Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Action: The Basics

When do human infants first track goal-directed actions

rather than mere movements only?

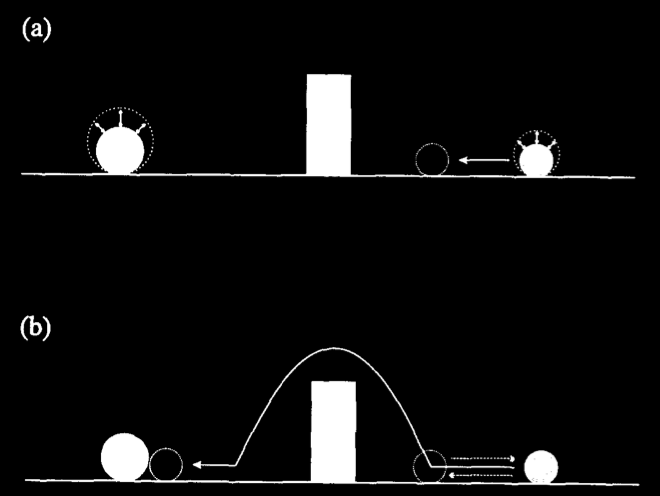

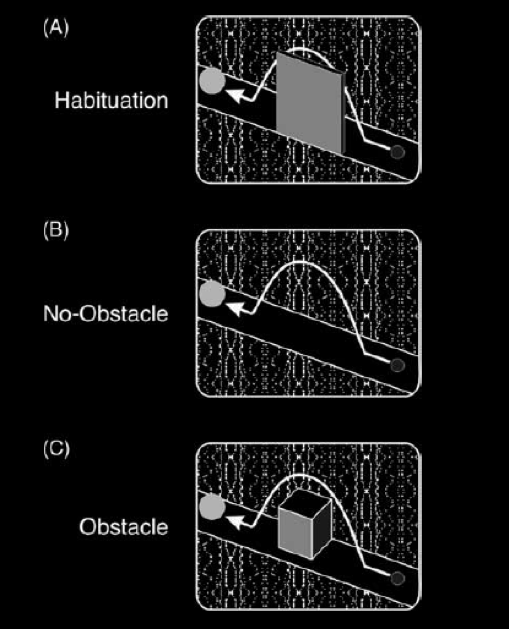

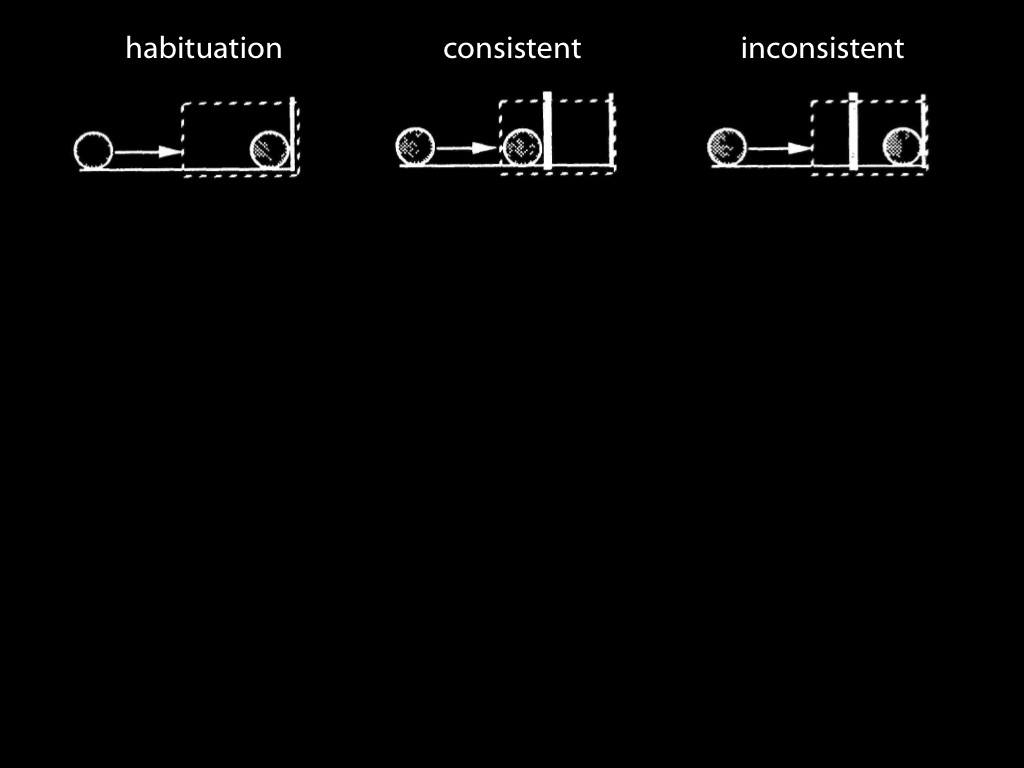

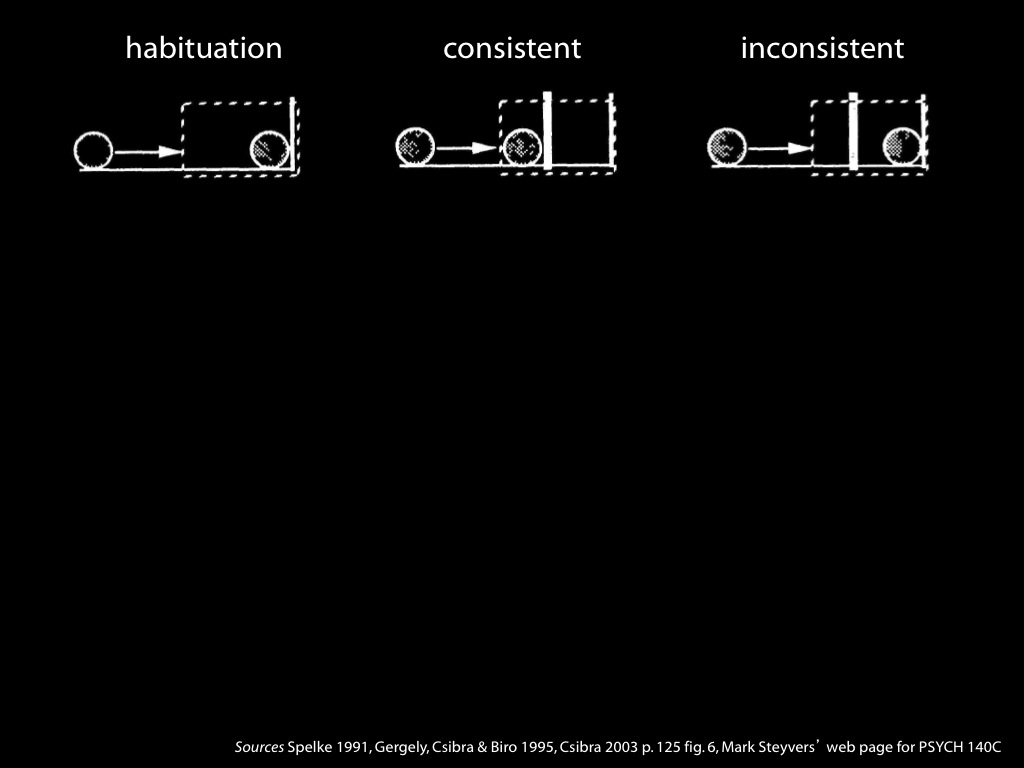

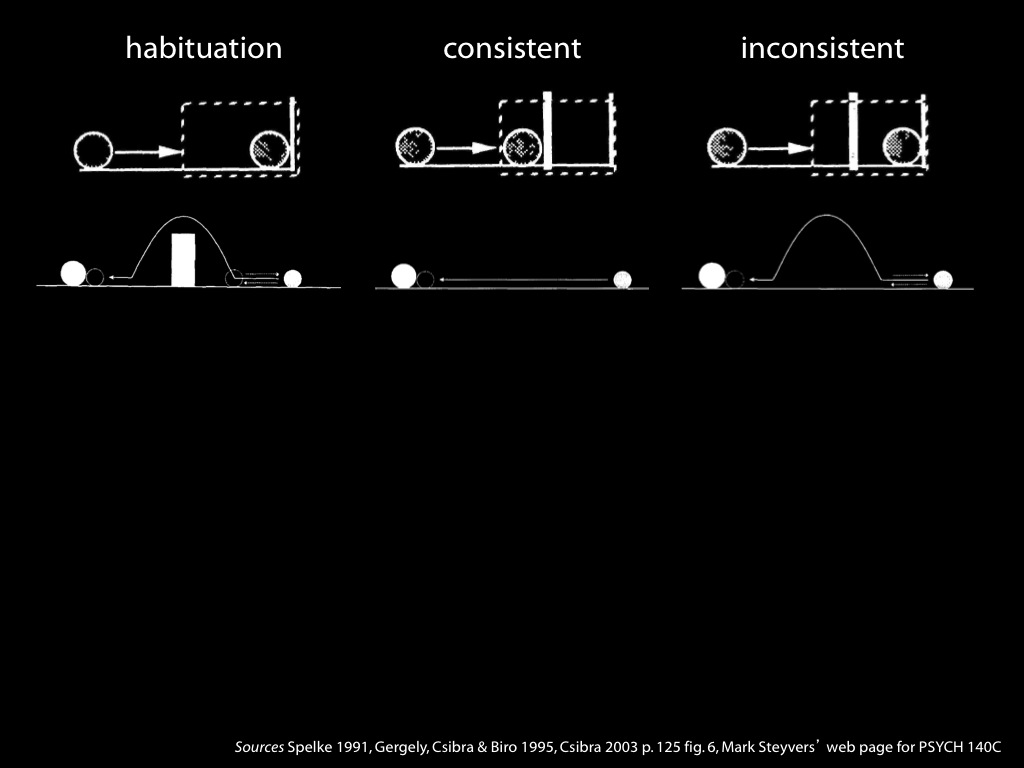

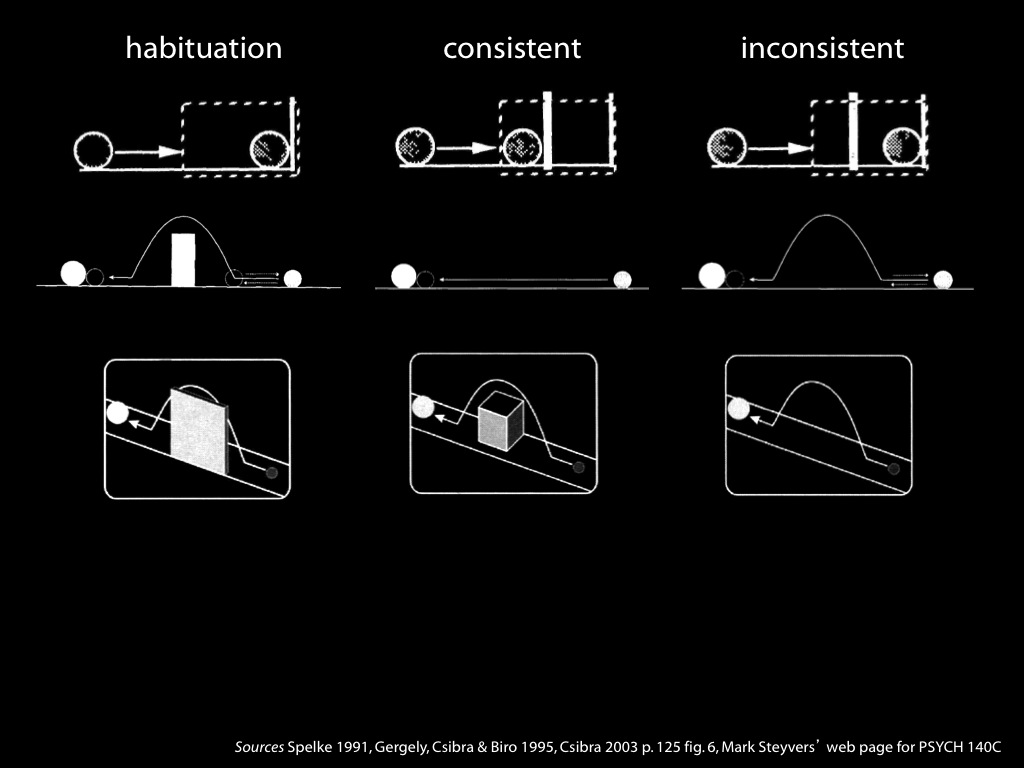

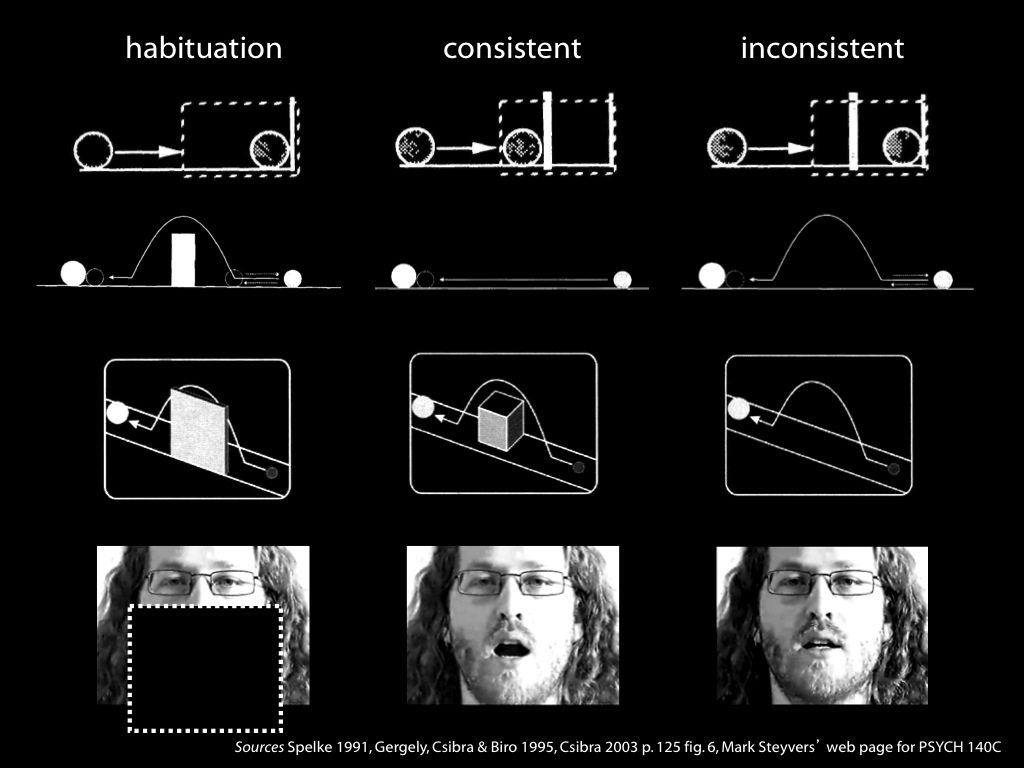

Gergely et al 1995, figure 1

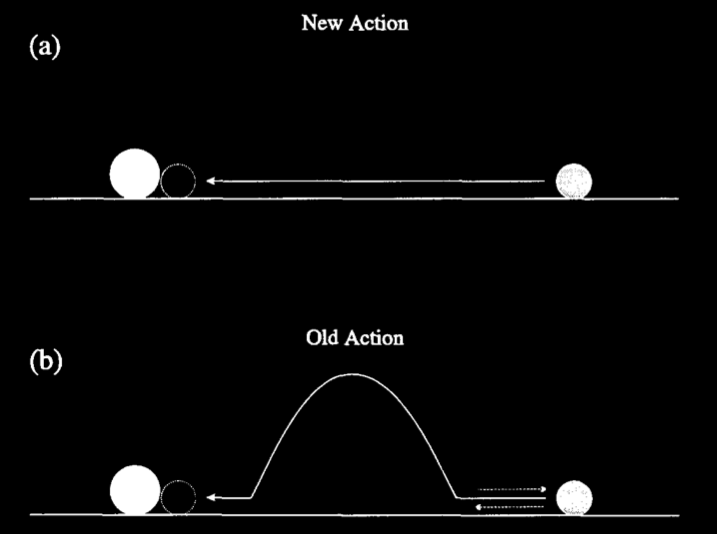

Gergely et al 1995, figure 3

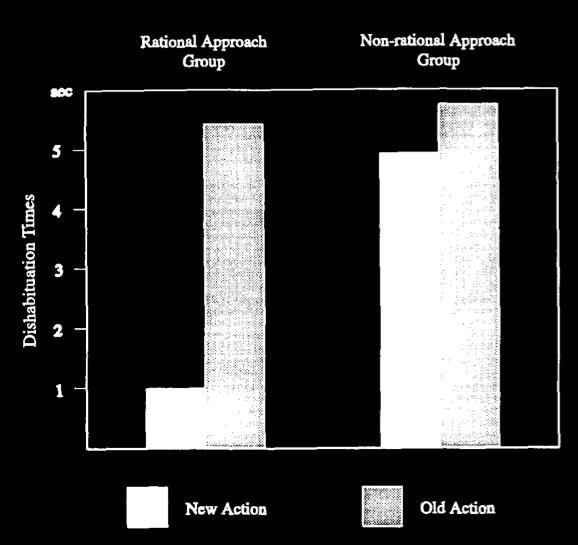

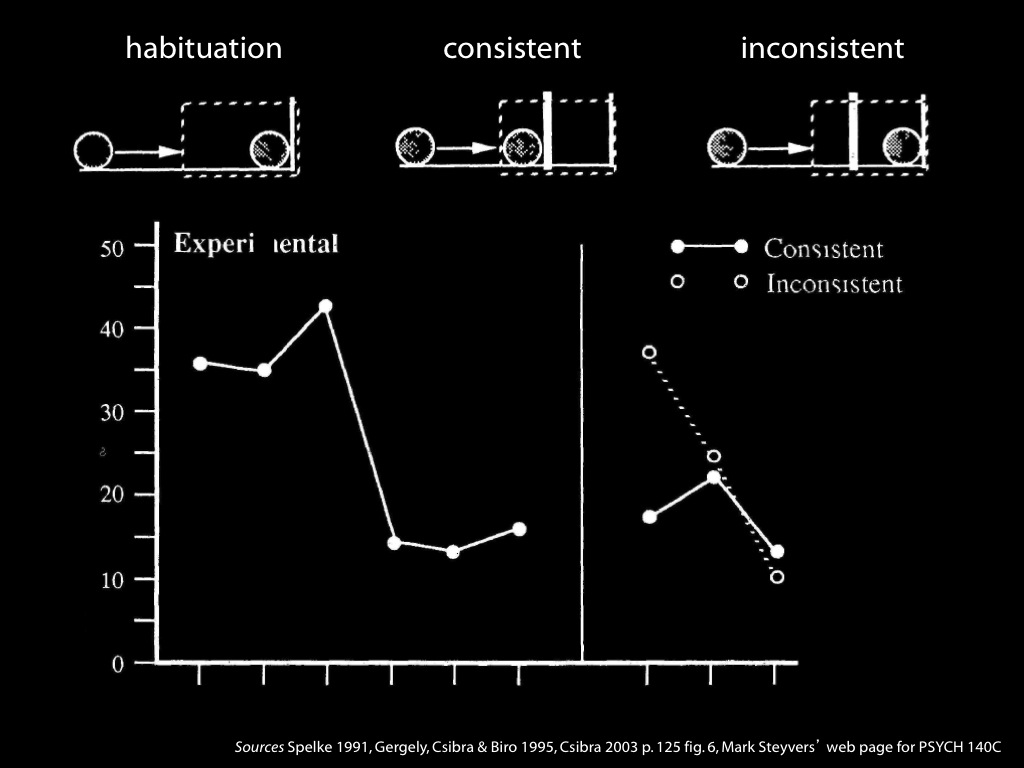

Gergely et al 1995, figure 5

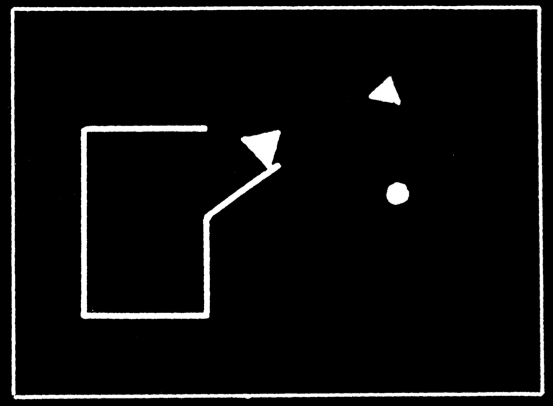

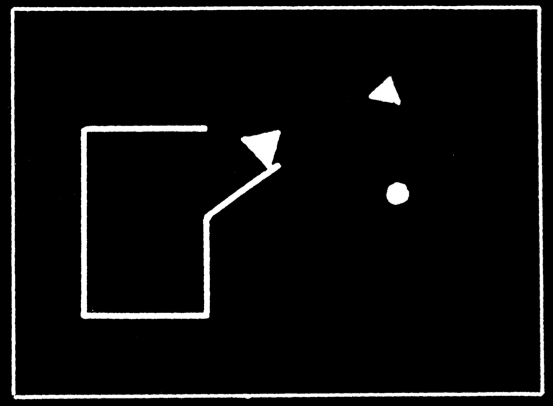

Heider and Simmel, figure 1

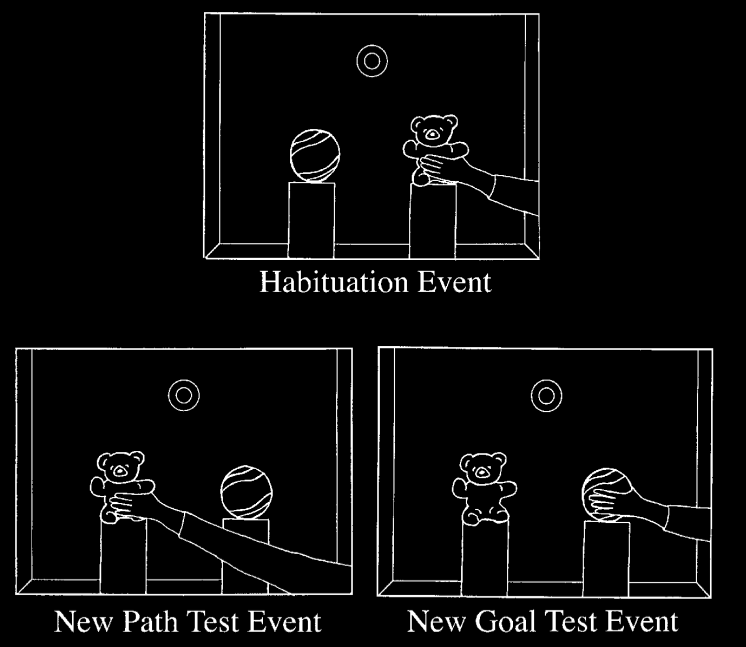

Woodward et al 2001, figure 1

Csibra et al 2003, figure 6

human adults

Heider and Simmel, figure 1

automatic? perceptual?

‘just as the visual system works to recover the physical structure of the world by inferring properties such as 3-D shape, so too does it work to recover the causal and social structure of the world by inferring properties such as causality’

Scholl & Tremoulet 2000, p. 299

evidence?

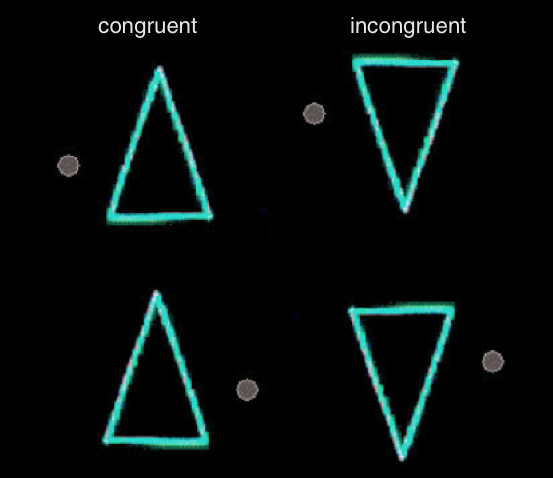

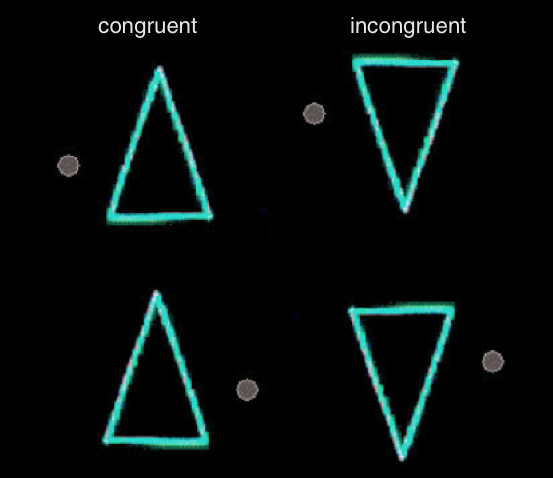

Zwickel et al 2011, figure 1

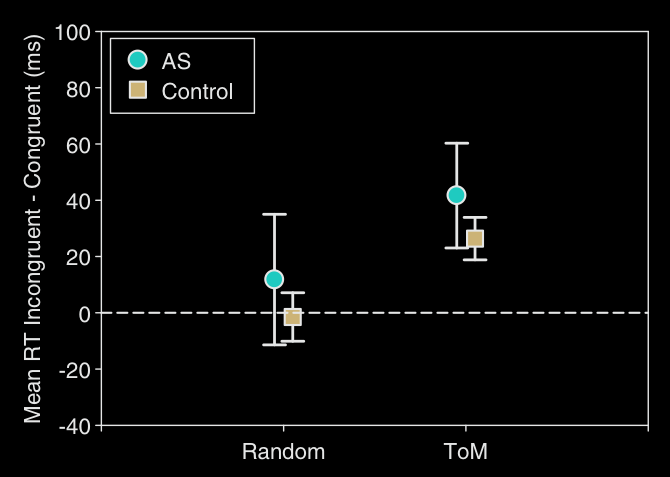

Zwickel et al 2011, figure 2

Zwickel et al 2011, figure 1

altercentric interference

nonhuman primates

So far ...

- Infants track the goals to which actions are directed from around three months of age.

- Adults’ abilities to track goal-directed action may resemble their abilities to track causal interactions in being (i) automatic and perhaps even (ii) perceptual.

core knowledge of

- (colour)

- physical objects

- mental states

- (syntax)

- action

- number