Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

Creativity

recap

Assumption:

If someone can communicate with language, she can think.

Consequence:

Acquiring language cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Question:

How could someone begin to acquire words without being able to think?

Answer:

By being trained to utter a particular word in response to certain simulations!

Observation:

There is a gap between what training achieves (use) and what language acquisition requires (understanding).

Now:

How do children actually acquire language?

homesigns

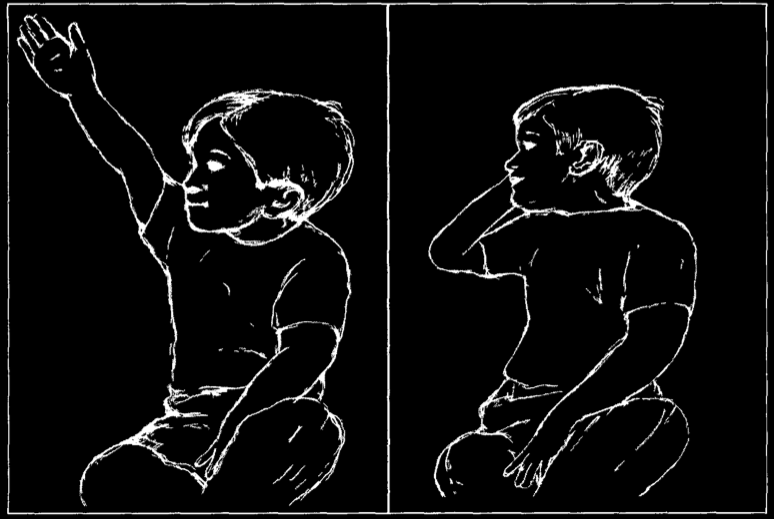

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 1)

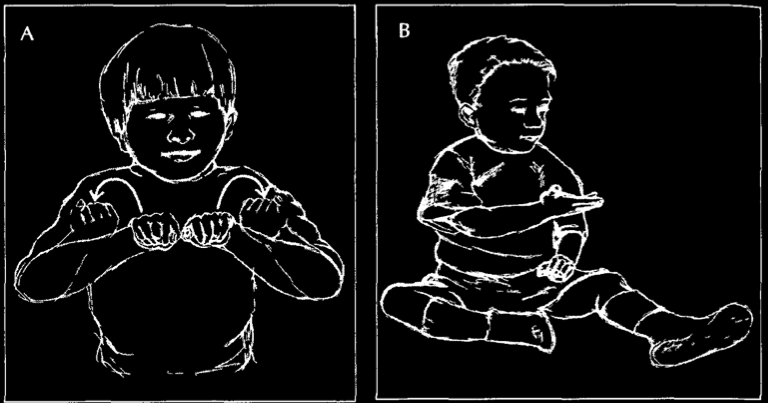

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 2)

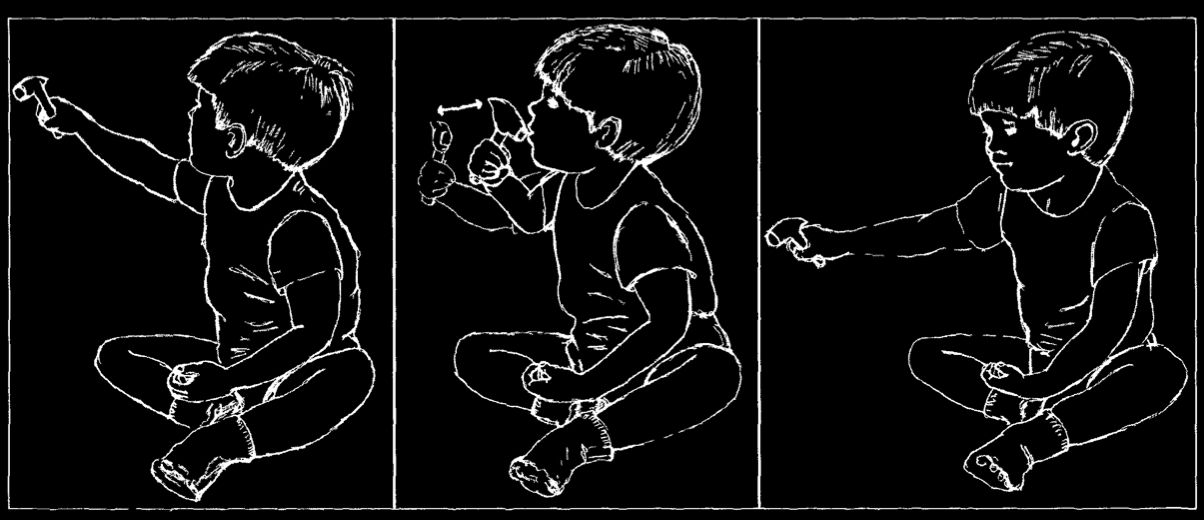

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 11)

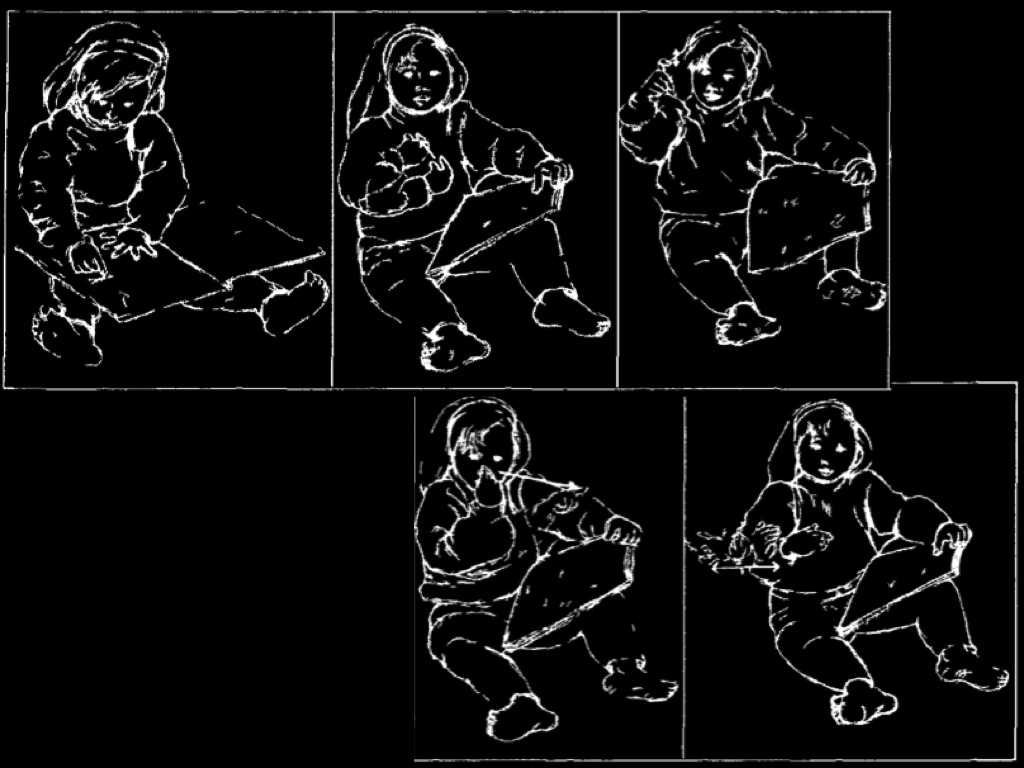

Goldin-Meadow (2003, figure 22)

Gesture forms are:

- stable

- arbitrary

- systematic

Gesture forms are used:

- with different forces (to ask questions, make comments, request things, ...)

- to talk about past, future and hypothetical things

- to tell stories

- to communicate with oneself

- to talk about gestures (metalanguage)

Goldin-Meadow 2002

Children can create their own first languages.

recap

Assumption:

If someone can communicate with language, she can think.

Consequence:

Acquiring language cannot involve thinking at the outset.

Question:

How could someone begin to acquire create words without being able to think?

Answer:

By being trained to utter a particular word in response to certain simulations!

Observation:

There is a gap between what training achieves (use) and what language acquisition requires (understanding).

Now:

How do children actually acquire language?

aside

- If someone can think, she must be capable of having a false belief.

- To be capable of having a false belief it is necessary to understand the possibility of false belief.

- Understanding the possibility of false belief entails being able to communicate by language.

Conclusion:

If someone can think, she can communicate with language.

‘Intentional action cannot emerge before belief and desire, for an intentional action is one explained by beliefs and desires that caused it.’

Davidson 1999, p. 10