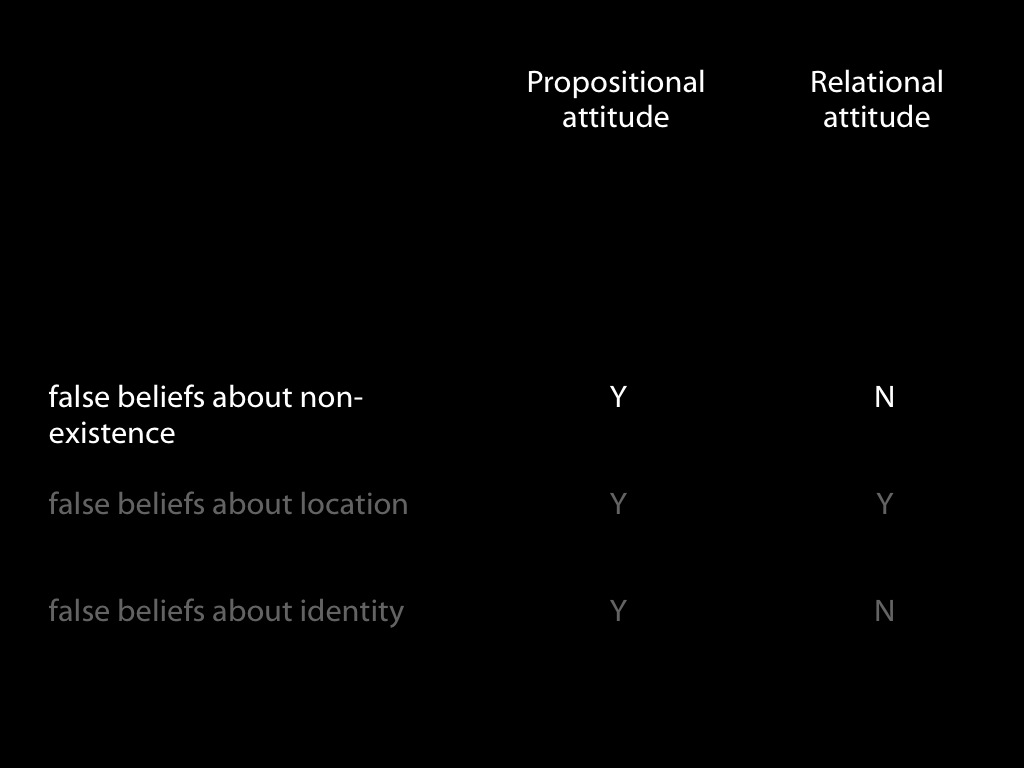

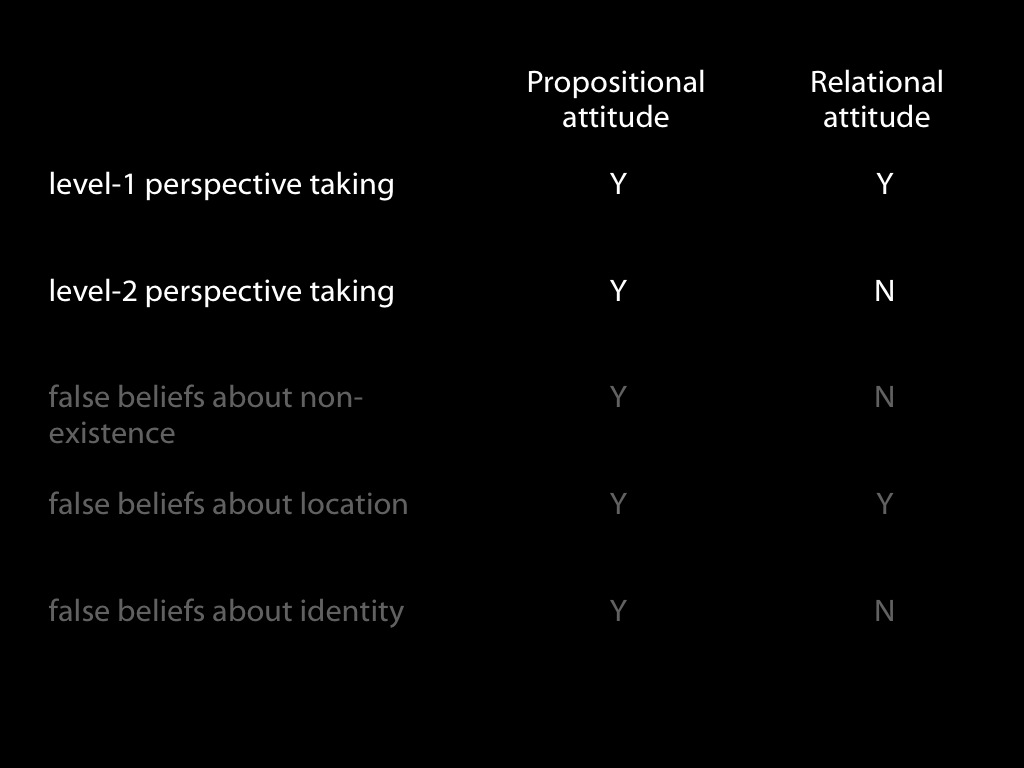

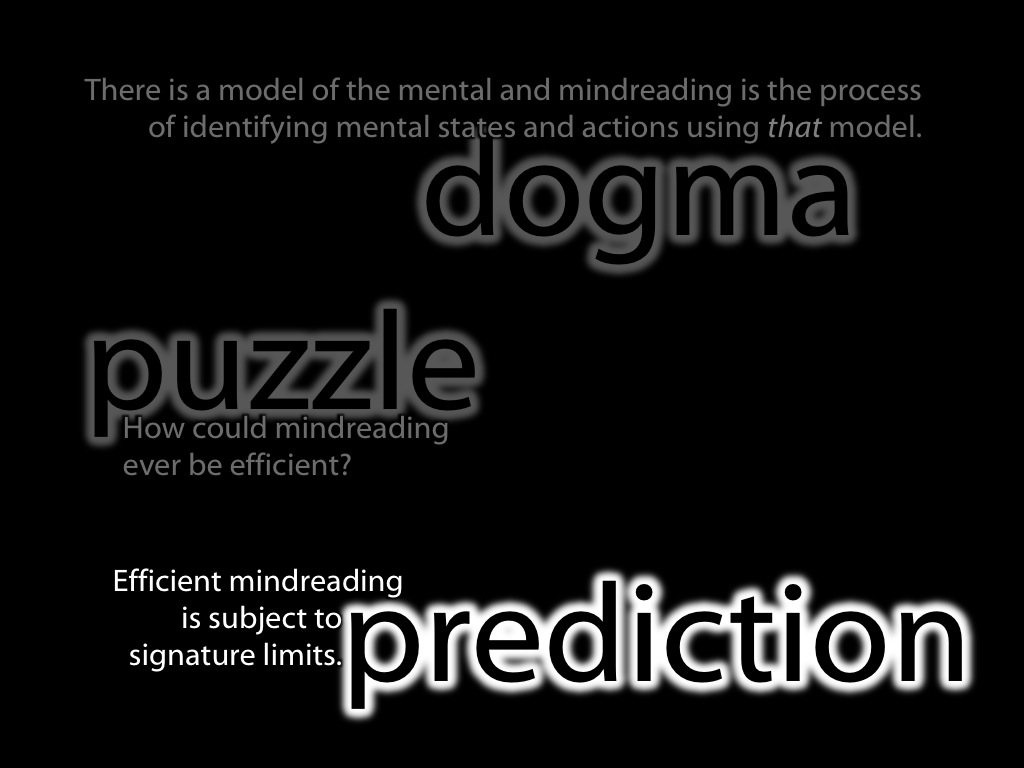

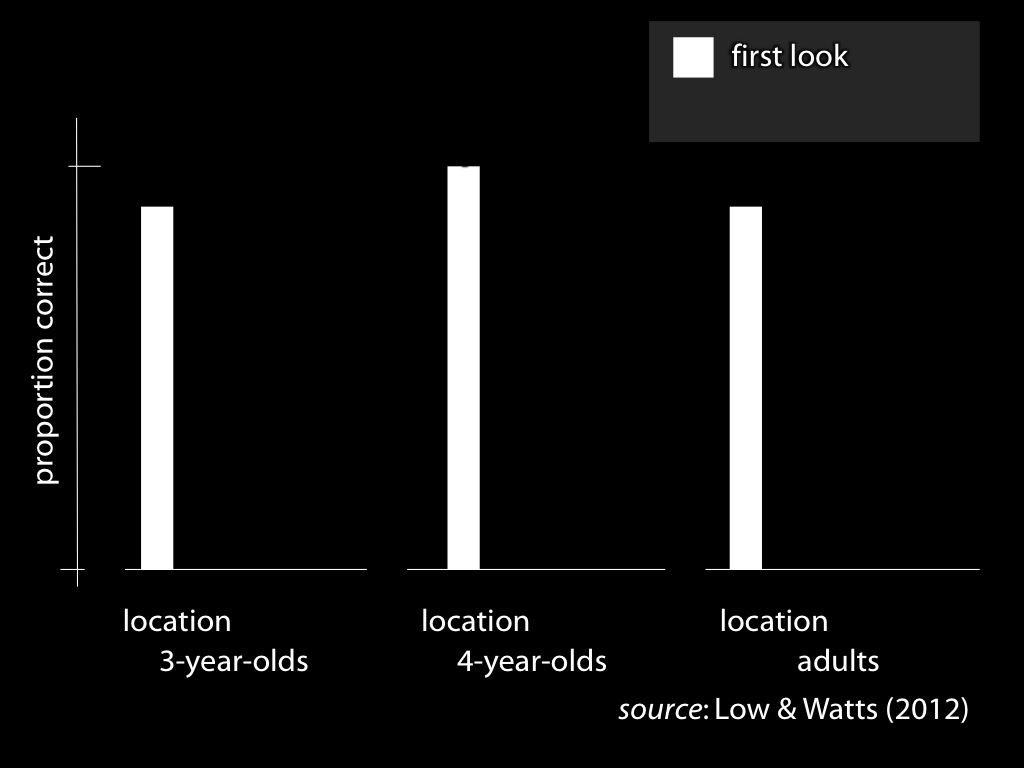

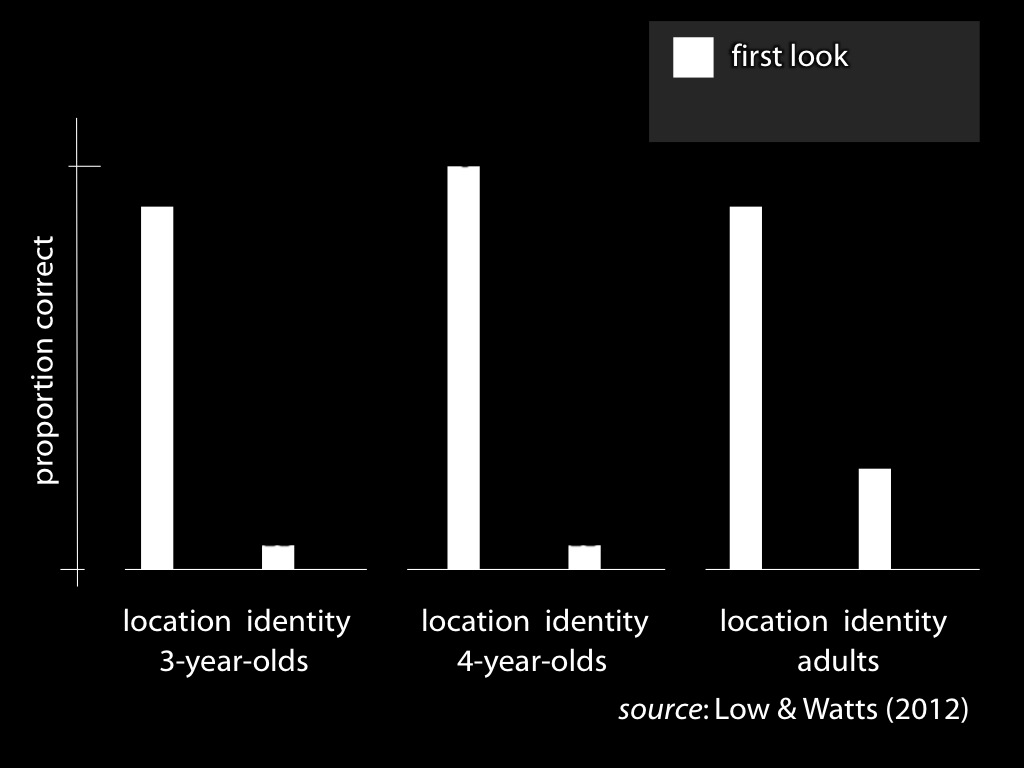

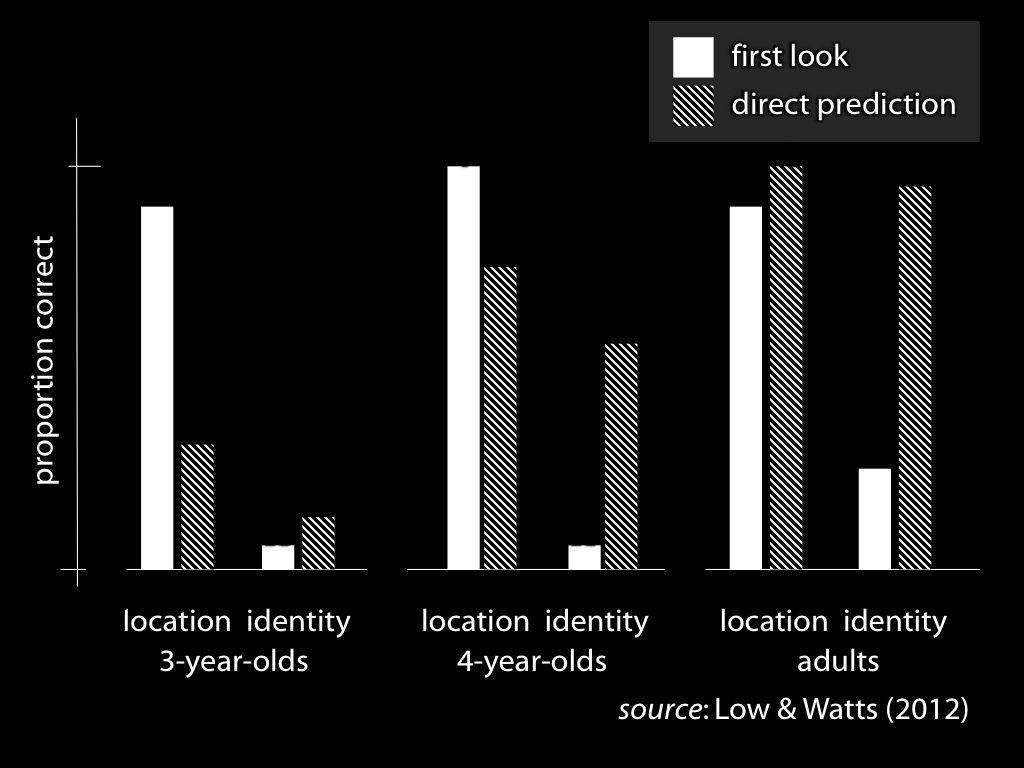

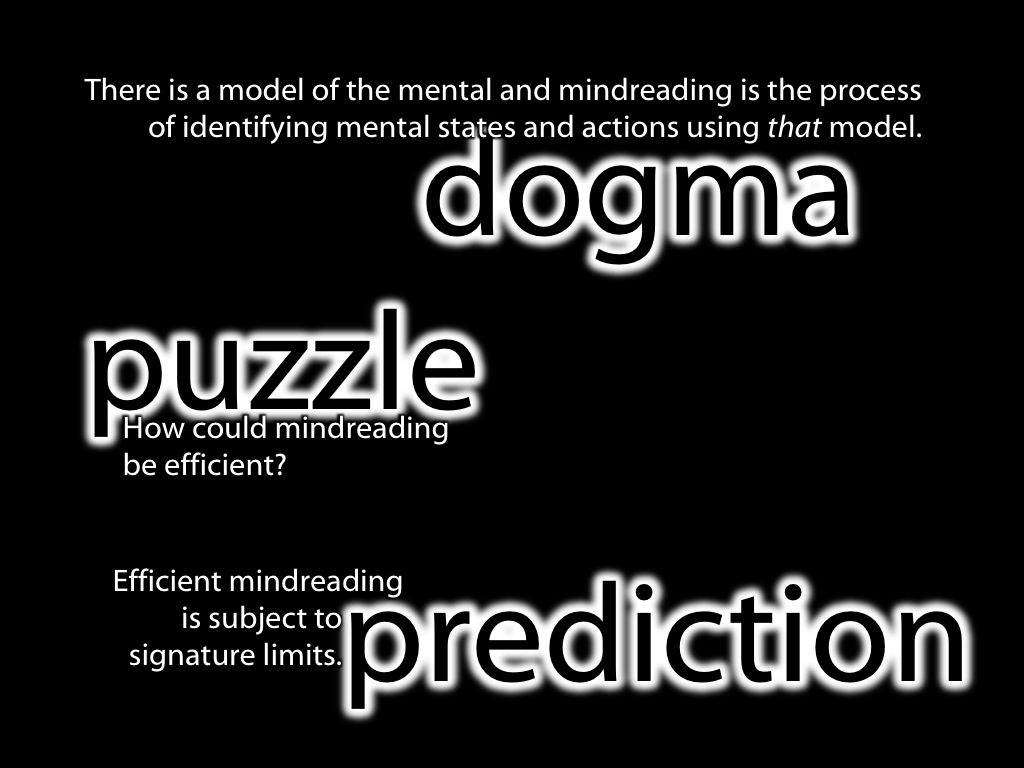

Signature Limits Generate Predictions

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[width=0.25\textwidth]{fig/signature_limits_table.png}

\end{center}

\begin{center}

\includegraphics[width=0.3\textwidth]{fig/low_2012_fig.png}

\end{center}

challenge

Explain the emergence, in evolution or development, of mindreading.

So let me conclude.

The challenge we have been addressing was to understand the emergence of mindreading.

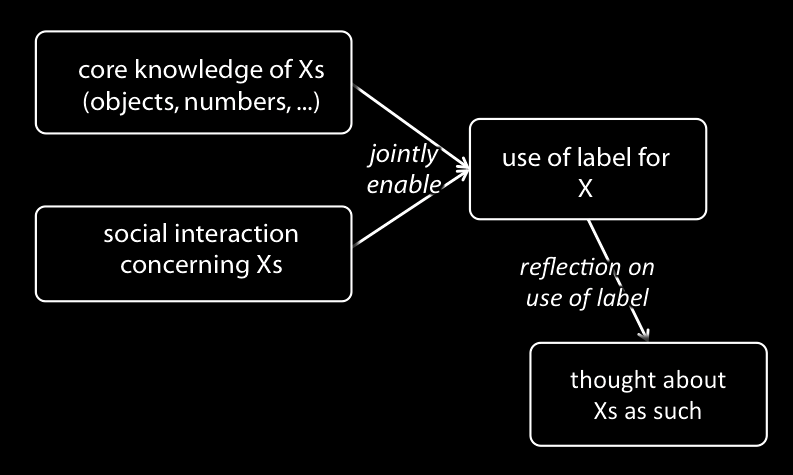

Initially this seemed straightforward: you learn this from social interaction using language as a tool (compare Gopnik's theory theory).

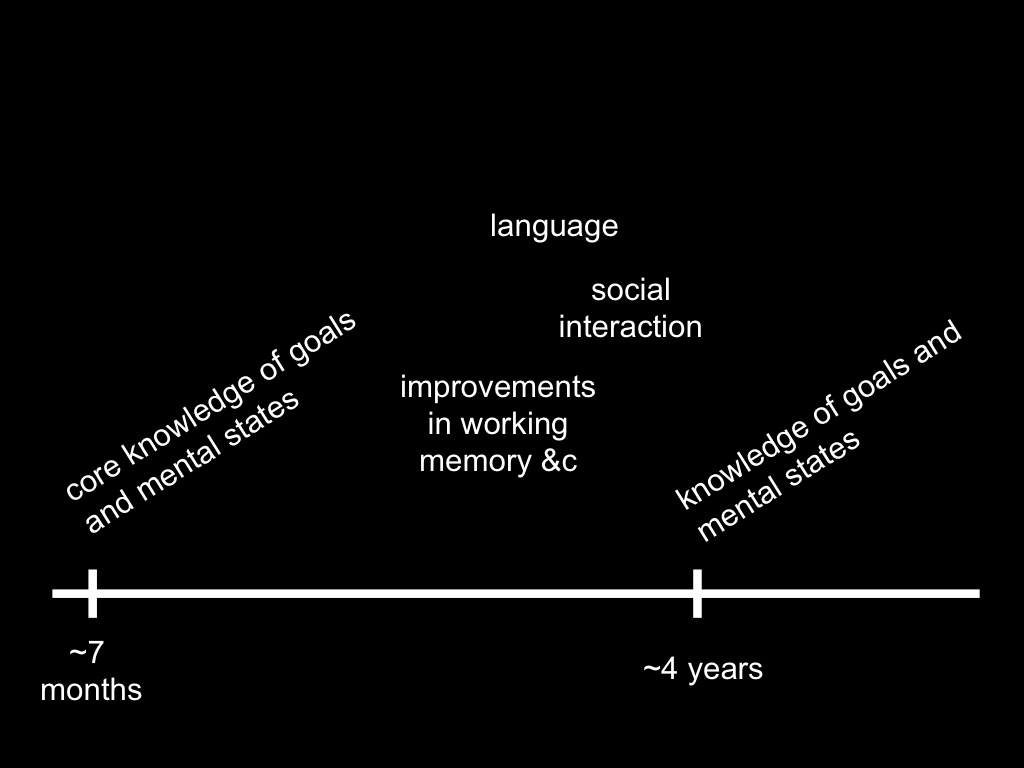

However, the discovery that abilities to track beilefs exist in infants from around 7 months or earlier initially suggested a different picture:

one on which mindreading was likely to involve core knowledge.

But, as always, things are not so straightforward. The evidence is apparently conflicting.

There are actually two conflicts, not one: developmentally (A- & B-tasks) and in adults, automaticity.

The existence of two puzzles gives us confidence that the conflict is not merely a methodological artefact.

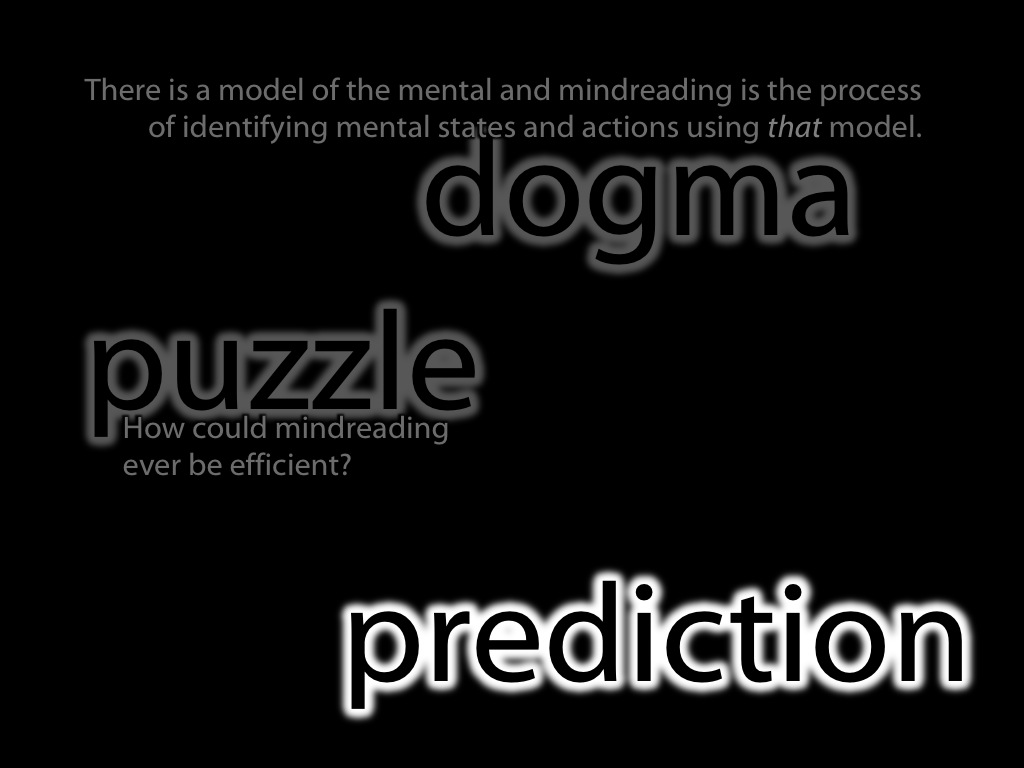

The solution is to recognise that there are modules, but there was an obstacle to the hypothesis that mindreading could be modular (*cognitive efficiency)

In constructing minimal theory of mind we've earned the right to solve them by appeal to modularity. (NB: it's modularity rather than mTm that explains the discrepancy; mTm is important because (i) it explains efficiency; and (ii) it generates predictions via signature limits)

Now the idea that there are both modular and non-modular mindreading enables us to solve the two puzzles (developmentally (A- & B-tasks) and in adults, automaticity.).

However, this resolution of the puzzles doesn't answer our overall challenge about the origins of knowledge of other minds.

In fact it complicates the account of the origins of knowledge of other minds, makes the challenge seem harder rather than easier to meet.

We can't give a theory theory / learning account; and we also can't give a straightforward core knowledge account.

Instead we need something a bit more complex.

I haven't tried to offer an account of what that thing is yet, and that isn't the point of this lecture.

But let me close by describing how I would approach it.

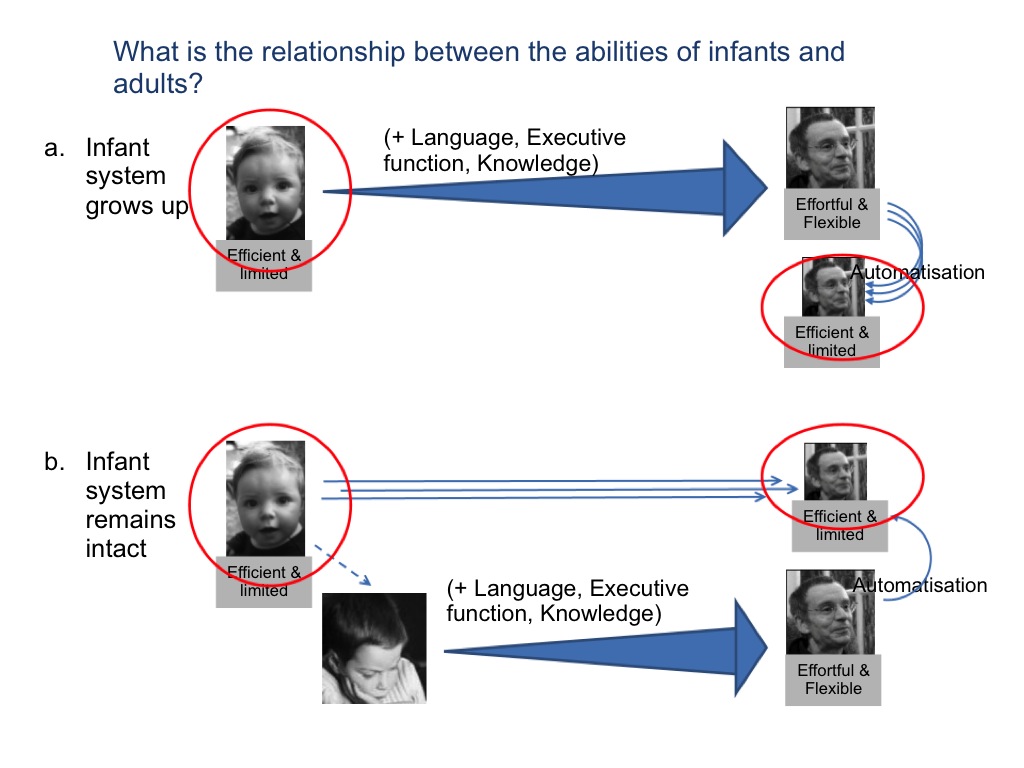

A key issue is the relation between infant and adult competence ...

Infant competence retained in adults (matching signature limits from Low & Watts), as in the cases of colour (and probably physical objects too).

Now if we accept this, it is tempting to conjecture that the later developing mindreading abilities involve a process of rediscovery ...

- theme A: explain the origins of knowledge of others minds : development as rediscovery. There is a modular capacity ( = core knowledge).

But this doesn't lead to adult-like understanding for years, and the acquisition of adult-like understanding hinges on language; may involve completely different model of mental states.

development as rediscovery.

Let me pause to evalaute the picture I offered earlier in the light of what we've learnt so far.

(I hesitate to do this because it shows the picture I offered you isn't very good.)

Take each case in turn.

For colour it works quite well, providing, as I suggested last week, that acquiring words is a creative process of social interaction.

What about physical objects? Here there's no indication that using labels for objects drives a developmental change, and it's hard to see why it would.

(It's more plausible that tool use rather than word use matters; but even this is is hugely speculative.)

So no marks for that case at all.

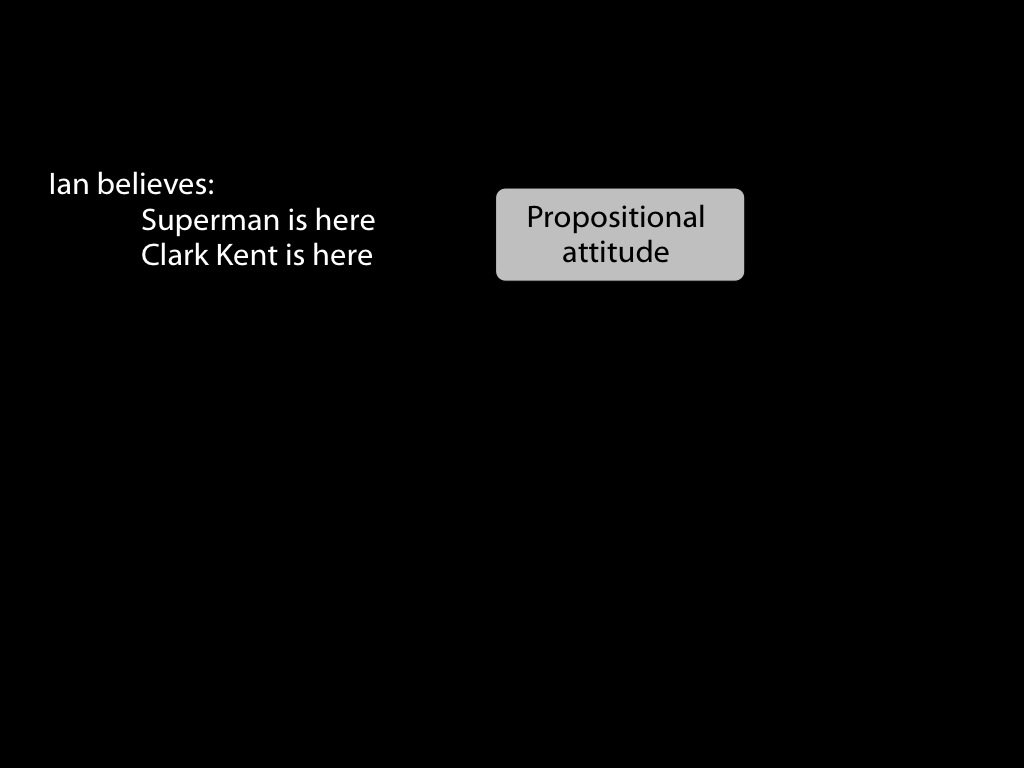

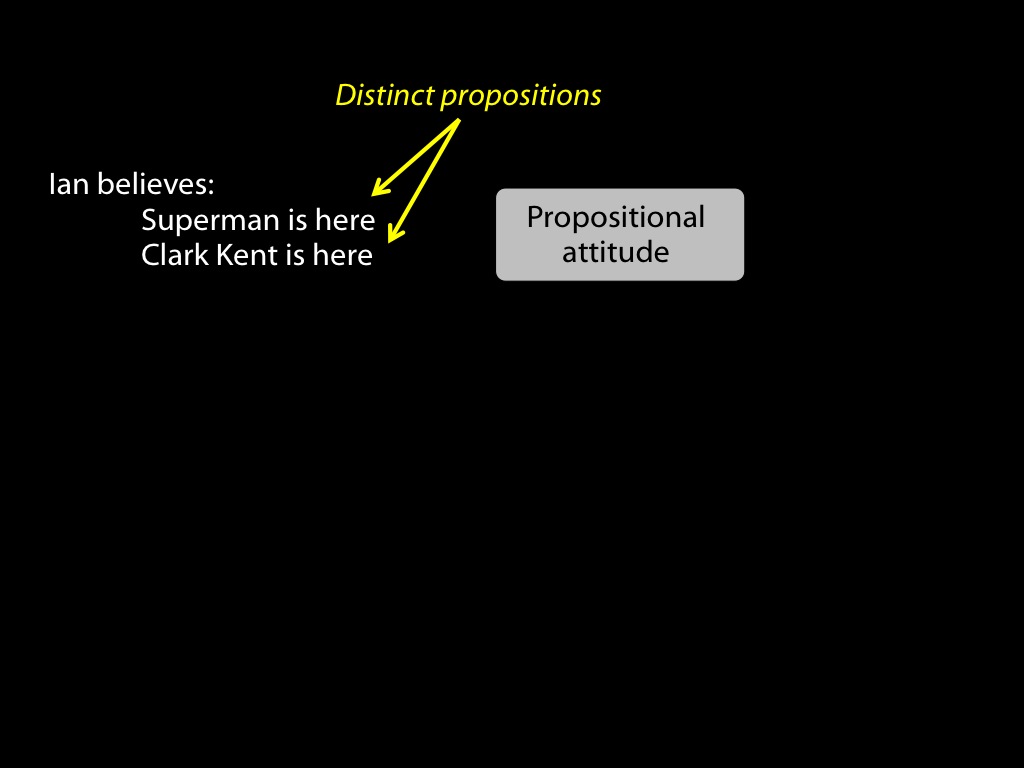

What about minds, and in particular beliefs?

Superficially things look better here. There is both evidence that rich forms of social interaction facilitate development \citep{Hughes:2006fu}

and also evidence that language matters in various ways \citep{Astington2005ot}.

But these probably don't connect in the simple way I envisage.

Social interaction might matter because it provides experiences of perspective differences, or because it motivates children to think about others' minds.

And language might matter because having sentences around enables them to keep track of beliefs, or because using relative clauses might clue them in to a relation between beliefs and what utterances of sentences express.

So here the picture isn't right, but it might not be a million miles off either ...

It's wrong to think that labelling beliefs matters; but it may be that being able to talk about beliefs (implicitly or otherwise) does matter for coming to have knowledge of them.