Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Pure Goal Ascription: the Teleological Stance

- What model of action underpins six- or twelve-month-old infants’ abilities to track the goals of actions?

- How could infants identify goals without ascribing intentions?

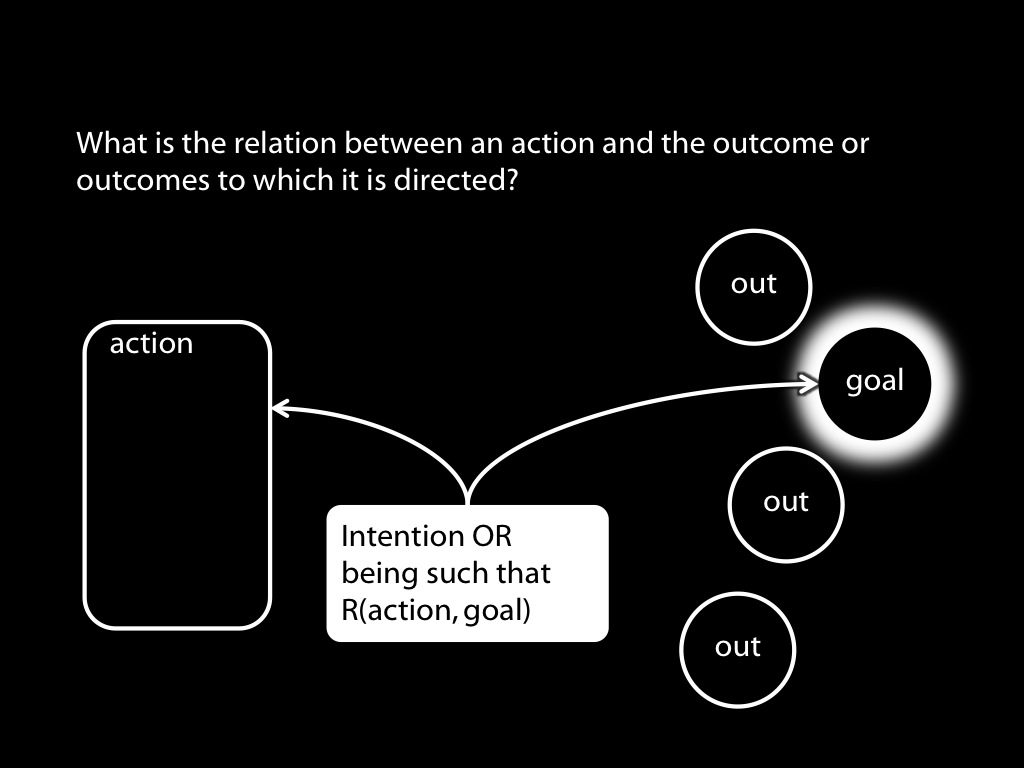

How could pure goal ascription work?

How could pure goal ascription work?

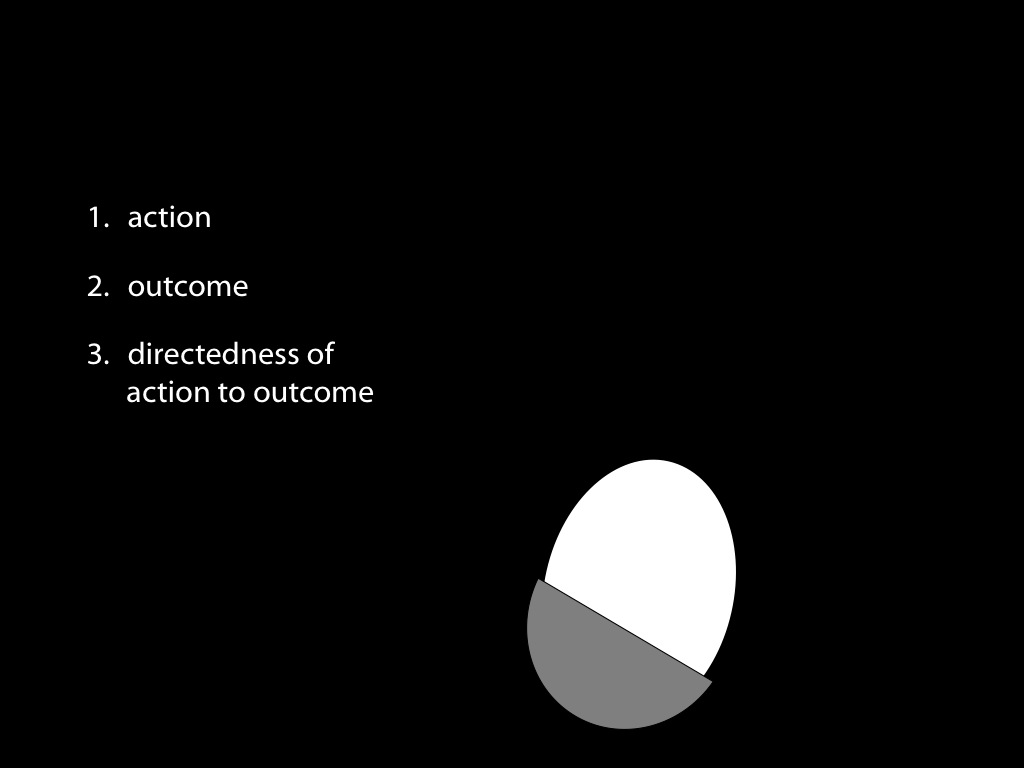

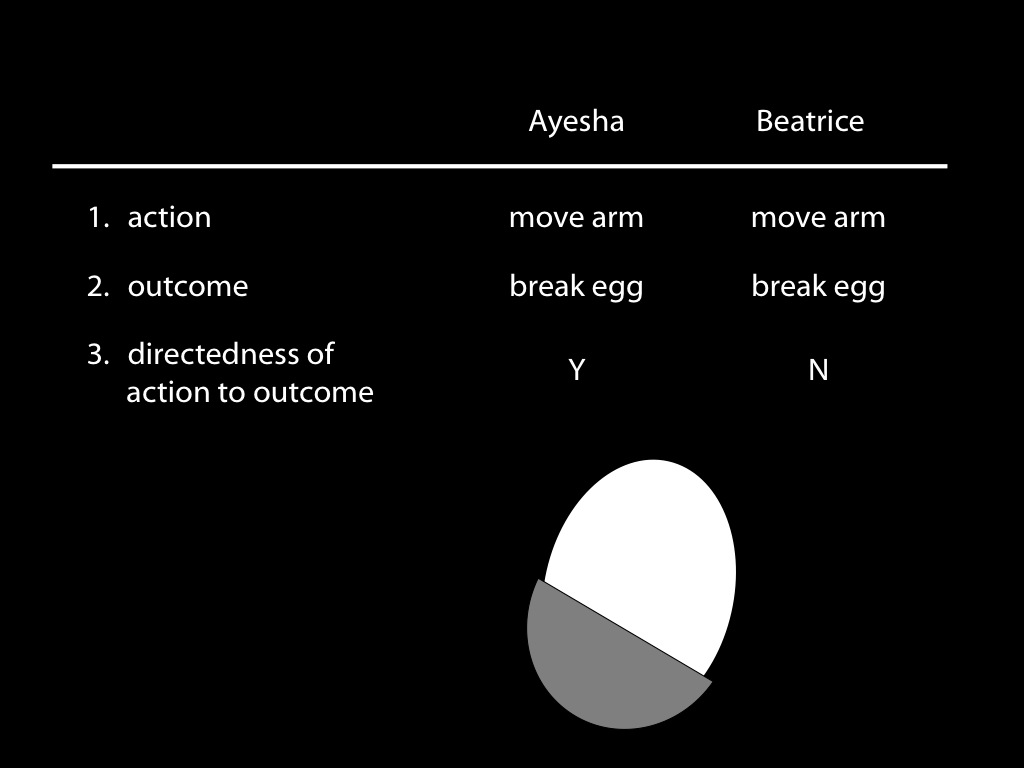

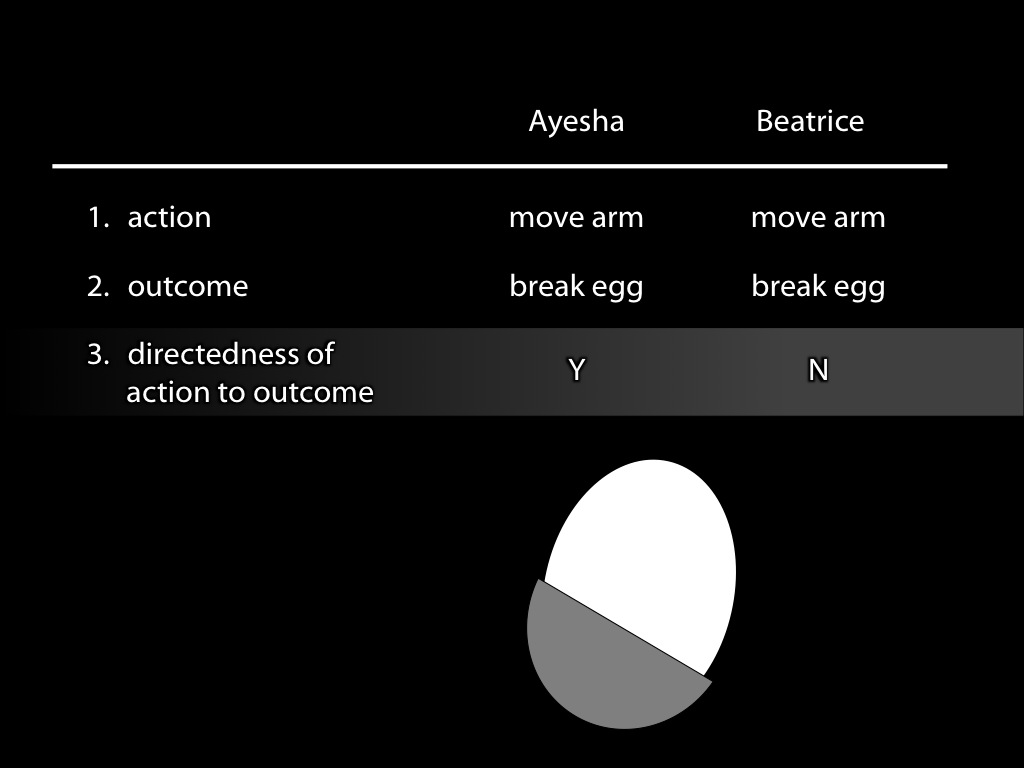

Three requirements ...

- reliably, R(a,G) when and only when a is directed to G

- R(a,G) is readily detectable ...

- ... without any knowledge of mental states

| R(a,G) | =df | a causes G ? |

| R(a,G) | =df | G is a teleological function of a ? |

| R(a,G) | =df | ???a is the most justifiable action towards G available within the constraints of reality |

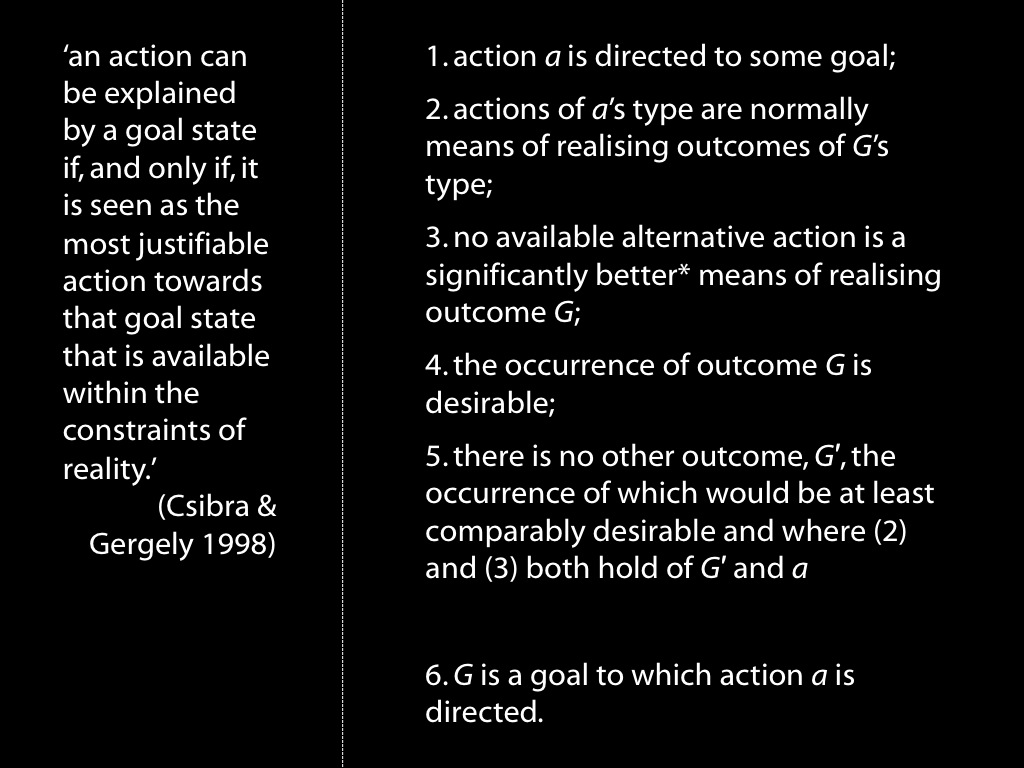

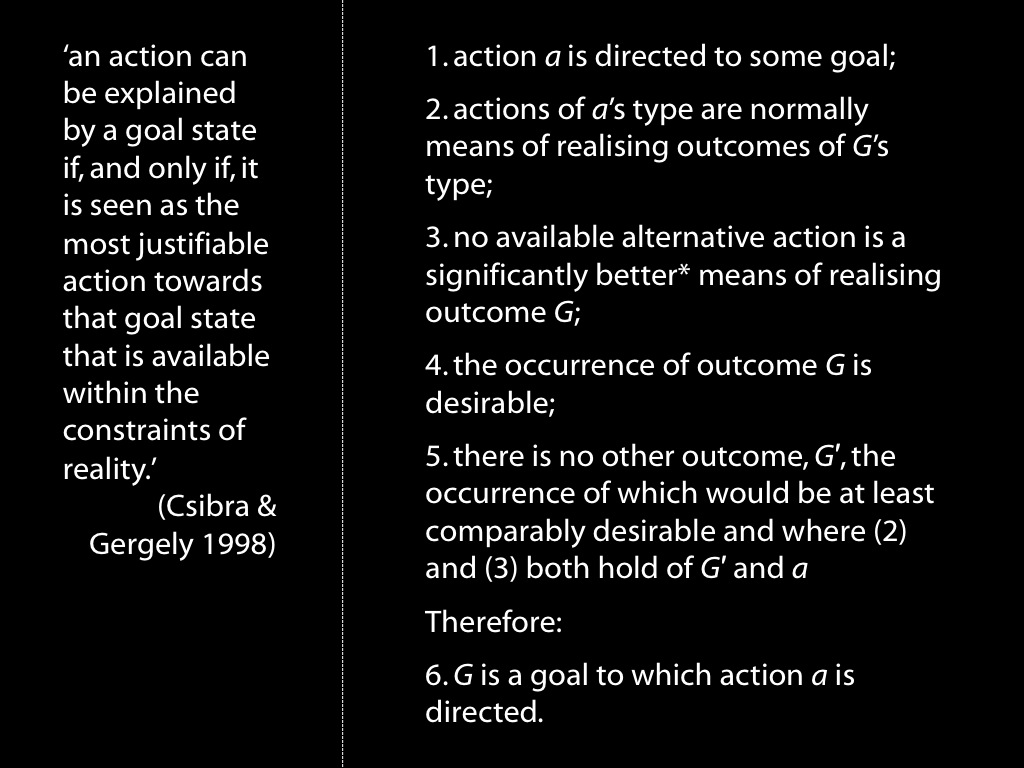

| =df | (1)-(5) are true |

aside: what is a teleological function?

Atta ants cut leaves in order to fertilize their fungus crops (not to thatch the entrances to their homes) \citep{Schultz:1999ps}

‘S does B for the sake of G iff: (i) B tends to bring about G; (ii) B occurs because (i.e. is brought about by the fact that) it tends to bring about G.’ (Wright 1976: 39)

The Atta ant cuts leaves in order to fertilize iff: (i) cutting leaves tends to bring about fertilizing; (ii) cutting leaves occurs because it tends to bring about fertilizing.

‘an action can be explained by a goal state if, and only if, it is seen as the most justifiable action towards that goal state that is available within the constraints of reality’

(Csibra & Gergely 1998: 255)

the teleological stance (Gergely & Csibra)

`Such calculations require detailed knowledge of biomechanical factors that determine the motion capabilities and energy expenditure of agents. However, in the absence of such knowledge, one can appeal to heuristics that approximate the results of these calculations on the basis of knowledge in other domains that is certainly available to young infants. For example, the length of pathways can be assessed by geometrical calculations, taking also into account some physical factors (like the impenetrability of solid objects). Similarly, the fewer steps an action sequence takes, the less effort it might require, and so infants’ numerical competence can also contribute to efficiency evaluation.’

Csibra & Gergely (forthcoming ms p. 8)

summary so far

How could pure goal ascription work?

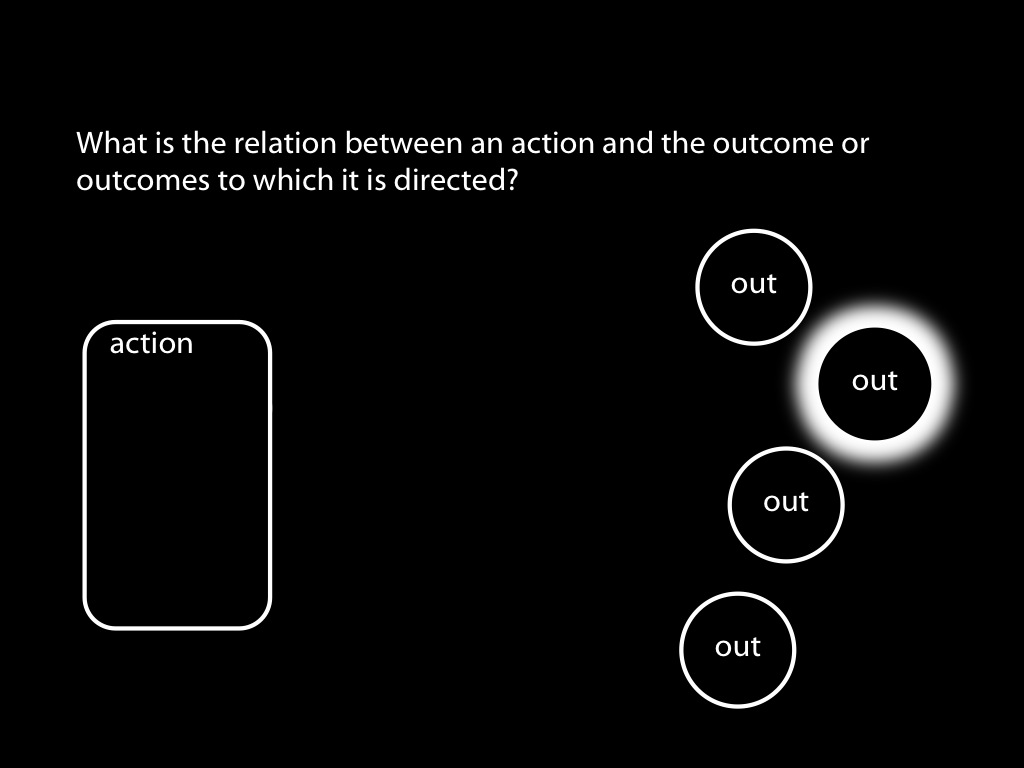

R(a,G) = ???

teleological stance

problem: detecting optimality

a solution?

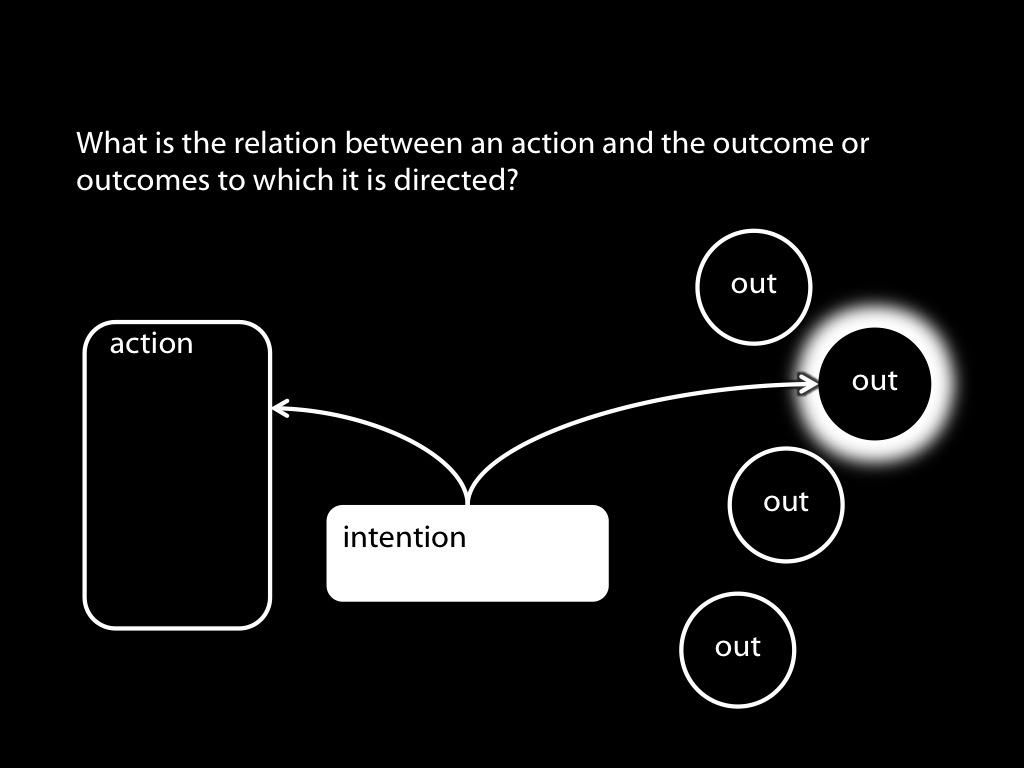

goal ascription is acting in reverse

-- in action observation, possible outcomes of observed actions are represented

-- these representations trigger planning as if performing actions directed to the outcomes

-- such planning generates predictions

-- a triggering representation is weakened if its predictions fail

- reliably, R(a,G) when and only when a is directed to G

- R(a,G) is readily detectable ...

- ... without any knowledge of mental states

| R(a,G) | =df | a is the most justifiable action towards G available within the constraints of reality |

| RM(a,G) | =df | if M were tasked with producing G it would plan action a |

‘when taking the teleological stance one-year-olds apply the same inferential principle of rational action that drives everyday mentalistic reasoning about intentional actions in adults’

(György Gergely and Csibra 2003; cf. Csibra, Bíró, et al. 2003; Csibra and Gergely 1998: 259)

- What model of action underpins six- or twelve-month-old infants’ abilities to track the goals of actions?

- How could infants identify goals without ascribing intentions?

(I.e., How could pure goal ascription work?)

Answer: goal ascription is acting in reverse

| RM(a,G) | =df | if M were tasked with producing G it would plan action a |

‘What it is to be a true believer is to be … a system whose behavior is reliably and voluminously predictable via the intentional strategy.’

Dennett 1987, p. 15

An outcome, G, is among the goals of an action, a, exactly if RM(a,G)