Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Origins of Mind

Appendix: Theoretical Background

s.butterfill@warwick.ac.uk

the question

‘there are many separable systems of mental representations ... and thus many different kinds of knowledge. ... the task ... is to contribute to the enterprise of finding the distinct systems of mental representation and to understand their development and integration’\citep[p.\ 1522]{Hood:2000bf}.

(Hood et al 2000, p.\ 1522)

core knowledge

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 517)

‘core systems are largely innate, encapsulated, and unchanging, arising from phylogenetically old systems built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers.’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

representational format: iconic (Carey 2009)

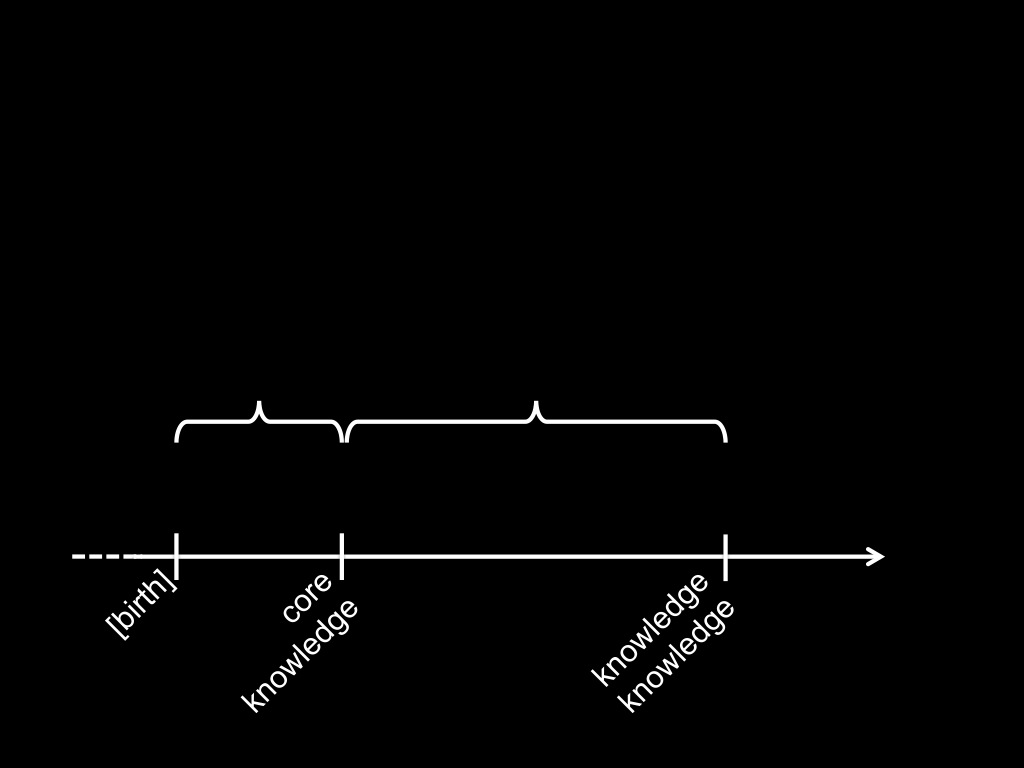

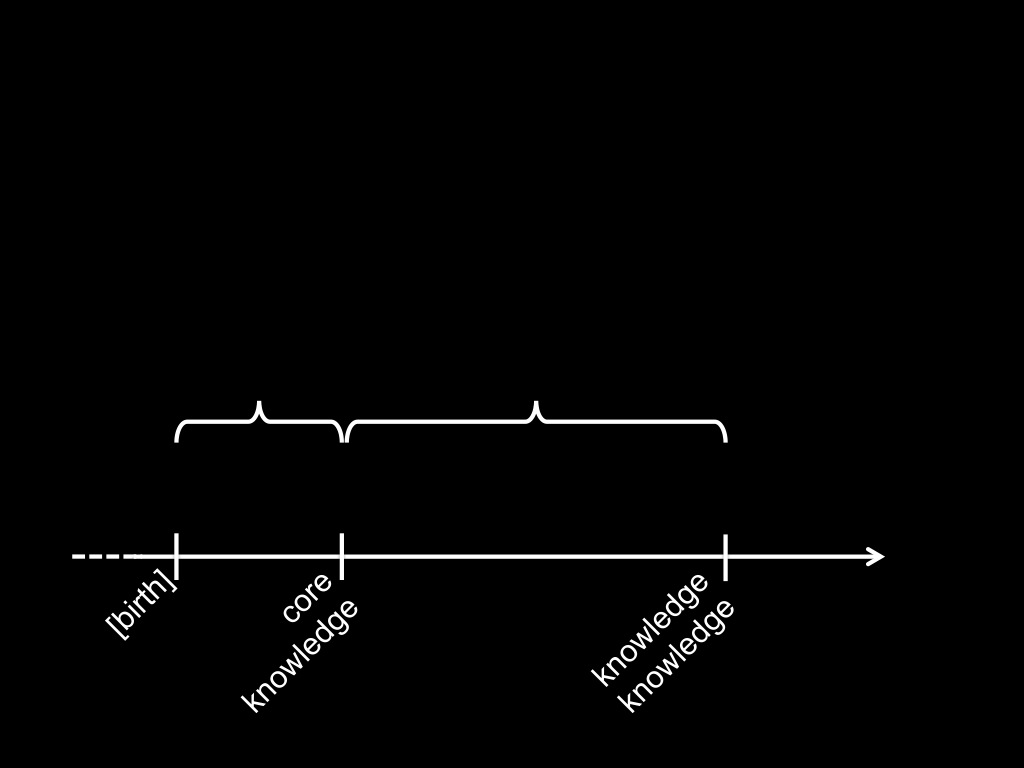

knowledge core knowledge

‘there is a paucity of … data to suggest that they are the only or the best way of carving up the processing,

‘and it seems doubtful that the often long lists of correlated attributes should come as a package’

Adolphs (2010 p. 759)

‘we wonder whether the dichotomous characteristics used to define the two-system models are … perfectly correlated …

[and] whether a hybrid system that combines characteristics from both systems could not be … viable’

Keren and Schul (2009, p. 537)

‘the process architecture of social cognition is still very much in need of a detailed theory’

Adolphs (2010 p. 759)

We have core knowledge of the principles of object perception.

two problems

- \item How does this explain the looking/searching discrepancy?

- \item Can appeal to core knowledge explain anything?

core system = module?

‘In Fodor’s (1983) terms, visual tracking and preferential looking each may depend on modular mechanisms.’

Spelke et al (1995, p. 137)

- domain specificity

modules deal with 'eccentric' bodies of knowledge

- limited accessibility

representations in modules are not usually inferentially integrated with knowledge

- information encapsulation

modules are unaffected by general knowledge or representations in other modules

For something to be informationally encapsulated is for its operation to be unaffected by the mere existence of general knowledge or representations stored in other modules (Fodor 1998b: 127) - innateness

roughly, the information and operations of a module not straightforwardly consequences of learning

core knowledge = modularity

We have core knowledge (= modular representations) of the principles of object perception.

two problems

- \item How does this explain the looking/searching discrepancy?

- \item Can appeal to core knowledge (/ modularity) explain anything?

- domain specificity

modules deal with 'eccentric' bodies of knowledge

- limited accessibility

representations in modules are not usually inferentially integrated with knowledge

- information encapsulation

modules are unaffected by general knowledge or representations in other modules

For something to be informationally encapsulated is for its operation to be unaffected by the mere existence of general knowledge or representations stored in other modules (Fodor 1998b: 127) - innateness

roughly, the information and operations of a module not straightforwardly consequences of learning

summary so far

core knowledge = modularity

We have core knowledge (= modular representations) of the principles of object perception.

two problems

- \item How does this explain the looking/searching discrepancy?

- \item Can appeal to core knowledge (/ modularity) explain anything?

The Beginning of the End

What is core knowledge? What are core systems (≈ modules)?

Why don’t I know the answers?

‘We hypothesize that uniquely human cognitive achievements build on systems that humans share with other animals: core systems that evolved before the emergence of our species.

‘The internal functioning of these systems depends on principles and processes that are distinctly non-intuitive.

‘Nevertheless, human intuitions about space, number, morality and other abstract concepts emerge from the use of symbols, especially language, to combine productively the representations that core systems deliver’

Spelke and Lee 2012, pp. 2784-5

‘All understanding of the speech of another involves radical interpretation’

Davidson 1973, p. 125

But what is core knowledge?

‘Just as humans are endowed with multiple, specialized perceptual systems, so we are endowed with multiple systems for representing and reasoning about entities of different kinds.’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 517)

‘core systems are

- largely innate,

- encapsulated, and

- unchanging,

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

core system vs module

‘core systems are

- largely innate,

- encapsulated, and

- unchanging,

- arising from phylogenetically old systems

- built upon the output of innate perceptual analyzers’

(Carey and Spelke 1996: 520)

Modules are ‘the psychological systems whose operations present the world to thought’; they ‘constitute a natural kind’; and there is ‘a cluster of properties that they have in common’

- innateness

- information encapsulation

- domain specificity

- limited accessibility

- ...

Why do we need a notion like core knowledge?

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

| syntax | [to follow] | [to follow] |

| number | [to follow] | [to follow] |

If this is what core knowledge is for, what features must core knowledge have?

limited accessibility to knowledge

maximum grip aperture

(source: Jeannerod 2009, figure 10.1)

| domain | evidence for knowledge in infancy | evidence against knowledge |

| colour | categories used in learning labels & functions | failure to use colour as a dimension in ‘same as’ judgements |

| physical objects | patterns of dishabituation and anticipatory looking | unreflected in planned action (may influence online control) |

| minds | reflected in anticipatory looking, communication, &c | not reflected in judgements about action, desire, ... |

| syntax | [to follow] | [to follow] |

| number | [to follow] | [to follow] |

next: syntax

Syntax / Innateness

core knowledge of

- physical objects

- [colour]

- mental states

- action

- number

- ...

- The turnip of shapely knowing isn't yet buttressed by death.

- *The buttressed turnip shapely knowing yet isn't of by death.

core knowledge of syntax is innate (?)

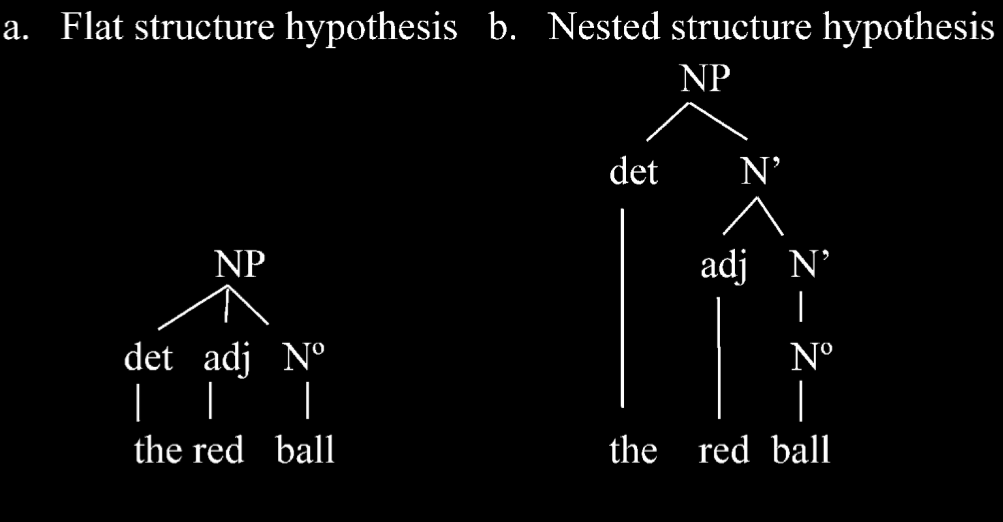

the red ball

‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’

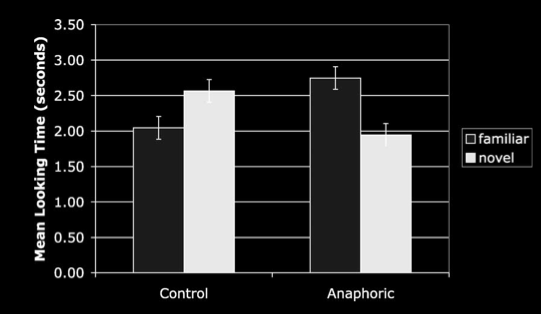

Lidz et al (2003)

- \item ‘red ball’ is a constituent on (b) but not on (a)

- \item anaphoric pronouns can only refer to constituents

- \item In the sentence ‘I’ll play with this red ball and you can play with that one.’, the word ‘one’ is an anaphoric prononun that refers to ‘red ball’ (not just ball). \citep{lidz:2003_what,lidz:2004_reaffirming}.

infants?

| Look, a yellow bottle! | control: What do you see now? test: Do you see another one? |

|

| [yellow bottle] | [yellow bottle] | [blue bottle] |

From 18 months of age or earlier, infants represent the syntax of noun phrases in much the way adults do.

But are these representations innate?

‘All understanding of the speech of another involves radical interpretation’

Davidson 1973, p. 125

Poverty of stimulus argument

-

\itemHuman infants acquire X.

-

\itemTo acquire X by data-driven learning you'd need this Crucial Evidence.

-

\itemBut infants lack this Crucial Evidence for X.

-

\itemSo human infants do not acquire X by data-driven learning.

-

\itemBut all acquisition is either data-driven or innately-primed learning.

-

\itemSo human infants acquire X by innately-primed learning .

compare Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 18

‘the APS [argument from the poverty of stimulus] still awaits even a single good supporting example’

Pullum & Scholz 2002, p. 47

What is innate in humans?

- What evidence is there?

- What does the evidence show is innate?

- Type: knowledge, core knowledge, modules, concepts, abilities, dispositions ...

- Content: e.g. universal grammar, principles of object perception, minimal theory of mind ...

so what?

Conclusion

- Adults have inaccessible, domain-specific representations concerning the syntax of natural languages.

- So do infants (from 18 months of age or earlier, well before they can use the syntax in production).

- These representations plausibly enable understanding and play a key role in the development of abilities to communicate with language.

- These representations are a paradigm case of core knowledge.

Syntax: Knowledge or Core Knowledge?

?

Are humans’ representations of syntax knowledge?

Humans can’t usually report any relevant facts about syntax.

Reply: maybe they know but don’t know they know.

‘It is of the essence of a belief [or knowledge] state that it be at the service of many distinct projects, and that its influence on any project be mediated by other beliefs.’

Evans 1981, p. 337

Humans’ representations concerning syntax are tied to a single project.

(One requirement for this is that they exhibit limited accessibility.)

aside

‘At the level of output, one who possesses the tacit knowledge that p is disposed to do and think some of the things which one who had the ordinary belief that p would be inclined to do an think (given the same desires).

‘At the level of input, one who possesses the state of tacit knowledge that p will very probably have acquired that state as the result of exposure to usage which supports of confirms … the proposition that p, and hence in circumstances which might well induce in a rational person the ordinary belief that p.’

(Evans 1981, p. 336)

The generality constraint applies to knowledge knowledge but not to tacit knowledge.

Humans’ representations of syntax aren’t knowledge because they exhibit limited accessbility and are tied to a single project.

?

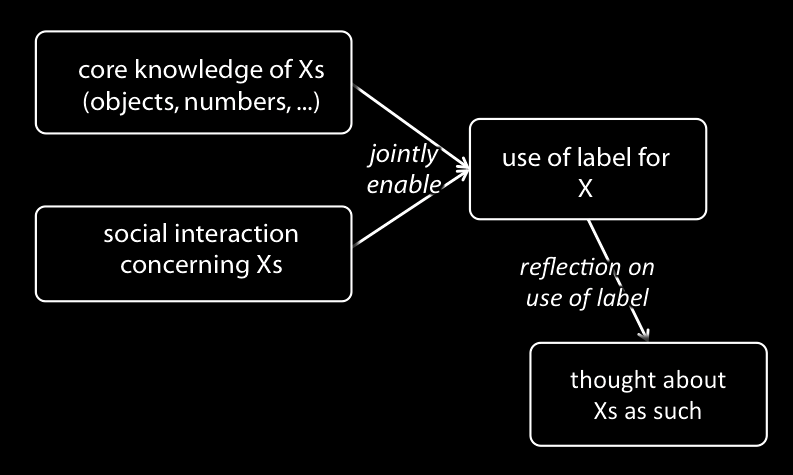

What is the relation between core knowledge and knowledge knowledge?

The Wrong View

Modules ‘provide an automatic starting engine for encyclopaedic knowledge’

Leslie 1988: 194

‘The module … automatically provides a conceptual identification of its input for central thought … in exactly the right format for inferential processes’

Leslie 1988: 193-4

But: inaccessibility

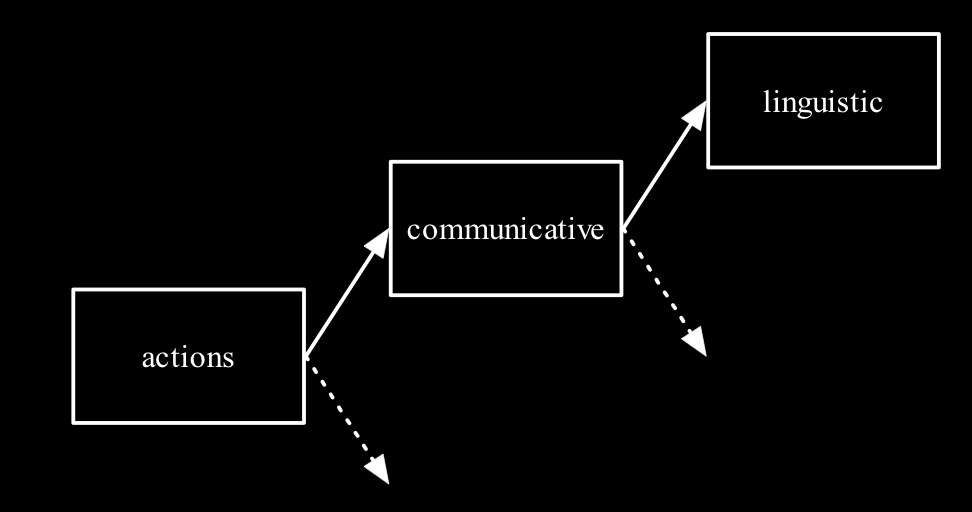

development as rediscovery

the question

indirect approach

‘modern philosophers … have no theory of thought to speak of. I do think this is appalling; how can you seriously hope for a good account of belief if you have no account of belief fixation?’

(Fodor 1987: 147)

‘Thinking is computation’

(Fodor 1998: 9)

three points of comparison

- performance (patterns of success and failure)

- hardware

- program (symbols and operations vs. knowledge states and inferences)

thinking isn’t computation … Fodor’s own argument

1. Computational processes are not sensitive to context-dependent relations among representations.

2. Thinking sometimes involves being sensitive to context-dependent relations among representations as such.

(e.g. the relation … is adequate evidence for me to accept that … )

3. Therefore, thinking isn’t computation.

‘the Computational Theory is probably true at most of only the mind’s modular parts. … a cognitive science that provides some insight into the part of the mind that isn’t modular may well have to be different, root and branch’

(Fodor 2000: 99)

1. Computational processes are not sensitive to context-dependent relations among representations.

2. Thinking sometimes involves being sensitive to context-dependent relations among representations as such.

3. Therefore, thinking isn’t computation.

If a process is not sensitive to context-dependent relations, it will exhibit:

- information encapsulation;

- limited accessibility; and

- domain specificity.

(Butterfill 2007)

computation is the real essence of core knowledge (/modularity)

‘there is a paucity of … data to suggest that they are the only or the best way of carving up the processing,

‘and it seems doubtful that the often long lists of correlated attributes should come as a package’

Adolphs (2010 p. 759)

‘we wonder whether the dichotomous characteristics used to define the two-system models are … perfectly correlated …

[and] whether a hybrid system that combines characteristics from both systems could not be … viable’

Keren and Schul (2009, p. 537)

‘the process architecture of social cognition is still very much in need of a detailed theory’

Adolphs (2010 p. 759)

Fodor

Q: What is thinking?

A: Computation

Awkward Problem: Fodor’s Computational Theory only works for modules

Fodor

Q: What is modularity?

A: Computation

Useful Consequence: Fodor’s Computational Theory describes a process like thinking

core knowledge = modularity

We have core knowledge (= modular representations) of the principles of object perception.

two problems

- How does this explain the looking/searching discrepancy?

- Can appeal to core knowledge (/ modularity) explain anything?

questions

1. How do humans come to meet the three requirements on knowledge of objects?

2a. Given that the simple view is wrong, what is the relation between the principles of object perception and infants’ competence in segmenting objects, object permanence and tracking causal interactions?

2b. The principles of object perception result in ‘expectations’ in infants. What is the nature of these expectations?

3. What is the relation between adults’ and infants’ abilities concerning physical objects and their causal interactions?