Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

A Puzzle about Pointing

a puzzle about pointing

Contrast apes with humans ...

‘there is not a single reliable observation, by any scientist anywhere, of one ape pointing for another’.

Tomasello 2006, p. 507

footnote: ‘There is actually one reported incident of a bonobo pointing for conspecifics in the wild (Veà and Sabater-Pi 1998)’

Tomasello 2006, footnote 1

‘no apes point declaratively ever.’

Tomasello 2006, p. 510

Why don’t apes point? (Tomasello’s question)

motor issues?

But they do gesture

understanding action?

But they are sensitive to facts about

the goals of others' actions.

A clue: apes don't comprehend declarative pointing ...

Hare & Tomasello 2004

‘to understand pointing, the subject needs to understand more than the individual goal-directed behaviour. She needs to understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located; that the other tries to inform her about something that is relevant for her’

Moll & Tomasello 2007

Why don’t apes point comprehend pointing gestures?

Informative pointing

To comprehend:

- know that this person is pointing to location L;

- know that by so pointing she is attempting to communicate; and

- know that what she is attempting to communicate is that object X it at L.

To produce:

- know how to point to location L;

- know that by pointing to location L you can communicate with this audience;

- know that what you can communicate is that object X is at L.

Why don’t 3-month-olds point?

Why don’t apes point?

(And why don’t they understand declarative pointing?)

Because they fail to ‘understand that by pointing towards a location, the other attempts to communicate to her where a desired object is located’ (Moll & Tomasello 2007)

But

- What is it to understand this?

- Do 12-month-old humans understand it?

appendix

pointing: referent and context

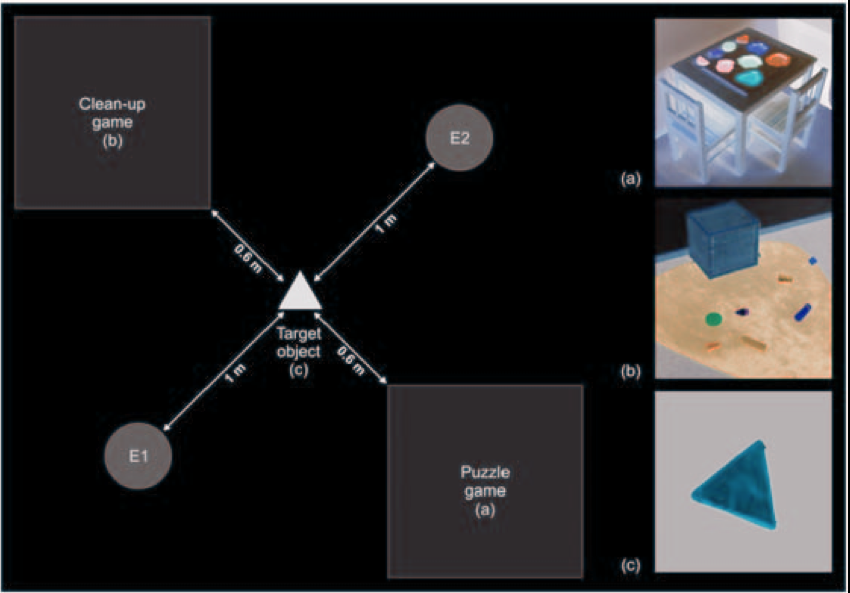

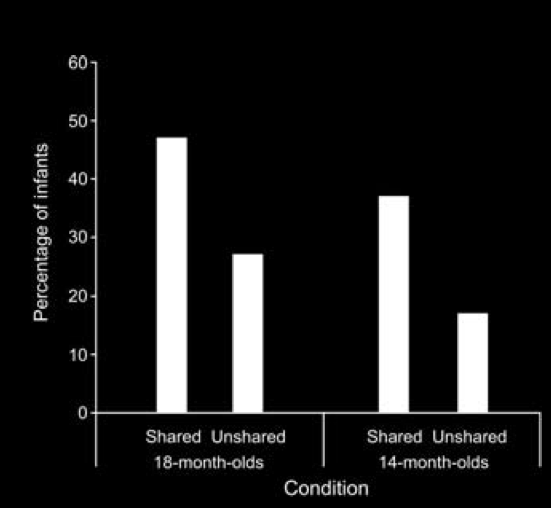

Liebal et al 2009, figure 1

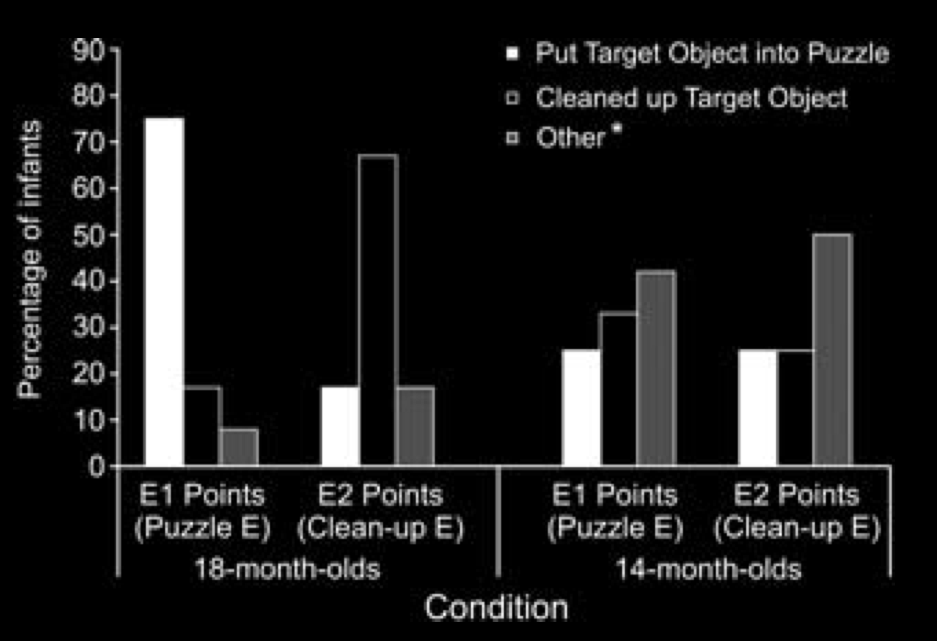

Liebal et al 2009, figure 2

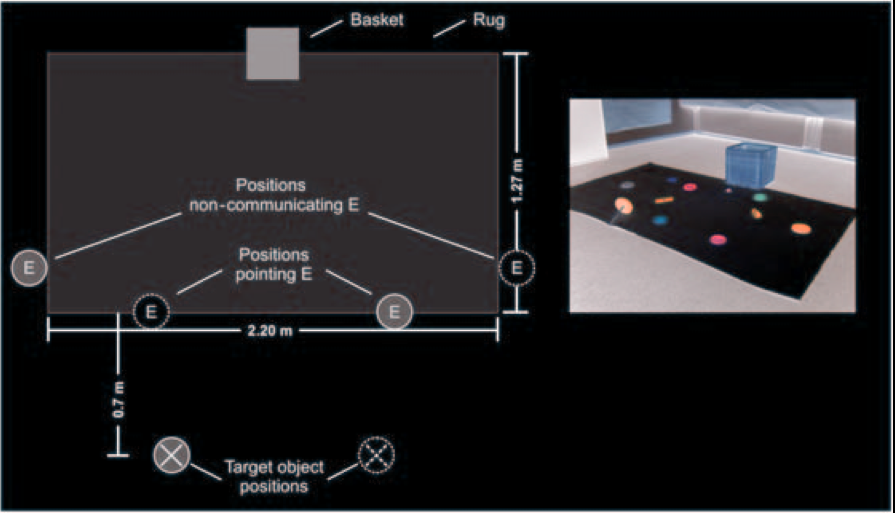

Liebal et al 2009, figure 3

Liebal et al 2009, figure 4