Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Does Infants’ Model of Action Involve Intentions?

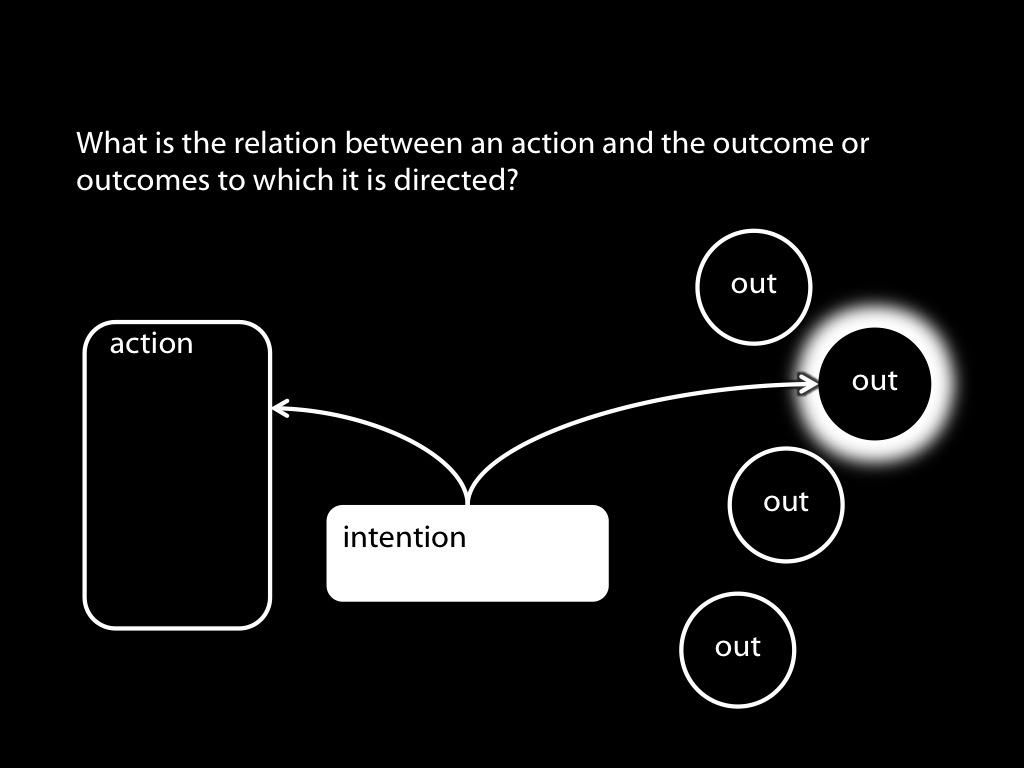

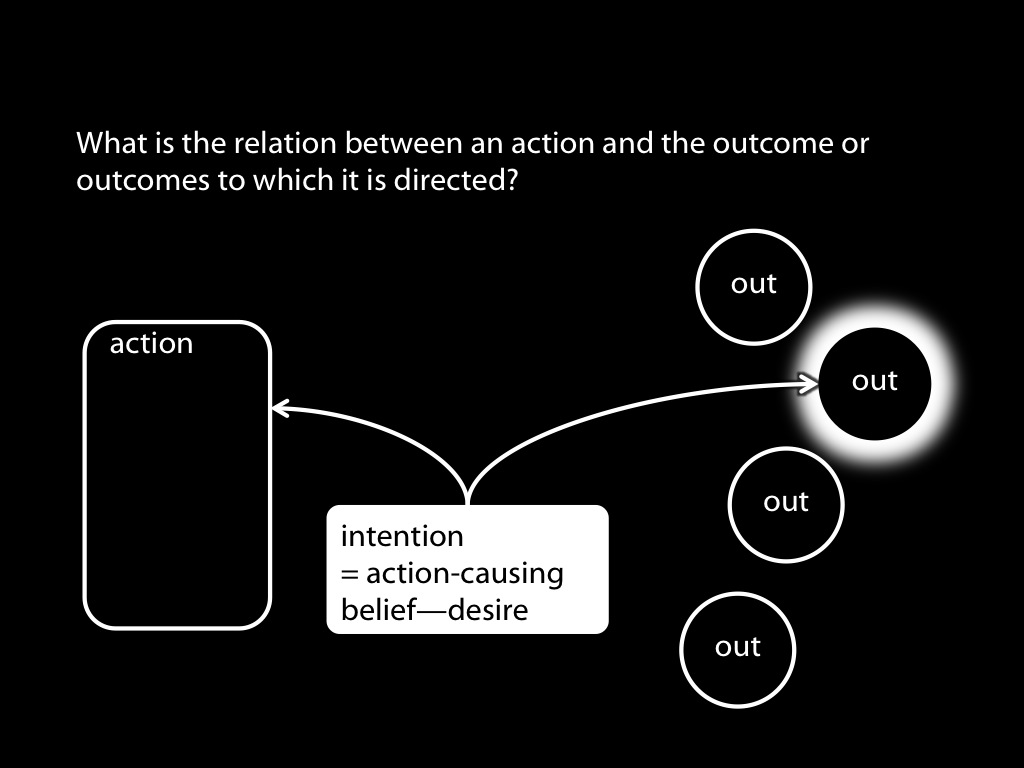

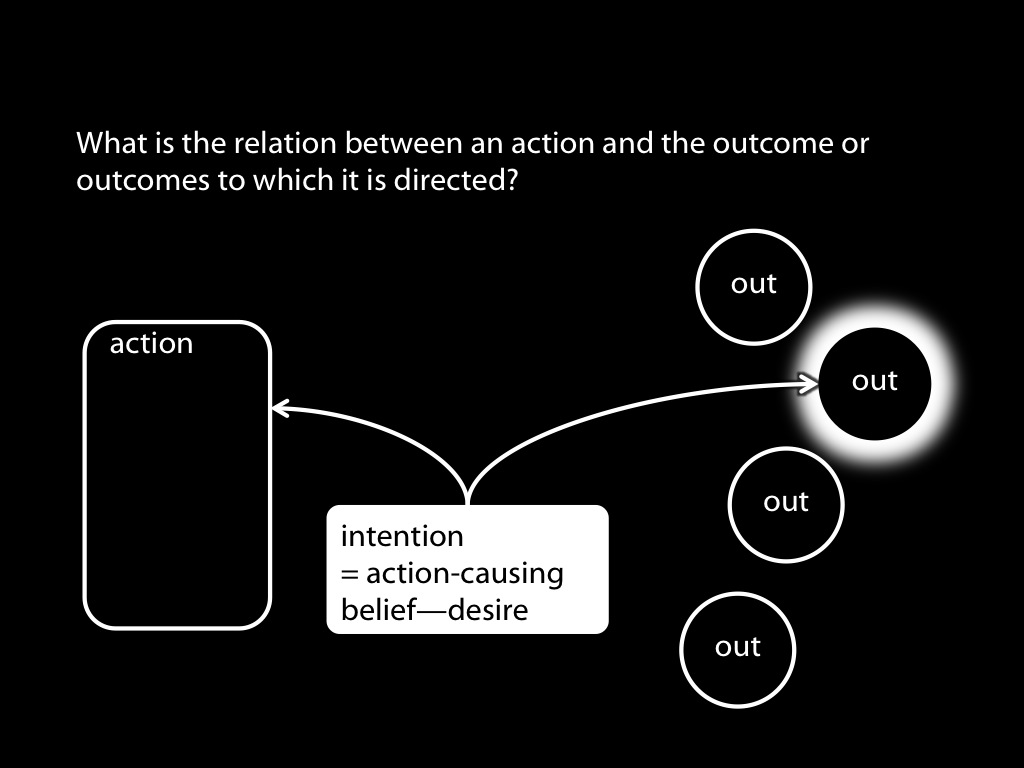

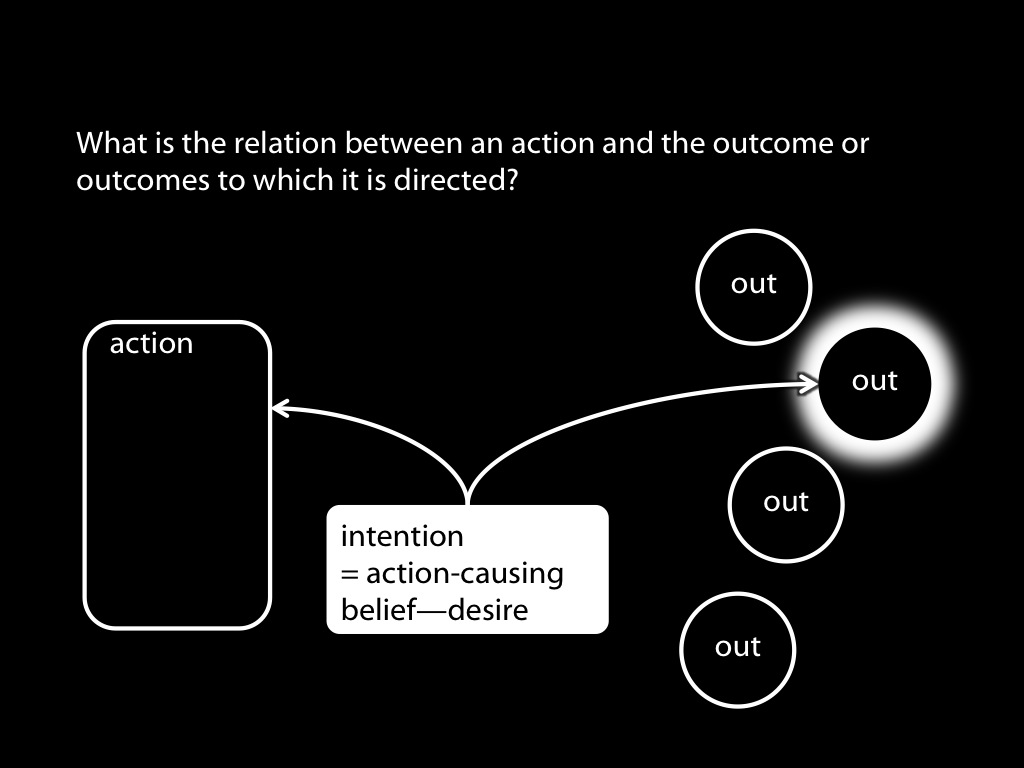

So we have this model of action,

where the relation between an action and a goal exists in virtue of an intention

which represents the goal, coordinates the action, and coordinates the action in such a way

that, normally, the existence of the action increases the probability that the outcome will

occur.

Our question is whether this is infants' model of action.

To answer this question we need first to understand more about the model.

In particular we need to know ...

What is an intention?

[*new route: for the purposes of understanding these agents, we want the simplest possible notion of intention; so we'll take intention as an action-causing belief-desire pair.

The idea I want to consider is, surprisingly, that there are no such things as intentions.

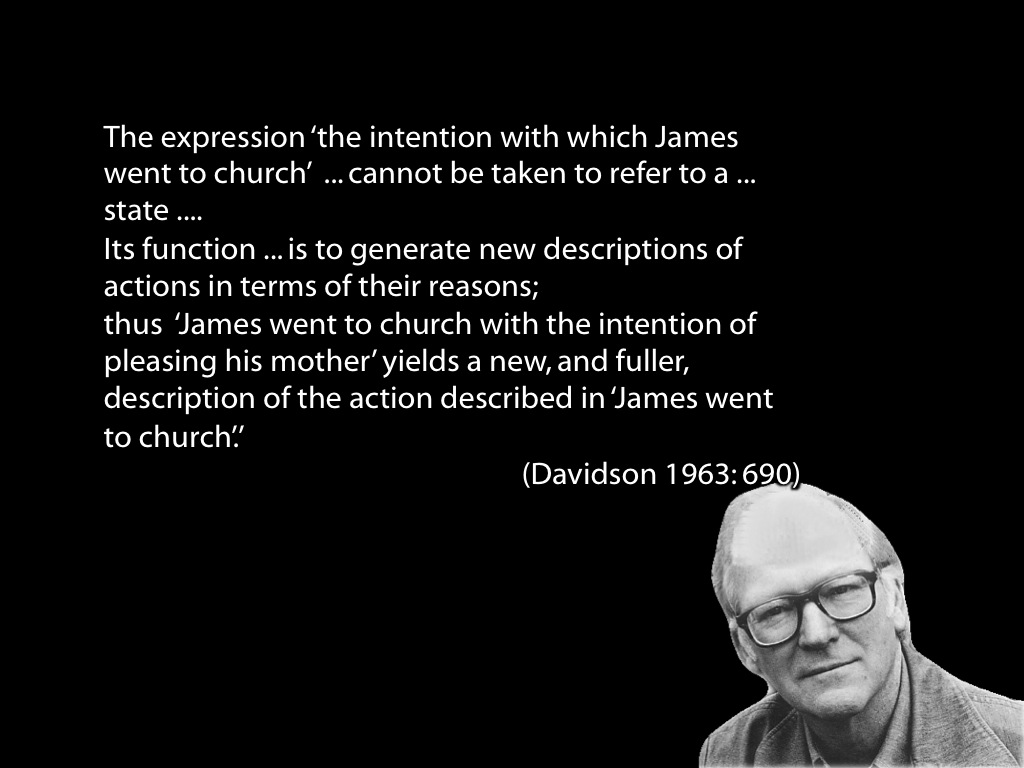

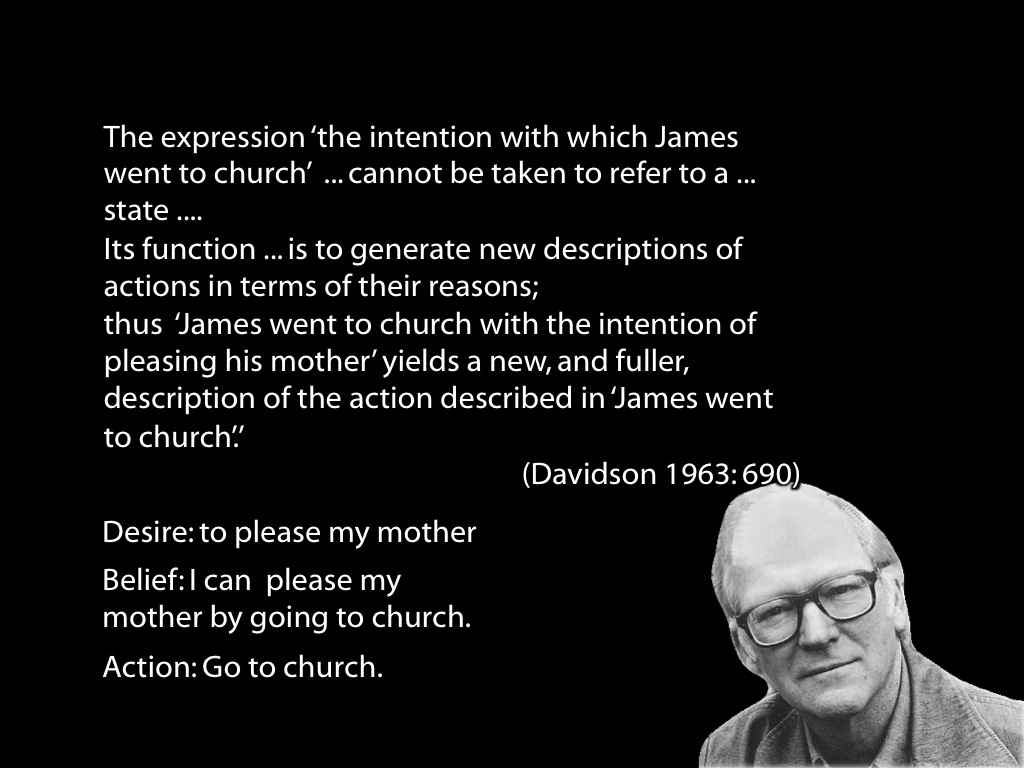

\begin{quote}

`The expression `the intention with which James went to church' has the outward form of a description, but in fact it

...\ % is syncategorematic and

cannot be taken to refer to an entity, state, disposition, or event. Its function in context is to generate new descriptions of actions in terms of their reasons; thus `James went to church with the intention of pleasing his mother' yields a new, and fuller, description of the action described in `James went to church'.'

\citep[p.\ 690]{davidson:1963_orig}

\end{quote}

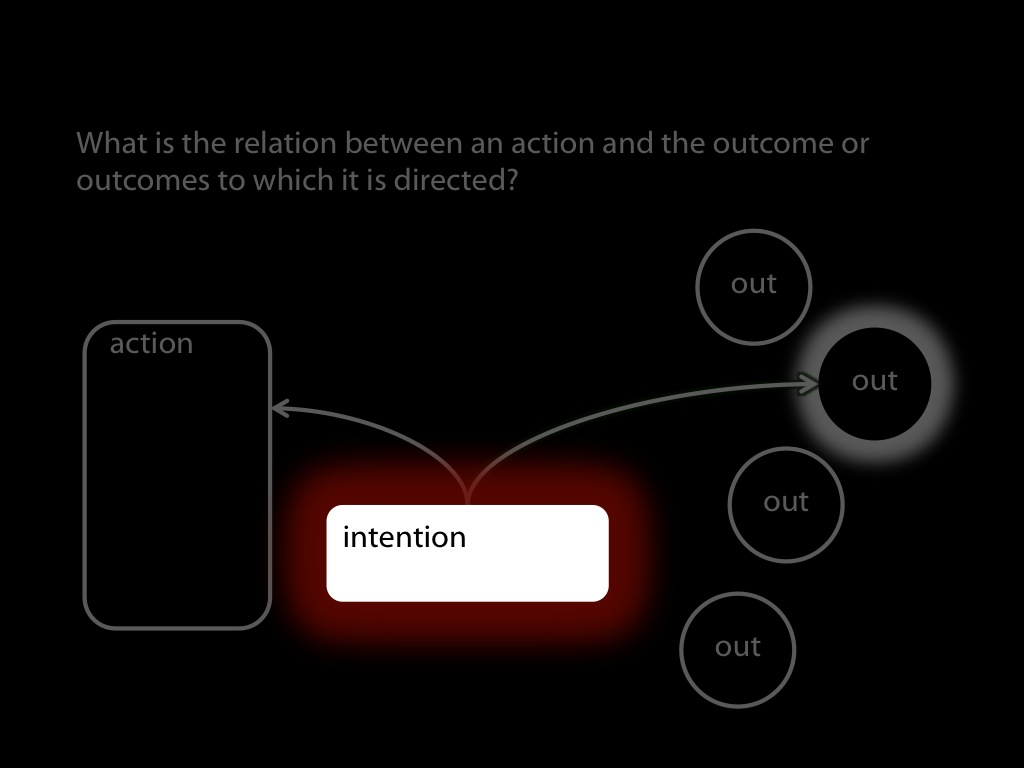

What motivates this view?

We already have beliefs and desires in our model of action explanation.

Introducing intentions as additional mental states would make the model more complicated.

So if we can do without intentions, we should do so in the interests of simplicity.

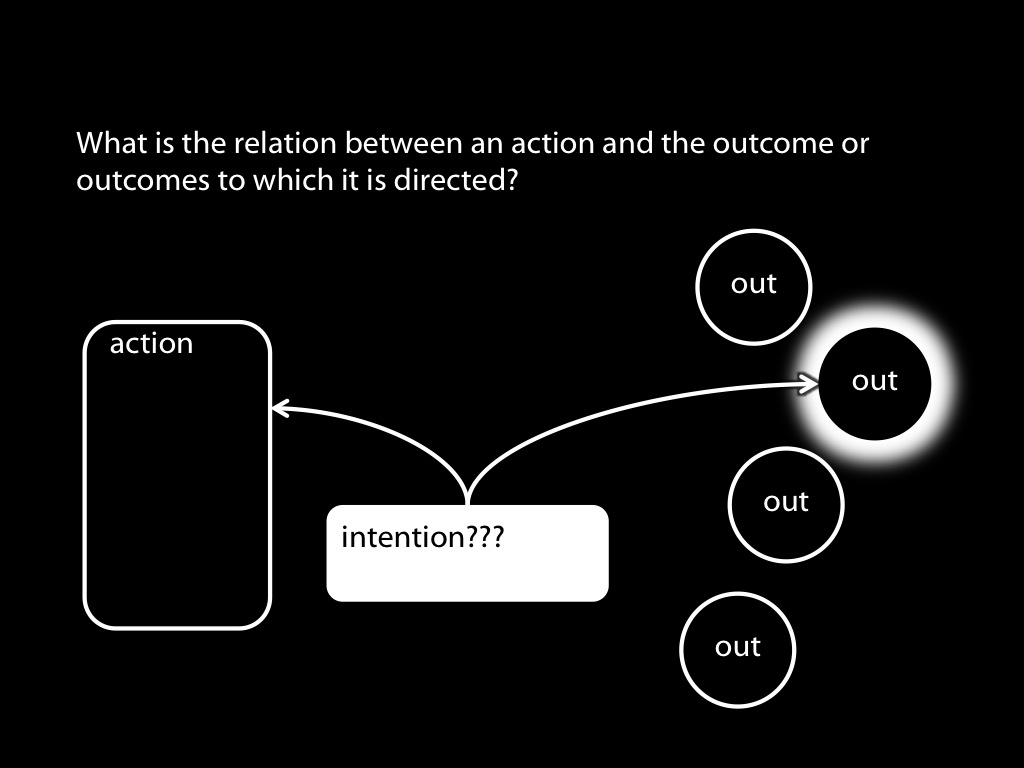

But how can we do without intentions?

Haven't we just seen that we need intentions in order to explain the relation between an action and the goal or goals to which it is directed?

Here's how Davidson's view works.

James desired to please his mother.

James believed that going to church would please his mother.

And this belief and desire caused his going to church.

So the belief--desire pair can play the role of an intention.

It (1) represents an outcome---in this case, the pleasing of James' mother---, (2) causes an event---James' going to church---; and (3) causes an event whose occurrence would normally lead to the outcome’s occurrence.

It appears, then, that we can explain the relation between an action and the goal or goals to which it is directed just in terms of belief and desire.

We don't need to introduce intentions as further mental states.

If we like we can say that an intention just is a suitable, action-causing belief-desire pair.

This view of intention is parallel to a view about knowledge.

Some suppose that knowledge is justified true belief.

Or belief meeting some condition like being true and justified.

On this sort of view, knowledge is not a mental state over and above belief.

Rather, there are just beliefs and some of these beliefs have a special status.

Similarly, Davidson's idea might be put by saying that intentions are just action-causing belief--desire pairs.

(This is not to say that \emph{any} belief--desire pair is an intention, of course.)

Let me give you one more example.

Let's assume that we know what beliefs and desires are.

It's a familiar idea that they combine to cause actions like this:

Belief: that if I don’t comb my hair I will get rabies.

Desire: that I don’t get rabies.

Baldric combed his hair with the intention of avoiding rabies.

To say that he had the intention to avoid rabies is, on this view, just to say that his action was caused by a belief and a desire with these contents.

Now this isn't the right way to model adults' understanding of intention, but it's an approximation that works in the cases we're concerned with.

(Interesting question is why we can’t stop with intention = action-causing belief-desire pair and what intentions are for, but this is a topic for the course about reasons and actions.])

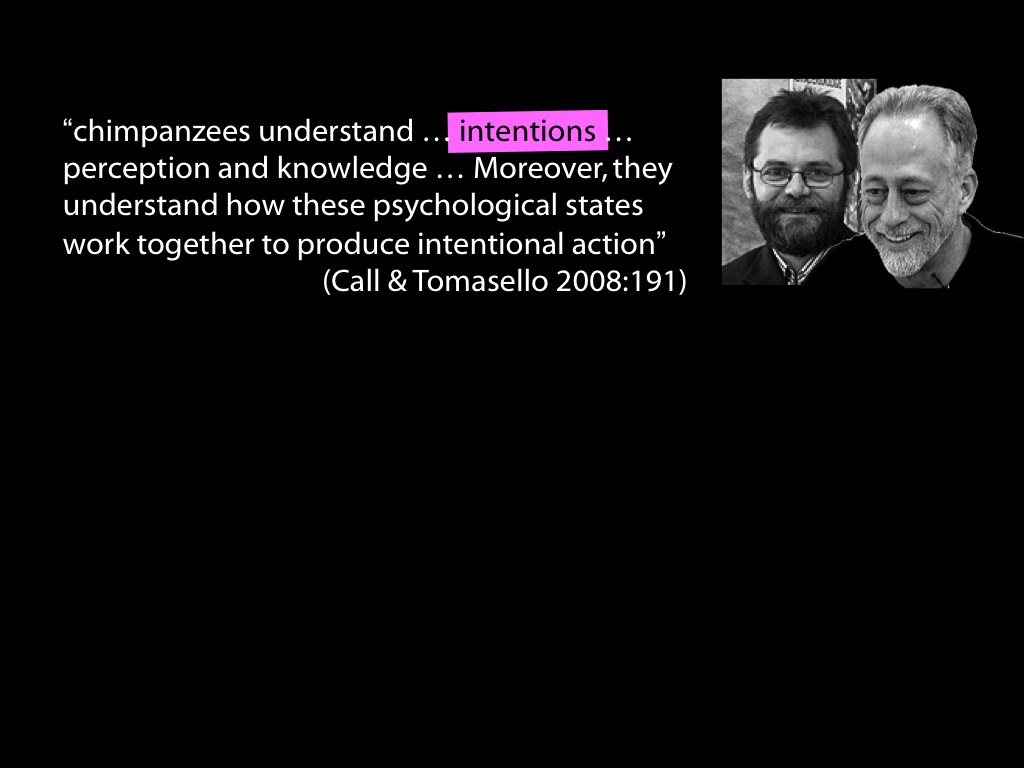

Tomasello and Call say that this *is* the model of action that underpins primate cognition

And we saw earlier that Premack says the same about infants, although not everyone agrees.

‘in perceiving one object as having the intention of affecting another, the infant attributes to the object [...] intentions’

Premack 1990: 14

So should we just stop here?

There are at least three reasons not to stop but rather to look for alternative models of action

...

Reason (a): understanding intention is not something potentially less sophisticated than

understanding belief; on the contrary, even the simplest way of understanding intention

presupposes understanding belief (and desire).

So unless we think infants have a sophisticated understanding of mental states, we shouldn't

suppose that their model of action includes intention.

Reason (b) Minimal theory of mind ... presupposes an understanding of goal-directed action.

If we explain goal-directed action in terms of intention, we are thereby sneaking

beliefs and desire in through the back door. So the whole minimal theory of mind project would

fail.

(You might say, on minimal theory of mind that instead of beliefs and desires we could combine

registration and preference; but that would affect the construction since registration was

explained in terms of goal-directed action).

Reason (c): Mere curiosity. It would be good to see if there is any other, perhaps simpler way

of understanding this relation, perhaps one that doesn't involve insight into mental states.

So, is there a simpler model of the relation, one that infants might understand?