Press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (no equivalent if you don't have a keyboard)

Press m or double tap to see a menu of slides

How Do Infants Model Actions?

What model of action underpins six- or twelve-month-old infants’ abilities to track the goals of actions?

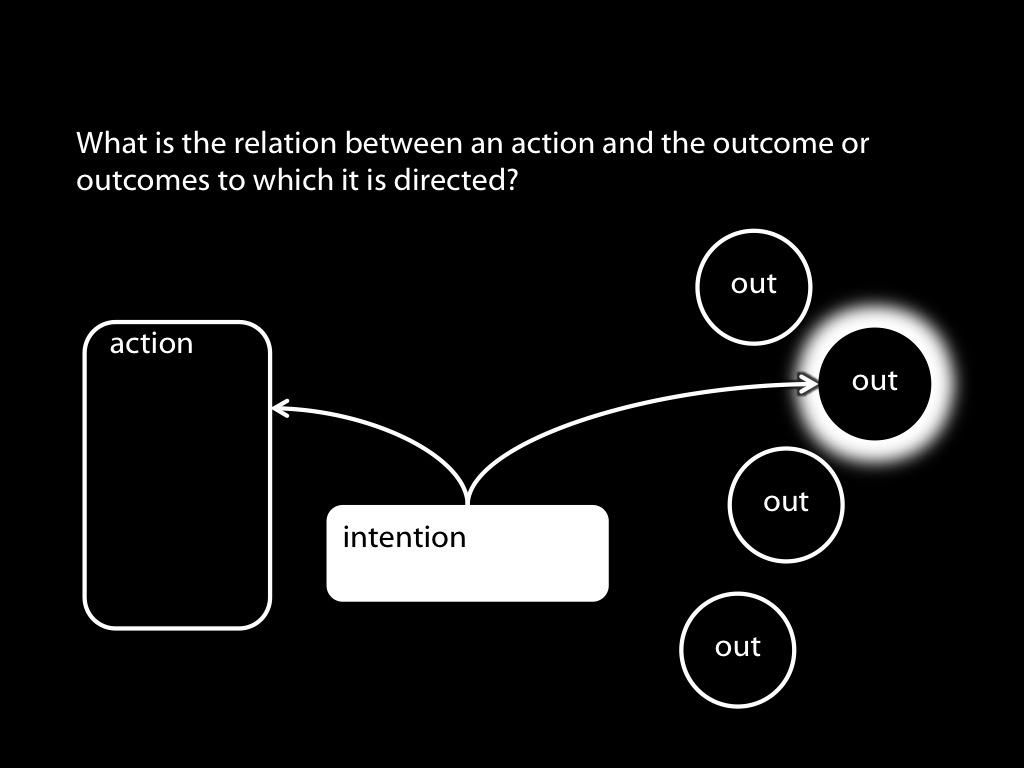

What is a model of action?

Does infants’ model involve intentions?

Yes: ‘in perceiving one object as having the intention of affecting another, the infant attributes to the object [...] intentions’

Premack 1990: 14

No: ‘by taking the intentional stance the infant can come to represent the agent’s action as intentional without actually attributing a mental representation of the future goal state’

Gergely et al 1995, p. 188

Sort of:‘to the extent that young infants are limited [...], their understanding of intentions would be quite different from the mature concept of intentions’

Woodward et al 2001, p. 168