Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Origins of Mind

Lecture 03

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk

two interlocking themes:

- the problem

- knowledge of causal interactions

infant

adult

social interaction

language

time --->

Perception of Causation

Can humans perceive causal interactions?

Thines et al (1991)

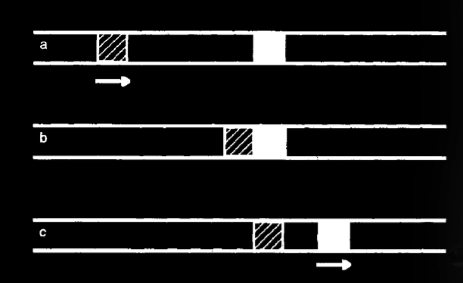

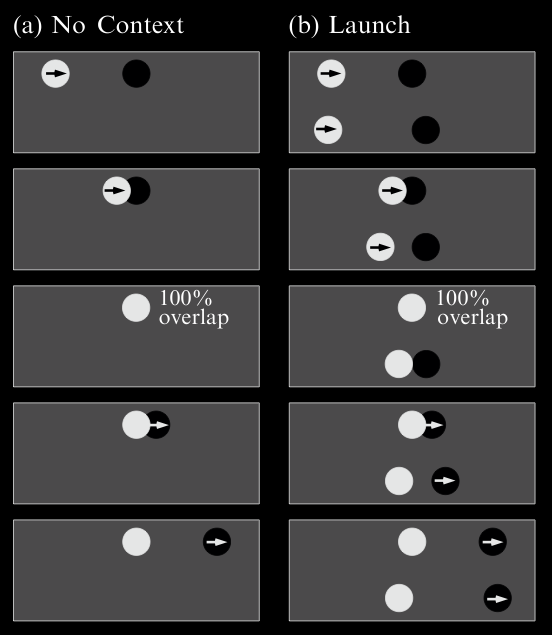

Scholl & Tremoulet 2001, figure 2

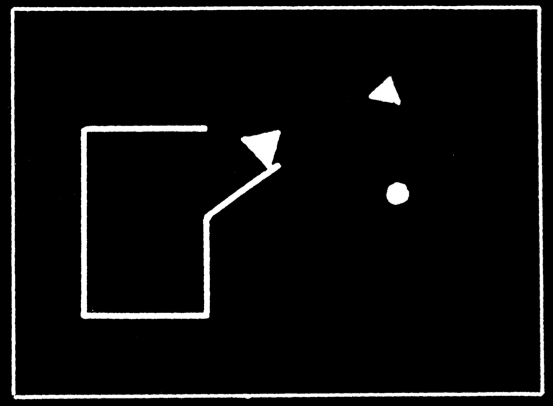

Heider & Simmel 1946, figure 1

How to get beyond intuition?

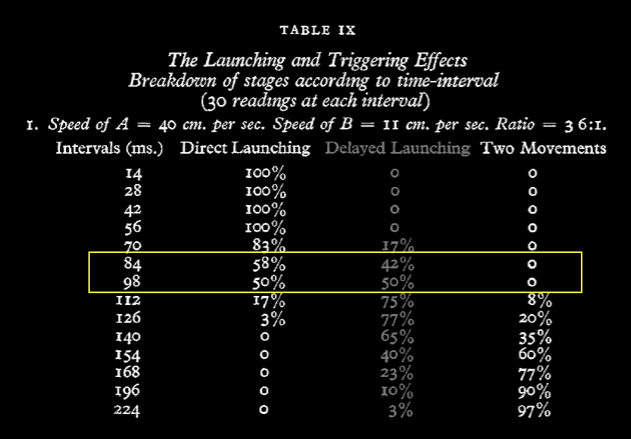

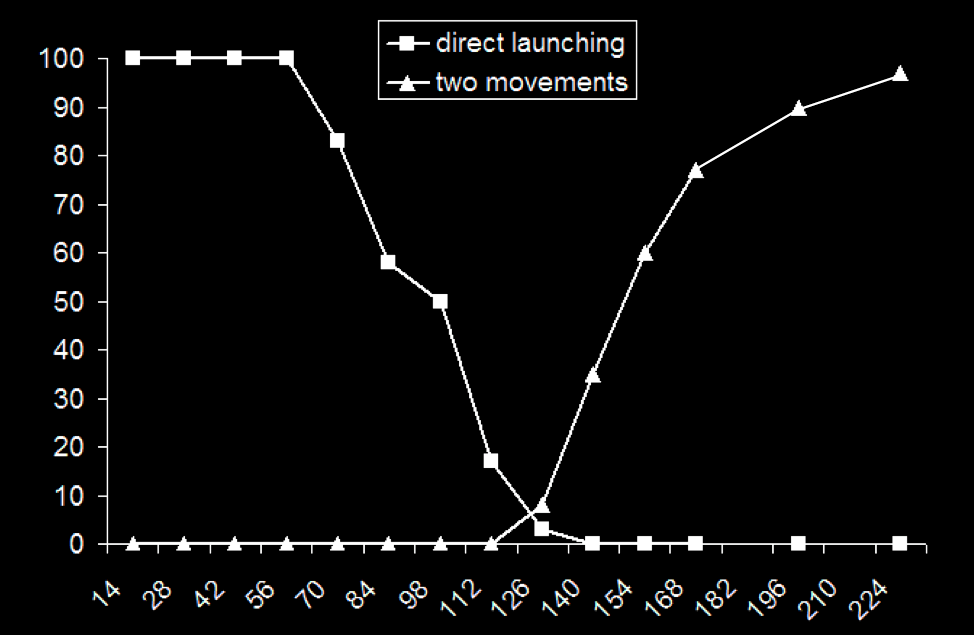

Michotte: the experience of launching depends on interactions among various factors including

- the relative speeds of the two objects

- the delay between the first and second objects’ movements

- the spatial gap between the two objects

- the trajectories of the two objects.

Michotte 1946 [1963], p. 115 table IX (part)

Michotte 1946 [1963], p. 115 table IX (part)

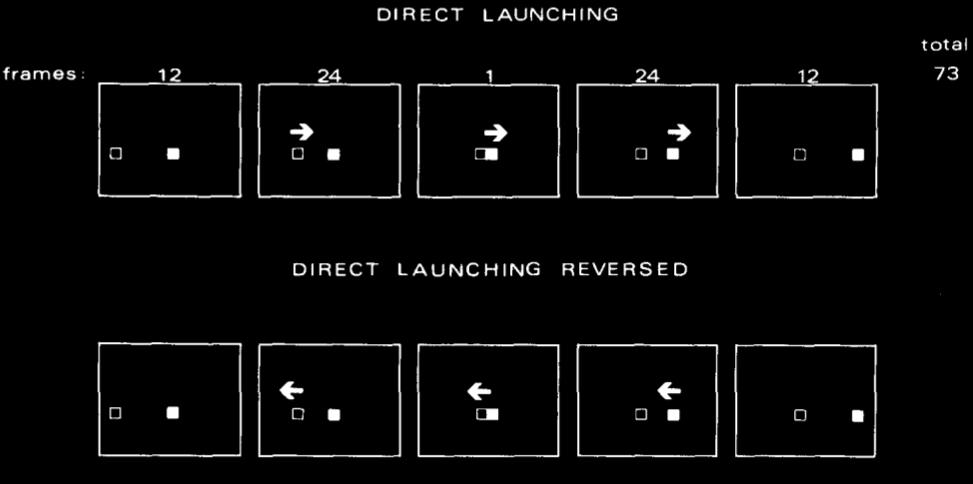

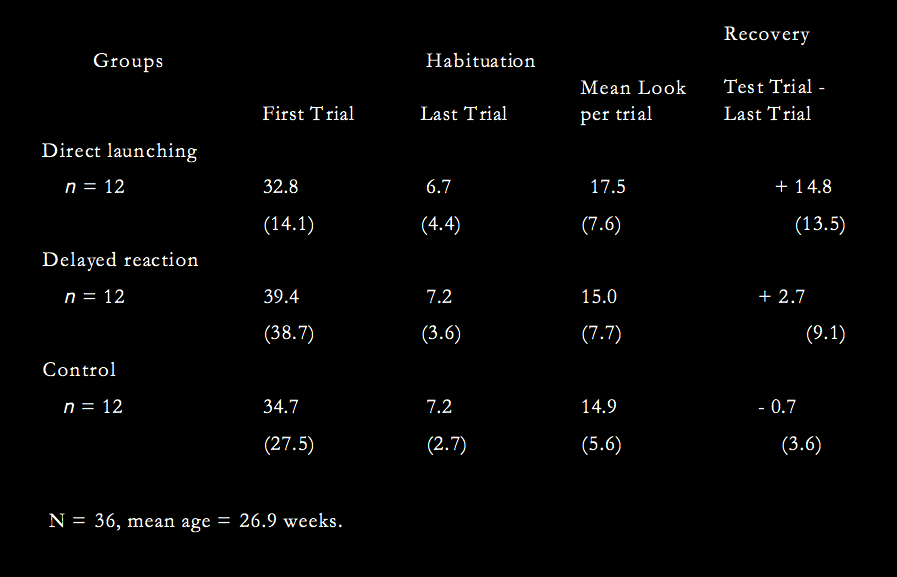

detecting launching effects at 6 months

Leslie & Keeble 1987, figure 4

Leslie & Keeble 1987, table 4

How to get beyond intuition?

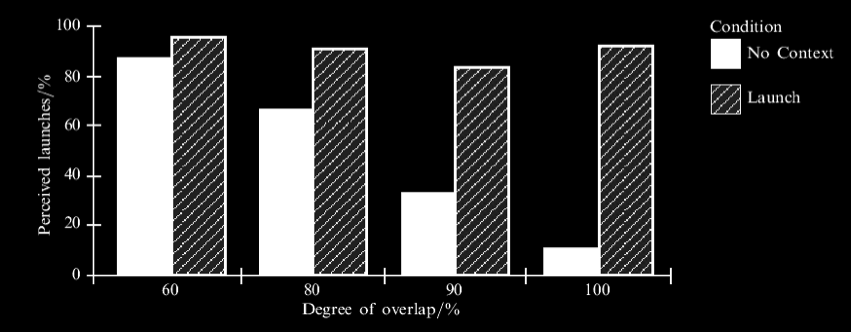

The launching effect: detecting a 50ms difference in the delay between two movements.

- How is launching detected? For example, does it involve perceptual processes?

- Why is a delay of up to around 70ms consistent with the launching effect occuring?

Guess how the launching effect works!

judgement-independent

Thines et al (1991)

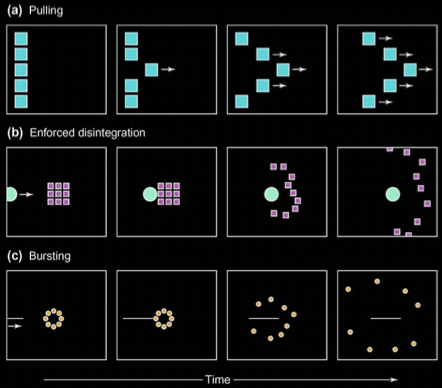

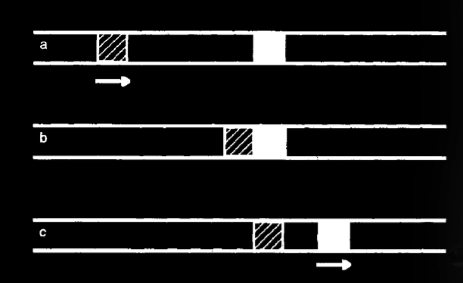

Scholl and Nakayama 2004, figure 2 (part)

Scholl and Nakayama 2004, figure 5

- How is launching detected? For example, does it involve perceptual processes?

- Why is a delay of up to around 70ms consistent with the launching effect occuring?[This question is blurred]

Summary so far

- Adults report experiencing a launching effect.

- These reports show that they can make minute distinctions.They can detect tiny, 50 millisecond differences in the delay between two movements.

- Infants detect apparent causal interactions from 6 months of age or earlier.

- Detecting apparent causal interactions is bound up with perceiving objects.It's not that we first perceive objects and surfaces, and then identify causal interactions. Rather, identifying causal interactions is part of perceiving surfaces and objects. So the launching effect does seem to involve perceptual processes.

Object Indexes and Causal Interactions

Attention to Objects

Pylyshyn 2001, figure 6

object index (/ FINST)

object indexes require segmentation

object indexes can survive occlusion

object indexes require tracking some causal interactions ...

- How is launching detected? For example, does it involve perceptual processes?

- Why is a delay of up to around 70ms consistent with the launching effect occuring?

‘anyone not very familiar with the procedure involved in framing the physical concepts of inertia, energy, conservation of energy, etc., might think that these concepts are simply derived from the data of immediate experience.’

\citep[p.\ 223]{Michotte:1946nz}Michotte (1946, p. 223)

Can humans perceive causal interactions?

Perceptual systems identify certain kinds of causal interaction in the course of tracking objects.

further evidence

object-specific preview effect

Kahneman et al 1992, figure 3

Causal interactions are detected by the perceptual processes involved in segmenting and tracking objects.

Object Indexes and the Principles of Object Perception

Three requirements

- segment objects

- represent objects as persisting

- track objects’ interactions

Principles of Object Perception

- cohesion

- boundedness

- rigidity

- no action at a distance

(Spelke 1990)

the Simple View

The principles of object perception

are not items of knowledge

instead

they characterise the operation of

object-indexes (aka FINSTs, mid-level object files)

Leslie et al (1989); Scholl and Leslie (1999); Carey and Xu (2001)

‘if you want to describe what is going on in the head of the child when it has a few words which it utters in appropriate situations, you will fail for lack of the right sort of words of your own.

‘We have many vocabularies for describing nature when we regard it as mindless, and we have a mentalistic vocabulary for describing thought and intentional action; what we lack is a way of describing what is in between’

(Davidson 1999, p. 11)

The principles of object perception

are not items of knowledge

instead

they characterise the operation of

object-indexes (aka FINSTs, mid-level object files)

Leslie et al (1989); Scholl and Leslie (1999); Carey and Xu (2001)

infant

adult

social interaction

language

time --->

Perceptual Expectations

Infants have expectations, but what about adults?

Michotte et al (1964) via Kellman and Spelke (1983, figure 2)

representational momentum

Freyd and Jones 1994, figure 1

Kozhevnikov and Hegarty 2001, figure (from appendix)

signature limits

infant

adult

social interaction

language

time --->

Summary of Lecture 03

two interlocking themes:

- the problem

- knowledge of causal interactions

- Can humans perceive causal interactions?

The Next Big Problem