Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Communication with Words: A Question

Linguistic communication is 'the indispensable instrument of fine-grained interpersonal

understanding' (Davidson 1990: 326).

It enables us to pool knowledge and coordinate our actions.

Possessing language also allows us to share our lives in ways far more intimate than we could

manage without it.

Today's question is,

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

This question is complex because language is complex ...

It is also complex because we're starting at the far end of a chain.

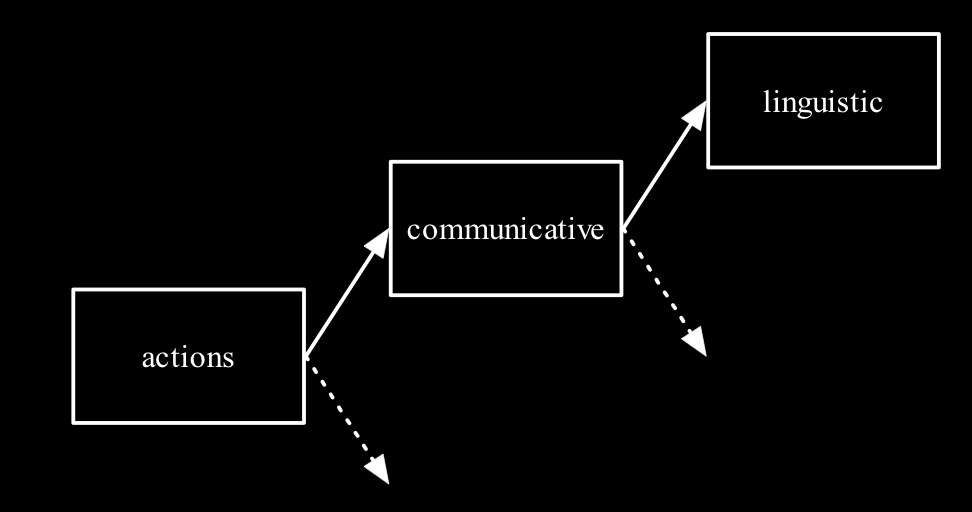

You might think, before we ask about communication with words we should ask about communicative

actions, and before we ask about communicative actions we should ask about actions.

I wondered about aproaching it that way too, starting with action and working up.

But in the end I thought that right now you most of you are probably most interested in language, so most of you would probably find it most interesting to go backwards.

There is reason to doubt that we can seriously discuss the nature of humans' abilities to

communicate at all.

Chomsky holds that ‘the topic of successful communication in the actual world is far too

complex and obscure’ to say anything systematic about (Chomsky 1992: 120). It’s a mistake, he

thinks, to try to understand language by focussing on communication (compare Chomsky 2000: 30).

‘the topic of successful communication in the actual world is far too complex and obscure’

(Chomsky 1992: 120)

I think Chomsky’s challenge is a serious one. We don't need to debate whether Chomsky is right.

We merely need to note that, right now,

not very much is actually known about the nature of communication with words.

So we are asking about the development of abilities to communicate with words,

even though we know much too little even about what it is to communcaite with words.

If we are to make the topic of communiation with words tractabale at all, we must start

by breaking the question down.

To this end we need to ask,

What are the components of an utterance?

The truth is extremely complex.

But we need only a relatively simple picture ...

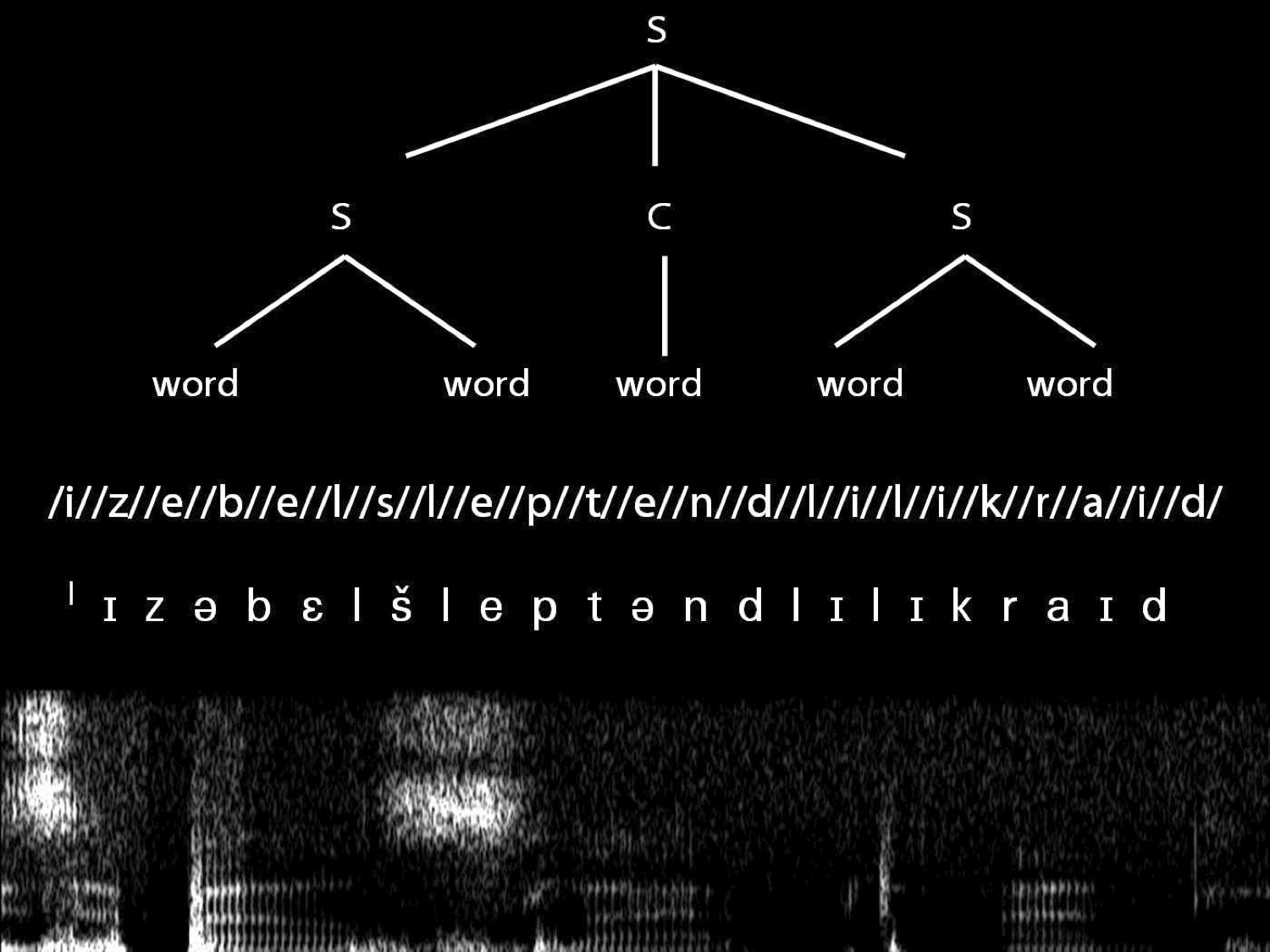

Consider an utterance of sentence like 'Isabel slept and Lily cried'.

What is the structure of this utterance?

First we can break the sentence down into two sentences and a connective.

Then we break these into words.

And the words break down into phonemes.

Which are eventually realised in continous bodily movements and the sounds these produce.

This is a very simplified picture.

But already we can see that comprehending an utterance will involve several steps.

Consider someone experiencing linguistic communication for the first time.

She is experiences continuous bodily movements and their acoustic consequences.

From these she has somehow to extract the phonetic gestures.

And then she has to group the phonetic gestures into words.

And finally she has to work out the syntactic structure of the words.

It turns out that the abilitues to make these different steps involves largely different

mechanisms, and that the steps can be made independently of each other (not that there aren’t

bottom-up and top-down effects, just that these appear to be inessential in some cases).

Our question can be broken down accordingly.

Our question, How do humans first come to communicate with words?

We can break the process of language comprehension into a series of transitions, from bodily

movements and their acoustic effects to phonemes, etc.

And we can think of language production as involving the same transitions, but in reverse.

And then our question can be broken down accordingly.

We don't have to ask how humans come to have abilities to communicate by language all in one go.

Instead we can ask how humans come to be able to identify phonemes in continous bodily movements and their acoustic effects, and how they come to identify words from uninterrupted sequences of phonemes, and so on.

In this way, our question becomes tractable.

So our question,

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

Is much to large a question to consider.

What I am going to--and what many researchers have done--is to focus on 1-word utterances.

This means (a) ignoring syntactic structure; and (b) taking for granted that infants can

identify various utterances of a particular word as actions of a single type.

In effect, then, we are focussing on meaning in its simplest form.

This is not to say that questions about syntax, phoneme recognition and the rest are

unimportant. On the contrary, if I had more time I would devote a lecture to each of these.