Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

What is a communicative action?

What is a communicative action?

Informative pointing

To comprehend:

- know that this person is pointing to location L;

- know that by so pointing she is attempting to communicate; and

- know that what she is attempting to communicate is that object X it at L.

To produce:

- know how to point to location L;

- know that by pointing to location L you can communicate with this audience;

- know that what you can communicate is that object X is at L.

What is a communicative action?

- Ayesha hits Ben intending to bruise him.

- Ayesha fakes a yawn intending to cause Ben to yawn.

- Ayesha lays a trail of false footprints intended to deceive Ben.

- Ayesha waves at Ben with the intention that he will recognise that she intends him to come over.

Goal: get Ben to come over

Means: get Ben to recognise that I intend to get Ben to come over

Intention: to get Ben to come over by means of getting Ben to recognise that I intend to get Ben to come over.

First approximation: To communicate is to provide someone with evidence of an intention with the further intention of thereby fulfilling that intention.

(compare Grice 1989: chapter 14)

The confederate means something in pointing at the left box if she intends:

- \item that you open the left box;

- \item that you recognize that she intends (1), that you open the left box; and

- \item that your recognition that she intends (1) will be among your reasons for opening the left box.

(Compare Grice 1967 p. 151; Neale 1992 p. 544)

?

Pointing (and non-linguistic communication) involves intentions about recognizing intentions

?

Pointing (and non-linguistic communication) involves intentions about recognizing intentions

shared intentionality

‘infant pointing is best understood---on many levels and in many ways---as depending on uniquely human skills and motivations for cooperation and shared intentionality, which enable such things as joint intentions and joint attention in truly collaborative interactions with others (Bratman, 1992; Searle, 1995).’

Tomasello et al (2007, p. 706)

Theory of communicative action (Tomasello et al?):

- Producing and understanding declarative pointing gestures constitutively involves embodying (?) shared intentionality.

- Embodying shared intentionality involves having knowledge about knowledge of your intentions about my intentions.

Claims about development:

- 11- or 12-month-old infants produce and understand declarative pointing gestures.

- Abilities to communicate play a role in explaning the emergence of knowledge of minds (among other things).

(Also, α rules out a conjecture about minimal theory of mind.)

?

Pointing (and non-linguistic communication) involves intentions about recognizing intentions

first alternative

Convention

‘No speaker needs to form any express intention … in order to mean by a word what it means in the language’

Dummett 1986, 473

‘Interpreting speech does not require making any inferences or having any beliefs about words, let alone about speaker intentions’

Millikan 1984, p. 62

second alternative

‘meaning of whatever sort ultimately rests on intention’

Davidson 1992, p. 298

- ulterior intentions

- semantic intentions

‘The intention to be taken to mean what one wants to be taken to mean is, it seems to me, so clearly the only aim that is common to all verbal behaviour that it is hard for me to see how anyone can deny it.’

Davidson 1994, p. 11

Grice

Goal: get Ben to come over

Means: get Ben to recognise that I intend to get Ben to come over

Intention: to get Ben to come over by means of getting Ben to recognise that I intend to get Ben to come over.

Davidson

Goal: get Ben to come over

Semantic Intention: that Ben take this wave to mean that he should come over.

Ulterior intention: that Ben come over.

Grice

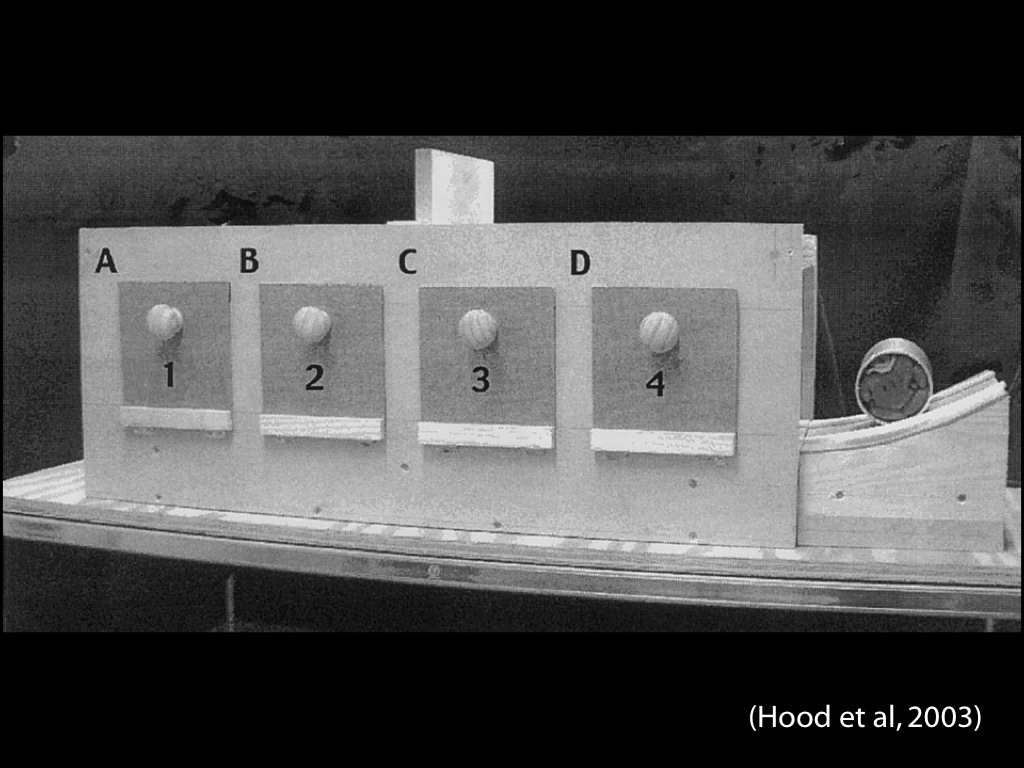

Goal: get Ayesha to select the left container

Means: get Ayesha to recognise that I intend Ayesha to select the left container

Intention: to get Ayesha to selet the left container by means of getting Ayesha to recognisethat I am pointing to the left container with the intention that she select the left container.

Davidson

Goal: get Ayesha to select the left container

Semantic Intention: that Ayesha take this pointing gesture to refer to the left container

Ulterior Intention: that Ayesha select the left container

?

intention to refer

Conclusion for What is a communicative action?

Should we accept that pointing (and linguistic communication) involves intentions about intentions?

- If Grice (and Tomasello et al) are right about communication, then infant pointing involves sophisticated insights into others’ minds.

- But there are alternatives to the Gricean story.

- If Davidson’s* alternative is right, communication requires understanding intentions about meaning or reference but not necessarily sophisticated insights into others’ minds.

Conclusion for Pointing

- 11- and 12-month-old infants can point to (i) request, (ii) inform and (iii) initiate joint engagement.

- ... and they can understand these kinds of pointing gesture.

- Understanding pointing requires more than associating gestures with their referents and understanding goal-directed action (see: why don’t apes & 6-month-olds point)

- But what more is required?

Is it shared intentionality?

And what is that anyway? Is that something inspired by, and adapted from, Grice?