Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Origins of Mind

Lecture 05

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk

Our Next Big Problem

social interaction

Communication with Words: A Question

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

‘the topic of successful communication in the actual world is far too complex and obscure’

(Chomsky 1992: 120)

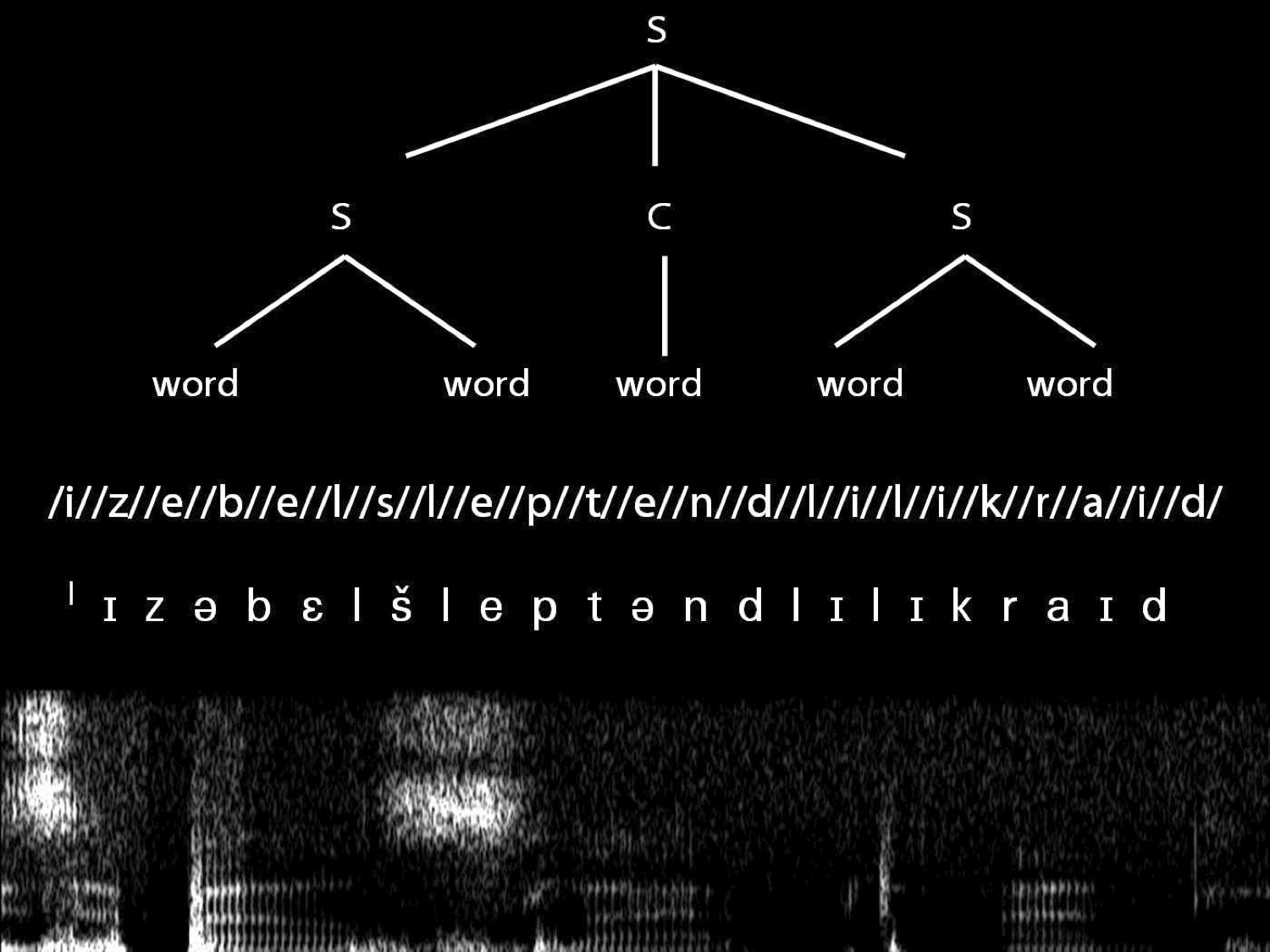

What are the components of an utterance?

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

Preview: Shipwreck Survivor vs Lab Rat

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

Two models:

- shipwreck survivor

- lab rat

shipwreck survivor:

‘children learn words through the exercise of reason’ (\citealp[p.\ 1103]{Bloom:2001ka}; see \citealp{Bloom:2000qz})

(Bloom 2001, p. 1103)

‘Augustine describes the learning of human language as if the child came into a strange country and did not understand the language of the country; that is, as if it already had a language, only not this one. Or again: as if the child could already think, only not yet speak.’

(Wittgenstein 1953, p. 15--16, §32)

‘[t]he child learns this language from the grown-ups by being trained to its use. I am using the word ‘trained’ in a way strictly analogous to that in which we talk of an animal being trained to do certain things. It is done by means of example, reward, punishment, and suchlike’

(Wittgenstein 1972, p. 77).

‘the child’s early learning of a verbal response depends on society's reinforcement of the response in association with the stimulations that merit the response’

(Quine 1960, p. 82)

‘A child learning to speak is learning habits and associations which are just as much determined by the environment as the habit of expecting dogs to bark and cocks to crow’

(Russell 1921, p. 71).

social interaction

children create and creatively adapt words before (and after) learning those of the adults around them

INVESTIGATOR: what is that called?

SHEM: dat's uh vam.

INVESTIGATOR: a vam?

SHEM: yeah.

INVESTIGATOR: why is it called a vam?

SHE: it vams all duh room ups all the water up ...

source: Eve Clark's CHILDES data

(Clark 1982; MacWhinney 2000)

Children with no experience of others' languages can create their own languages.

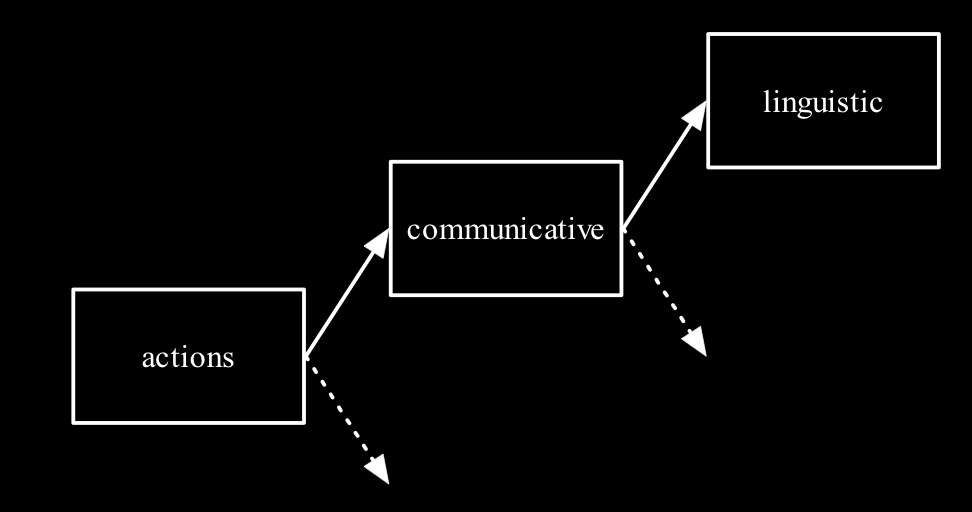

Language acquisition is neither merely a matter of training, nor merely a matter of reasoning about the meanings of words. Rather, it involves social interaction from the first utterances of words.

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

outline:

- the lab rat

- why the lab rat view is wrong

- the shipwreck survivor

- why the shipwreck survivor is wrong

- a problem

Does being able to think depend on being able to communicate with language?

- If someone can think, she must be capable of having a false belief.

- To be capable of having a false belief it is necessary to understand the possibility of false belief.

- Understanding the possibility of false belief entails being able to communicate by language.

Conclusion:

If someone can think, she can communicate with language.

‘We, observing and describing … a creature …, say that it discriminates certain shapes, objects, colors, and so forth, by which we mean that it reacts in ways we find similar to shapes, objects, and colors which we find similar.

But we would be making a mistake if we were to assume that because the creature discriminates and reacts in much the way we do, that it has the corresponding concepts.

The difference, as I keep emphasizing, lies in the fact that we, unlike the creature I am describing, can, from our point of view, make mistakes in classification.’

Davidson (2001: 11)

‘We, observing and describing … a creature …, say that it discriminates certain shapes, objects, colors, and so forth, by which we mean that it reacts in ways we find similar to shapes, objects, and colors which we find similar.

But we would be making a mistake if we were to assume that because the creature discriminates and reacts in much the way we do, that it has the corresponding concepts.

The difference, as I keep emphasizing, lies in the fact that we, unlike the creature I am describing, can, from our point of view, make mistakes in classification.’

Davidson (2001: 11)

- If someone can think, she must be capable of having a false belief.

- To be capable of having a false belief it is necessary to understand the possibility of false belief.

- Understanding the possibility of false belief entails being able to communicate by language.

Conclusion:

If someone can think, she can communicate with language.

‘we grasp the concept of truth only when we can communicate the contents---the propositional contents---of the shared experience, and this requires language’

Davidson 1997, p. 27

‘the process of language acquisition [is] coming to know the meanings of words, where at a given stage the learner’s conception is an hypothesis about the meaning’

Higginbotham 1998, p. 153

two directions

-

If someone can think, she can communicate with language.

- Acquiring language involves thinking from the start.

If 1, then not 2.

If 2, then not 1.

Training

‘The ability to discriminate, to act differentially in the face of clues to the presence of food, danger or safety, is present in all animals and does not require reason. Nor does the learning, even of complex routines, require reason, for it is possible to learn how to act without learning that anything is the case.’

Davidson (1982b, 326); cf. (1995c, 207)

‘A child learning to speak is learning habits and associations which are just as much determined by the environment as the habit of expecting dogs to bark and cocks to crow’

(Russell 1921, p. 71)

‘[t]he child learns this language from the grown-ups by being trained to its use. I am using the word ‘trained’ in a way strictly analogous to that in which we talk of an animal being trained to do certain things. It is done by means of example, reward, punishment, and suchlike’

(Wittgenstein 1972, p. 77).

‘the child’s early learning of a verbal response depends on society's reinforcement of the response in association with the stimulations that merit the response’

(Quine 1960, p. 82)

infant

stimulations -> utter 'nana'

rat

stimulations -> press lever

‘there is a rudiment of communication in the simple discovery that sounds produce results. Crying is the first step toward language when crying is found to procure one or another form of relief or satisfaction. More specific sounds, imitated or not, are rapidly associated with more specific pleasures.

‘A large further step has been taken when the child notices that others also make distinctive sounds at the same time the child is having the experiences that provoke its own volunteered sounds. For the adult, these sounds have a meaning, perhaps as one word sentences. The adult sees herself as doing a little ostensive teaching: “Eat,” “Red,” “Ball,” “Mamma,” “Milk,” “No.” There is now room for what the adult views as error: the child says “Block” when it is a slab. This move fails to be rewarded, and the conditioning becomes more complex’

(Davidson 2000: 70-1; see also Davidson 1999: 11).

Understanding

What do I know or understand when I can communicate with language?

‘You can deceive yourself into thinking that the child is talking if it makes sounds which, if made by a genuine language-user, would have a definite meaning.

’ … If a mouse had vocal cords of the right sort, you could train it to say “Cheese”. But that word would not have a meaning when uttered by the mouse, nor would the mouse understand what it “said”.’

Davidson 1999: 11

'to attribute to a speaker no more than knowledge of how to play … interlocking language games is to make him a participant in an activity he cannot survey (‘cannot see what is going on’).'

Dummett (1979: 224)

Understanding a word can’t be purely a practical ability because this would ‘render mysterious our capacity to know whether we are understanding.’

Dummett (1991: 93)

Language is ‘a rational activity on the part of creatures to whom can be ascribed intention and purpose’. So we need to distinguish ‘those regularities of which a language speaker, acting as a rational agent engaged in conscious, voluntary action, makes use from those that may be hidden from him.’

Dummett (1978: 104)

‘A child at this stage has no linguistic knowledge but merely a training in certain linguistic practices. When he has reached a stage at which it is possible for him to lie, his utterances will have ceased to be merely responses to features of his environment or to experienced needs. They will have become purposive actions based upon a knowledge of their significance to others.’

Dummett (1991:95)

- Communicating with language involves being able to understand what you've said.

- Being trained in how words are used does not enable one to understand what would be said in uttering those words.

Conclusion:

We cannot fully explain how humans become able to communicate with language by appeal to training.

‘Whenever I think I understand what he [Davidson] is trying to say, I am told by the Davidson scholars that it is all much more subtle and interesting than that, though very difficult to articulate except by quoting more Davidson.’

Gopnik, “How to understand beliefs” (1995: 399)

Creativity

recap

Assumption:

If someone can communicate with language, she can think.

Consequence:

Acquiring language cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Question:

How could someone begin to acquire words without being able to think?

Answer:

By being trained to utter a particular word in response to certain simulations!

Observation:

There is a gap between what training achieves (use) and what language acquisition requires (understanding).

Now:

How do children actually acquire language?

homesigns

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 1)

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 2)

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 11)

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 22)

Gesture forms are:

- stable

- arbitrary

- systematic

Gesture forms are used:

- with different forces (to ask questions, make comments, request things, ...)

- to talk about past, future and hypothetical things

- to tell stories

- to communicate with oneself

- to talk about gestures (metalanguage)

Goldin-Meadow 2002

Children can create their own first languages.

recap

Assumption:

If someone can communicate with language, she can think.

Consequence:

Acquiring language cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Question:

How could someone begin to acquire create words without being able to think?

Answer:

By being trained to utter a particular word in response to certain simulations!

Observation:

There is a gap between what training achieves (use) and what language acquisition requires (understanding).

Now:

How do children actually acquire language?

aside

- If someone can think, she must be capable of having a false belief.

- To be capable of having a false belief it is necessary to understand the possibility of false belief.

- Understanding the possibility of false belief entails being able to communicate by language.

Conclusion:

If someone can think, she can communicate with language.

‘Intentional action cannot emerge before belief and desire, for an intentional action is one explained by beliefs and desires that caused it.’

Davidson 1999, p. 10

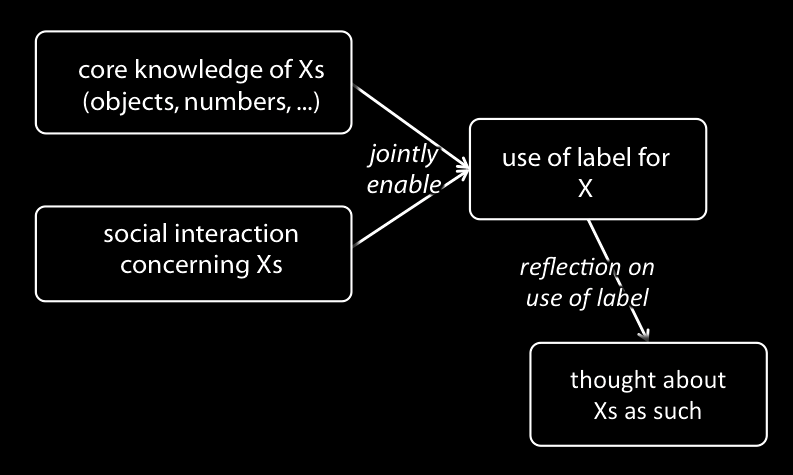

Mapping words to concepts

fresh start (the shipwreck survivor)

‘children learn words through the exercise of reason’ (\citealp[p.\ 1103]{Bloom:2001ka}; see \citealp{Bloom:2000qz})

Bloom 2001, p. 1103

‘much of what goes on in word learning is establishing a correspondence between the symbols of a natural language and concepts that exist prior to, and independently of, the acquisition of that language’

Bloom 2000, p. 242

‘to know the meaning of a word is to have:

1. a certain mental representation or concept

2. that is associated with a certain form’

Bloom 2000, p. 17

‘Augustine describes the learning of human language as if the child came into a strange country and did not understand the language of the country; that is, as if it already had a language, only not this one. Or again: as if the child could already think, only not yet speak.’

(Wittgenstein 1953, p. 15--16, §32)

'The tutor names things in accordance with the semantic customs of the community. The player forms hypotheses about the categorical nature of the things named. He tests his hypotheses by trying to name new things correctly. The tutor compares the player's utterances with his own anticipations of such utterances and, in this way, checks the accuracy of fit between his own categories and those of the player. He improves the fit by correction.'

Brown (1958, p. 194) as quoted by Clark (1993, p. 19)

Assumption:

If someone is in a position to learn a word, she already has the corresponding concept

Consequence:

Learning words cannot ever be a route to acquiring concepts.

Case study:

Kowalski and Zimilies on colour terms and concepts.

‘much of what goes on in word learning is establishing a correspondence between the symbols of a natural language and concepts that exist prior to, and independently of, the acquisition of that language’

Bloom 2000, p. 242

‘One of the first problems children take on is the MAPPING of meanings onto forms … They must identify possible meanings, isolate possible forms, and then map the meanings onto the relevant forms.’

Clark 1993, p. 14

‘puttaputta’

June, age 1;3.0

JUNE: puttaputta.

MOTHER: puttaputta … ok.

MOTHER: this puttaputta?

MOTHER: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickle peppers […]

[…]

JUNE: puttaputta.

MOTHER: puttaputta?

MOTHER: where's puttaputta?

MOTHER: can you show me puttaputta?

June turns the page.

[…]

JUNE: puttaputta.

MOTHER: that's not puttaputta.

Roy Higginson's CHILDES data (1985)

JUNE: puttaputta.

MOTHER: puttaputta?

JUNE: puttaputta.

MOTHER: ok … Doctor .

June takes the book, looks at it and the hands it back to her mother.

MOTHER: Foster went to Gloucester in a shower of rain … he stepped into a puddle right up to his middle and never went there again.

JUNE: puttaputta.

MOTHER: ok … the late Madame Fry wore shoes a mile high and when she walked by me I thought I should die.

Roy Higginson's CHILDES data (1985)

JUNE: putta .

JUNE: puttaputta .

MOTHER: am I supposed to read that ?

MOTHER: you have to come over here then .

JUNE: puttaputta .

MOTHER: what do you want me to puttaputta ?

MOTHER: what's this ?

JUNE: car ?

Roy Higginson's CHILDES data (1985)

‘children learn words through the exercise of reason’

Bloom 2001, p. 1103

‘much of what goes on in word learning is establishing a correspondence between the symbols of a natural language and concepts that exist prior to, and independently of, the acquisition of that language’

Bloom 2000, p. 242

‘to know the meaning of a word is to have:

1. a certain mental representation or concept

2. that is associated with a certain form’

Bloom 2000, p. 17

Summary

How do humans first come to communicate with words?

Assumption:

If someone can think, she can communicate with language

Consequence:

Acquiring a language cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Problem:

Humans can make the transition from to communicating with language by creating their own language.

Aside:

Becoming able to communicate with language does not always involve being trained or shown.

What do I know when I can communicate with words?

word-concept mappings

How do I come to know word-concept mappings?

‘through the exercise of reason’ (Bloom 2001, p. 1103)

Consequence:

Learning words cannot be a route to acquiring concepts.

Question:

Is coming to communicate with language essentially a matter of learning or inventing word-concept mappings?

‘What a strange phenomenon that a child can actually learn human language! That a child who knows nothing can start out and learn by a sure path this enormously complicated technique.’

Wittgenstein 1980: 2.24 [§128]

Yet Another Problem

Appendix: Grice/Tomasello (optional)

communication by language without mapping or training

social interaction

‘children acquire linguistic symbols as a kind of by-product of social interaction with adults’

Tomasello 2003, p. 90

Infants ‘begin to comprehend and use … linguistic symbols on the basis of their skills of social cognition and cultural learning’

Tomasello, Striano & Rochat 1999, p. 582

‘language is itself one type-albeit a very special type-of joint attentional skill’

‘the kind of rational activity which the use of language involves is a form of rational cooperation’

Grice 1989, p. 341

language creation

‘it is an error to suppose we have seen deeply into the heart of linguistic communication when we have noticed how society bends linguistic habits to a public norm.’

Davidson 1984 [1982]: 278

‘convention does not help explain what is basic to linguistic communication, though it may describe a usual, though contingent feature.’

Davidson 1984 [1982]: 280

‘An utterance has certain truth conditions only if the speaker intends it to be interpreted as having those truth conditions.’

Davidson 1990: 310

social interaction

language creation

Grice on meaning

'A speaker S non-naturally means something by an utterance x if and only if, for some hearer (or audience) H, S utters x intending:

(1) H to produce a particular response r, and

(2) H to recognise that S intends (1).

Grice 1957