Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Core Knowledge

The Beginning of the End

What is core knowledge? What are core systems (≈ modules)?

Why don’t I know the answers?

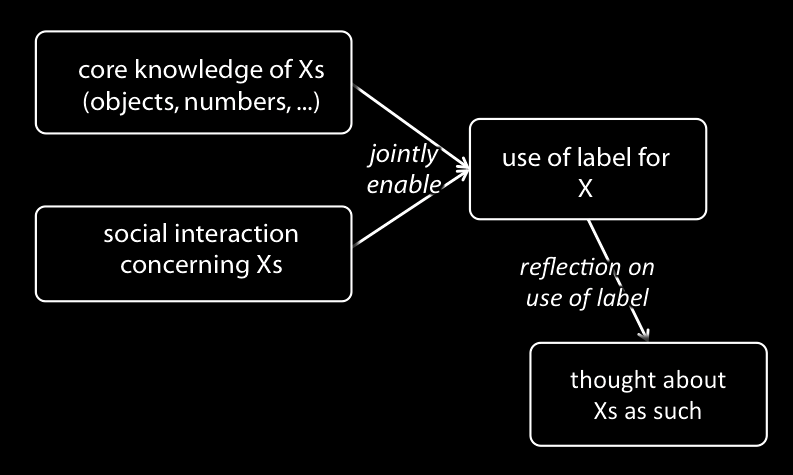

‘We hypothesize that uniquely human cognitive achievements build on systems that humans share with other animals: core systems that evolved before the emergence of our species.

‘The internal functioning of these systems depends on principles and processes that are distinctly non-intuitive.

‘Nevertheless, human intuitions about space, number, morality and other abstract concepts emerge from the use of symbols, especially language, to combine productively the representations that core systems deliver’

Spelke and Lee 2012, pp. 2784-5

‘All understanding of the speech of another involves radical interpretation’

Davidson 1973, p. 125

But what is core knowledge?

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 517)

‘core systems are

- largely innate,

- encapsulated, and

- unchanging,

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

core system vs module

‘core systems are

- largely innate,

- encapsulated, and

- unchanging,

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

Modules are ‘the psychological systems whose operations present the world to thought’; they ‘constitute a natural kind’; and there is ‘a cluster of properties that they have in common’

- innateness

- information encapsulation

- domain specificity

- limited accessibility

- ...

Why do we need a notion like core knowledge?

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

| syntax | [to follow] | [to follow] |

| number | [to follow] | [to follow] |

If this is what core knowledge is for, what features must core knowledge have?

limited accessibility to knowledge

maximum grip aperture

(source: Jeannerod 2009, figure 10.1)

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

| syntax | [to follow] | [to follow] |

| number | [to follow] | [to follow] |

next: syntax